Judith Wright knows what it takes to be a successful artist: her great-great-grandmother showed her the way.

“Never showy, she is a master of devastating understatement.”

Tony Hughes-d’Aeth, Professor of Literature, University of Western Australia

Judith Wright is known in Australia as an activist poet. In today’s poem, written in 1955, she recounts the story of her own legendary great-great-grandmother, a woman with an artistic calling but who lived in a Victorian world that expected her to be a mother above all else. Wright was to suffer the sting of similar sexist attitudes herself, intentional or otherwise, when she was called a ‘shrew’ by a fellow poet in a published review of her writing, so she knew what it was like to have to swim against the tide when it came to the pursuit of her own dreams. Request to a Year, as well as telling a wonderfully dramatic action-packed story passed down to Wright through generations of daughters in her own family tree, celebrates the achievement of a woman who had to overcome prejudice, the weight of social expectation, and her own motherly instincts in order to get one shot at doing what she really loved – making art:

If the year is meditating a suitable gift, I should like it to be the attitude of my great-great-grandmother, legendary devotee of the arts. Who, having had eight children And little opportunity for painting pictures, Sat one day on a high rock Beside a river in Switzerland And from a difficult distance viewed Her second son, balanced on a small ice-floe, Drift down the current towards a waterfall That struck rock bottom eighty feet below, While her second daughter, impeded, No doubt, by the petticoats of the day, Stretched out a last-hope alpenstock (which luckily caught him on his way). Nothing, it was evident, could be done; And with the artist’s isolating eye My great-great-grandmother hastily sketched the scene. The sketch survives to prove the story by. Year, if you have no Mother’s Day present planned; Reach back and bring me the firmness of her hand.

