Fleur Adcock reminds us that, in the final reckoning, we’re all winners; we just need to remember to appreciate it.

“Such joy and mischief… an enjoyably light approach to potentially heavy subjects…”

Emma Neale, Academy of New Zealand Literature.

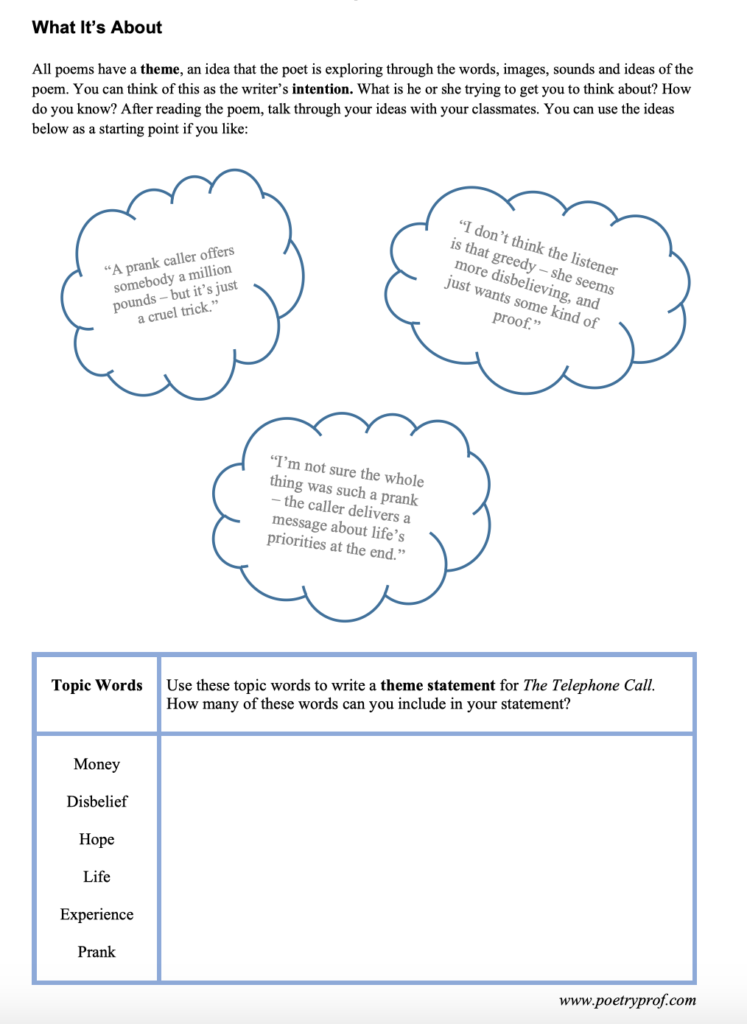

As the mysterious lottery rep in today’s poem says: Nearly everyone’s bought a ticket in some lottery or another, once at least, whether the prize is a million pounds in a national lottery, a dream house, or just a silly teddy bear at a charity raffle. And, if you’re lucky enough, you may even have had your ticket pulled out of the tombola once or twice. But what if, one day, you won the big one – the accumulator bet, the rollover multi-million jackpot, the Ultra-super Global Special Top Prize? That’s exactly what happens in Fleur Adcock’s The Telephone Call. An ordinary person is, presumably, just about to sit down for some dinner when the phone rings and, on picking up, she is told she’s won the lottery. But it’s not long before the conversation starts to take a very strange turn and we discover things are not all they seem to be:

They asked me, ‘Are you sitting down? Right? This is Universal Lotteries’, they said. ‘You’ve won the top prize, the Ultra-super Global Special. What would you do with a million pounds? Or, actually, with more than a million – not that it makes a lot of difference once you’re a millionaire.’ And they laughed. ‘Are you OK?’ they asked – ‘Still there? Come on, now, tell us, how does it feel?’ I said, ‘I just… can’t believe it!’ They said, ‘That’s what they all say. What else? Go on, tell us about it.’ I said, ‘I feel the top of my head has floated off, out through the window, revolving like a flying saucer.’ ‘That’s unusual’ they said. ‘Go on.’ I said ‘I’m finding it hard to talk. My throat’s gone dry, my nose is tingling. I think I’m going to sneeze – or cry. ‘That’s right’ they said, ‘don’t be ashamed of giving way to your emotions. It isn’t every day you hear you’re going to get a million pounds. Relax, now, have a little cry, We’ll give you a moment…’ ‘Hang on!’ I said. I haven’t bought a lottery ticket for years and years. And what did you say the company’s called?’ They laughed again. ‘Not to worry about a ticket. We’re Universal. We operate A retrospective Chances Module. Nearly everyone’s bought a ticket in some lottery or another, once at least. We buy up the files, feed the names into our computer, and see who the lucky person is.’ ‘Well, that’s incredible’ I said. ‘It’s marvellous. I still can’t quite… I’ll believe it when I see the cheque.’ ‘Oh,’ they said, ‘there’s no cheque.’ ‘But the money?’ ‘We don’t deal in money. Experiences are what we deal in. You’ve had a great experience, right? Exciting? Something you’ll remember? That’s your prize. So congratulations from all of us at Universal. Have a nice day!’ And the line went dead.