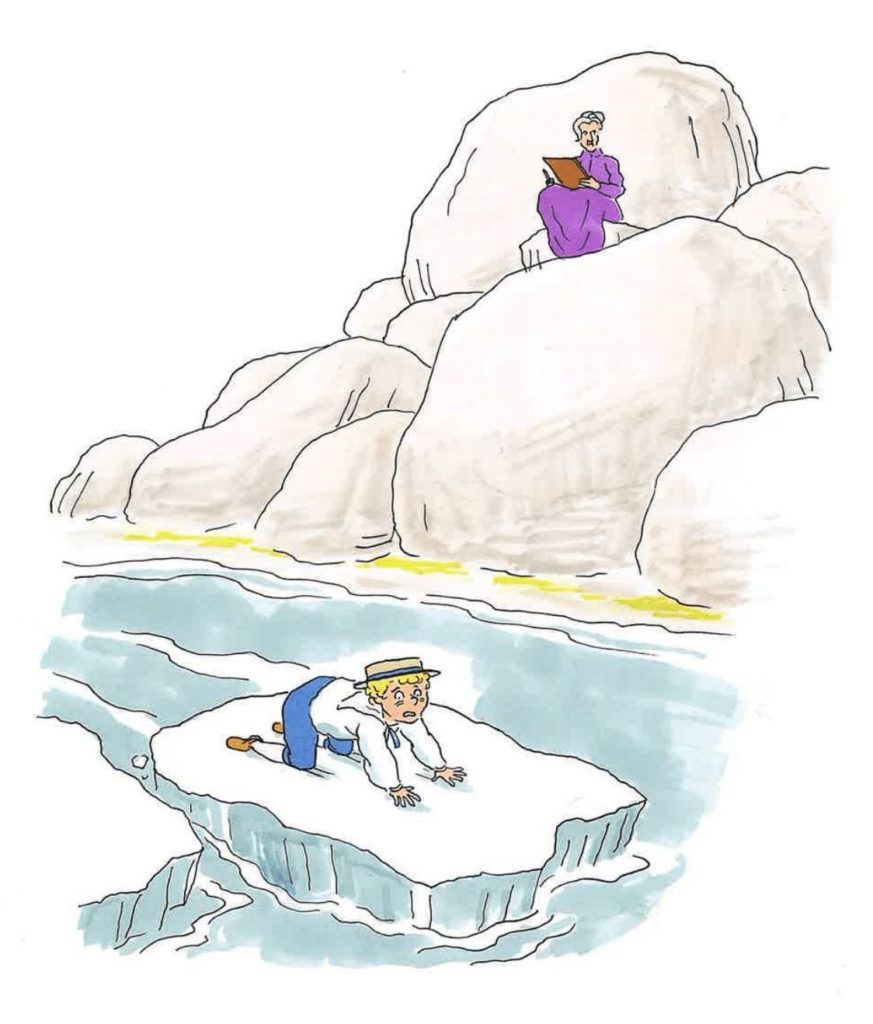

The central achievement of this poem is how it reverses our expectations of heroism and who, precisely, can act like a hero – and it does this not once, but twice. Firstly, the poem presents a piece of action so conventional it’s been a trope since 1920. While walking high in the Swiss mountains, the second son of the speaker’s great-great-grandmother decides to casually stroll out onto a frozen river. Of course, things go horribly wrong when the river smashes up the ice and, stranded on a floe, he’s whisked away by the strong current. Fortunately, the intrepid boy’s companion has the speed of thought to thrust out an alpenstock (a long walking staff) which the stranded walker grasps… and is hauled to safety at the last-hope moment. While all this drama is presented in an understated way (the successful rescue is only mentioned in brackets/parentheses, as if it’s an afterthought) it still shouldn’t escape anyone’s notice that the quick-thinking hero was… drum roll… a GIRL!!! Placing the boy in a position of jeopardy from which he needs to be saved and casting his sister as his gallant rescuer – and then understating it! – inverts the typical damsel-in-distress narrative trope years before Disney thought of doing the same thing.

While it may seem incidental to the action, the mention of the girl’s petticoats is an important detail, as clothing symbolises social restrictions limiting the roles women could play during the nineteenth century. Petticoats are surprisingly complicated garments, sometimes consisting of several layers, made of billowing fabrics for warmth, fashion, and modesty. Needless to say, they are not the most practical items of clothing to wear when conducting a rescue. If you’ve seen the recent Wonder Woman film, you might remember the funny scene in a London shop where Diana was trying on various items of clothing so she could blend in to her modern surroundings effectively. Each time she tries on a new outfit, she rips it by performing a fighting move: the restrictive clothes are simply not suitable for the active role she’s supposed to play in the story. The same effect is created in this poem, where Wright reminds us that the daughter was acting not only against social expectations of a woman’s role, but against day-to-day obstacles that discouraged (impeded) girls from acting heroically.

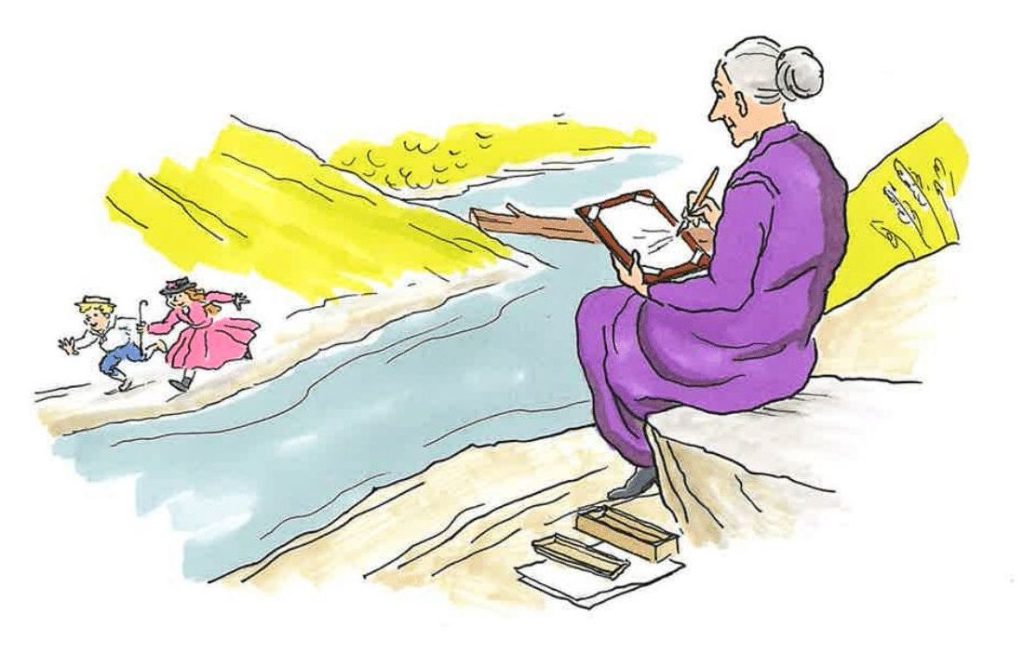

However, the way the action is presented through the great-great-grandmother’s distant perspective (Sat one day on a high rock) asks us to reconsider not only our preconceptions about who can be a hero, but what is allowed to constitute heroic action. As noted, the rescue itself is not the focus of the poem; it’s the calm, stoic behaviour of the grandmother that the speaker remembers and the firmness of her hand that she asks to be bestowed with. Instead of panicking, screaming, or rushing off uselessly down the mountain, this lady simply takes her pencil in hand and hastily sketched the scene. Emotional stoicism is a trope normally associated with the strong, silent male archetype; in women the same trait can be misrepresented as cold-heartedness. The only word that hints at any emotional stress is hastily – and it’s strongly implied that her sole worry was capturing the scene in the instant rather than concern over her son’s welfare. At the time, she could not possibly have known whether her own child would live or die!

The poem offers us the opportunity to test ourselves when we read this line: think back to your own response when, while her son was being whisked towards a fatal fall, against her motherly instincts, she simply recorded the scene for posterity. Wright is purposefully baiting her readers, whose reactions are likely to fall into one of two broad categories. Did you think: ‘yep, well, you’re too far away to do anything anyway, why not seize the moment you’ve been waiting for all your life?’ Or was your reaction something along the lines of: ‘what are you doing, you crazy lady? Your kids are in danger – just get down there and do something!’ Do you see a logical choice or a cold-hearted monster? It’s clear where the speaker’s, and therefore Wright’s, sympathies lie when she informs us: Nothing, it was evident, could be done. Perspective is important in both senses of the word: not only are we shown the scene from the speaker’s great-great-grandmother’s distant perspective (difficult distance, high rock) but we are also being asked to take a logical view of her actions rather than give way to bias or hysterics.

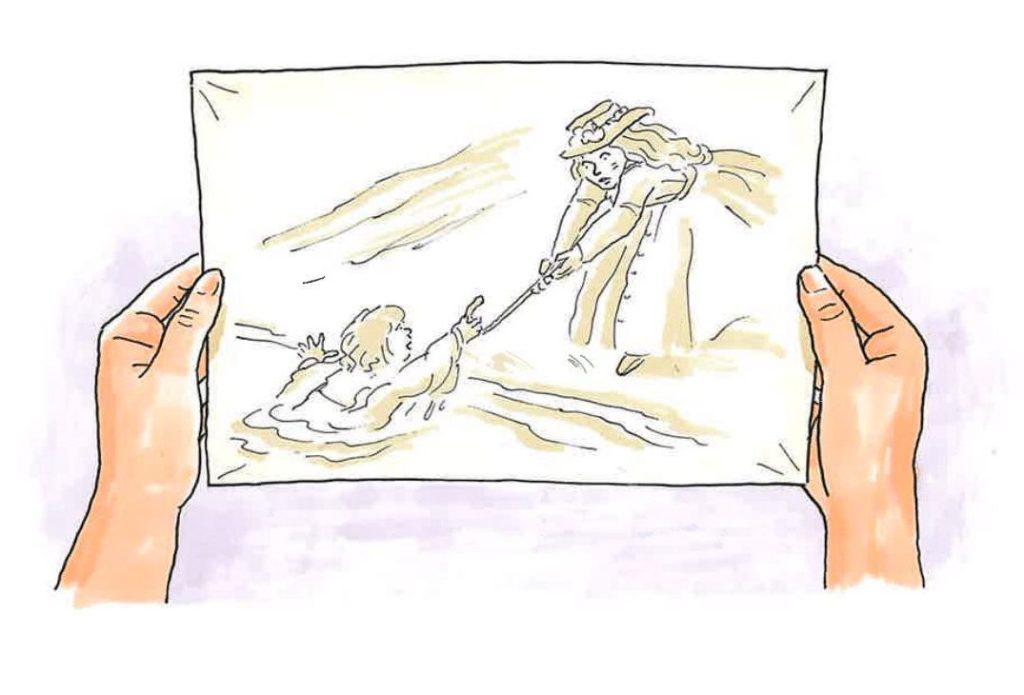

The success of her great-great-grandmother’s endeavour, the justification for her action, is in the final line of verse five, which simply reads: The sketch survives to prove the story by. While we’re used to the poem’s understatement by now, we should still recognise the sketch as the poem’s most important symbol, representing her great-great-grandmother’s determination and proof of her latent talent that flourished belatedly. The fact that the sketch still exists generations later implies the value the drawing must have held for her family: it was seen as worthy of preservation and is now inspiring the writer to follow her own artistic pursuit. This sentence is enhanced by a lovely combination of sibilance (sketch, survives, story) and assonance (to prove, story and survives, by) and bracketed by full stops so it sits on a line of its own – the only sentence in the poem to do this. By contrast, verses two to four are all one long sentence running from line to line, and even skipping from verse to verse, with barely even a comma to disrupt the flow. This obvious enjambment creates a variety of effects, including mimicking the rushing river whisking her son towards that precipice, and summoning other aspects of the fast-paced drama unfolding all those years ago, such as the quick actions of the rescuer and the hasty scribblings of the woman recording the scene. Enjambment also enhances the relationship between the poem’s speaker, her great-great-grandmother, and all the generations of daughters in between, a link otherwise embodied by the sketch that was passed down from hand to hand – a link that will presumably extend into the future when the speaker passes it, along with the story of how it was made, to her own daughter.

At the start of her recount, Wright informs us that her great-great-grandmother was a mother eight times over (having had eight children) and the fact that the two children involved in the river rescue are her second son and her second daughter seems like a pointed repetition. The implication is that motherhood is just as much an impediment to artistic endeavour and self-expression as those ridiculous petticoats. It is only through the willingness to give up motherhood that one’s inner desires, whatever they may be, can be pursued. A mother has to be willing to put her children to one side – more, symbolically sacrifice her child by doing nothing when he’s in danger – if she wants to transcend this label and do what matters to her deep down. And before you judge her too harshly for this ‘heartless betrayal,’ consider how – almost a quarter of the way into the twenty-first century – many women still have to battle a widespread expectation that they should be childminders first, putting their own hopes, dreams, and careers on hold when society expects them to stay at home looking after the kids. The poem frequently draws from a lexical field of words suggesting ‘difficulty,’ including difficult, impeded, and balancing – all words which connote having to overcome obstacles and ingrained social opposition if one wants to pursue an alternative path through life. The poem’s speaker, representing Judith Wright herself, is not ignorant of any of these subtleties. Presumably, as she’s thinking about a Mother’s Day present, she’s a mother herself; therefore, when she asks to inherit her grandmother’s firmness of hand, she understands that ‘firmness’ is not just a physical strength but an emotional quality too. She recognises that pursuing art can be lonely and that others won’t always like or approve of the choices she might make. This idea is conveyed through the line and with the artist’s isolating eye in verse five as, at the crucial moment, the speaker’s great-great-grandmother transforms into the artist she was always meant to be (there’s a progression from devotee of the arts to artist between verses one and five). The word isolating has layers of meaning above and beyond loneliness: it’s like her gaze snaps into the focused concentration of an artist at just the right time, arrowing onto the important details of the scene; simultaneously, the word reinforces the importance of perspective in the manner of artists keeping an objective distance between themselves and their subject matter, and the deliberate way this particular artist cuts herself off from her family, even as one of them is in desperate peril. The carpe diem moment is heightened by a sudden, keen assonance (isolating eye) which draws extra attention to the importance of this word in the poem.

In other ways too, Wright suggests mastering an art form is a difficult endeavour, an idea implied through the form of her own poem as she struggles to get her poetry ‘right.’ To begin with, the poem deliberately has no discernible rhythm or rhyme. It’s written in stanzas of four lines each called quatrains… but that’s really it. The poem itself strives towards form, towards being a better poem, but it’s only in later verses that this ambition is realised. See how the poetic features of the poem become more pronounced by looking at stanza one placed next to stanza four below. Rhythm and rhyme assert themselves more confidently in the later verses, as if poetic (or artistic) skill is something to be worked towards, strived for, rather than something one simply possesses without effort:

If the yēar/ is mēd/ itating a sūit/ able gīft,/ I should līke/ it to bē/ the /āttitude …my grēat/-grēat-/ /grāndmother, /lēgendary devotēe/ of the ārts./

While her sēc/ ond dāught/ er, impēd/ ed, no dōubt,/ by the pētt/ icoats ōf/ the dāy,/ Stretched oūt/ a lāst/-hope āl/ penstōck/ (which lūck/ ily lāt/ er cāught/ him ōn/ his wāy)./

In stanza one on the left, the accented beats are irregular, following no pattern from line to line, and none of the end-words rhyme at all. Compare this to stanza four on the right, where the rhythm eventually resolves into the recognisable ‘de-dum, de-dum’ of iambic beats in the last two lines and rhymes appear in the pattern of ABCB. Later, these features have even more clarity (look at the ABAB rhyme scheme of stanza five – done/scene are half-rhymes – and how the poem ends with a satisfying rhyming couplet: planned/hand) implying that it is through the retelling of her grandmother’s story, and the internalisation of her strength, that the poet truly begins to master her craft. The very form of the poem is a tribute to her great-great-grandmother’s journey.

The same is true for other poetic embellishments to the story. To begin with, the poem’s speaker retreats behind a formal mode of address, characterised by an excessive dental consonance using the letters D and T; If the year is meditating a suitable gift, I should like it to be the attitude of my great-great-grandmother, legendary devotee of the arts. You should put on a posh voice and read this verse out loud to hear the effect of all these enunciated letters formed by touching the tongue to the back of the upper teeth. The same goes for her use of the letter P in the second verse: opportunity for painting pictures. All these clipped sounds give her voice a cool, detached tone, as if she’s holding everything at arm’s length, neither internalising her ancestor’s determination yet, nor being sure of her own storytelling skills. Perhaps this over-enunciation evokes the reserved, Victorian personality of a woman who had to bury her true desires behind family responsibilities? The prim tone is an effective precursor to the idea that an artist requires a necessary objective distance from her subject matter, so these sounds help prepare the reader for this idea when it comes. Once she gets into the story, though, the speaker relaxes into her role as entertainer and the drama is enlivened through the way she uses language. We’ve already mentioned her use of enjambment to whisk us smoothly through the action. The impressive alpine scenery is sketched incredibly economically, a few words and phrases here and there (such as high rock, river in Switzerland, waterfall… eighty feet below…) enough to evoke images of high mountains, craggy valleys and crystal clear, freezing winter waters. Once the walking group reach the river, plenty of sibilance creates an auditory simulation of the rushing water; listen to all those S sounds surging and swirling through her second son balanced on a small ice floe. Like chunks of ice and rock bobbing along the river’s course, Wright studs the following couple of verses with a whole gamut of hard, emphatic alliterations that bring out the danger of the scene: difficult distance; drift down; struck rock are three instances from the third verse alone – can you find any more examples from verse three onwards?

The poem ends with a reiteration of the request to a year that the speaker made at the start of the poem, so that the beginning and end are connected in a loop composition that reinforces the link between herself and her great-great-grandmother. Finally, she directly addresses time itself, personifying the Year as an ally who can reach back and retrieve the necessary ingredient for her own success: her great-great-grandmother’s firmness of hand, a quality that encompasses not only artistic skill, but level-headed calm, strength of mind, and willingness to make the hard choices, no matter how others might perceive her. All the things we’ve already discussed – steady rhythm, full-rhyme, confident alliteration (present planned, reach back and bring) – are masterfully displayed at this moment, leaving us in no doubt that Wright’s speaker will come into her own artistic talent over the natural course of time.

That is if, on reading the exquisite final couplet, you think she hasn’t already.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Woman to Child by Judith Wright

In this famous poem Judith Wright again explores the link between generations in a family, this time through a mother speaking directly to her child about the mystery of birth.

- Sestina by Elizabeth Bishop

In this intricately constructed poem (a sestina is a poem of six verses plus a half verse; each verse has six lines; and the last word of each line repeats itself in a different position in all six verses!), Bishop thinks back to her relationship with her grandmother in a wonderfully ambiguous and moving way.

- Dedication for a Plot of Ground by William Carlos Williams

The poet was mixed English and Puerto Rican ancestry, and this poem pays tribute to his English grandmother Emily Dickinson Wellcome. Just take a look at all the incredible adventures she survived! Williams stands by the little plot of land she bought and defended until her last breath.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Request to a Year at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining how different types of alliteration and consonance are made in poetry.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Judith Wright’s poem? What is your opinion of the poet’s great-great-grandmother’s actions? Do you agree that sacrifice is necessary if one wants to achieve a dream or pursue an obsession? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

i dont like poems, especially this one. Very boring and lacking of content.

i disagree

i do like poems, especially this one. Very not boring and not lacking of content.

I disagree. I don’t like poems, especially this one. Very boring and lacking content.

Agree with the Disagreement, very not not boring and not not lacking content

Agree with the Disagreement, very not not boring and not not lacking content

I LOVE IT, THANK YOU SO MUCH IT HELP ME PASS MY IGCSE EXAM!!!!

Thank you Jose – I hope you aced the exam!