The telephone is something of a motif in Fleur Adcock’s poems. In For Heidi with Blue Hair, a phone call connects a strict headmaster, who sends Heidi home from school for dying her hair an unnatural colour, and Heidi’s angry father who argues the case for freedom of expression. It’s easy to think how a telephone can symbolise the idea of communication through the connection between two people who might be physically far apart. But in both Heidi and our poem today, the telephone actually reveals how two people can be connected yet disconnected, talk without understanding. In The Telephone Call, the power dynamic is all wrong: the call arrives unexpectedly, the person who picks up the phone is not ready or prepared for the news she receives, and the caller holds all the power because he knows what the punchline is going to be.

Initially I thought The Telephone Call was a straightforward take-down of consumer culture, the way we tend to measure the success of life in terms of how much money we happen to have. And in a big way it is. Adcock’s poem frames the whole of life as one big – Universal – lottery: some people ‘win’ and get to live as filthy rich millionaires. The rest of us look on, perhaps with a touch of envy, wondering what life would be like if we could enjoy some of that wealth. The company rep’s description of life if you’re rich touches on this theme as well. He says, with a condescending laugh: ‘not that it makes a lot of difference once you’re a millionaire.’ In this scenario, life is a zero-sum-game. Some people are winners and everyone else, by definition, is a loser. It’s a binary trap – but one that even those of us who say we don’t care about money fall into occasionally, especially when offered the chance to join the ‘winning’ side. The poem’s dialogue form is so recognisable that it encourages us to put ourselves in the ‘winning’ position, and reading it prompted me to wonder how I might act if I am ever told I will receive such an unexpected windfall. However, if you follow the poem through to its end, Adcock reveals that, if you think about life from the point of view of experiences rather than money, we’re all winners – anybody reading these words is lucky enough to have already won the metaphorical prize of life. The poem’s unusual premise – the offering up of a million before snatching it away at the last moment – simply reminds us to keep a healthy perspective when it comes to money matters. Plenty of exciting things happen every day; winning the lottery is just an extreme and unlikely example.

The word-for-word transcription of the dialogue between the representative of a mysterious lottery company and the supposed winner of the lottery is the most unique aspect of the poem, even including speech marks and speech tags (I said… they said… and so on) to help the reader keep track of who is speaking when. Unlike dialogues written in novels or stories, Adcock doesn’t begin a new line when the voice changes from one character to the other, so occasionally things might get a little confusing. On top of this, Adcock marks some lines with frequent punctuation while letting other lines run one into another without punctuation or pause, using a technique called enjambment. Line seven running into eight, not that it makes much difference once you’re a millionaire, features a perfect example of this technique. I shouldn’t worry if you find it a little hard to follow on first reading: on one hand, each of the two characters has their own recognisable voice that you’ll get used to pretty quickly. The lottery rep uses a kind of ‘telephone marketing’ language, including words from this lexical field such as top prize, Ultra-super Global Special and our computer while the flabbergasted ‘winner’ reacts in a predictably astonished way: ‘I just… I can’t believe it.’ On the other hand, any confusion or disorientation you might feel on first read is a great way of putting yourself in the position of the person on the other end of the line, snapped out of a presumably ordinary day with news that will completely change her life.

The representation of the salesperson as a formless, disembodied voice on the other end of the phone is pointed. He comes across as a mean-spirited huckster, even before the big reveal at the end. To begin with he employs copious hyperbole, which is the deliberate exaggeration of language, to overwhelm his listener and elicit the strong emotional reaction he’s presumably fishing for. Words like special, ultra-super, more than a million and top prize are prime examples of this unsubtle hyperbole. Apart from this though, his voice can be heartless and even cold: consonance and alliteration are employed as embellishments, making him sound distant and occasionally cruel. When he first speaks his tone is prim and proper, accentuated by dental T sounds (‘Are you sitting down? Right? This is Universal Lotteries’) and the delivery of his startling news is emphasised by strong plosive P and B: ‘You’ve won the top prize, the Ultra-super Global Special.’ Of course, cordiality and enthusiasm is all part of his act so, once he’s got her snared in his trap, Adcock blends in some harsher gutturals (made with letters G and C) to give his words an unpleasant undertone; for example, ‘You’re going to get a million pounds. Relax, now, have a little cry, we’ll give you a moment…’ There’s more than a touch of meaningless jargon to some of the rep’s language (I’m looking at you, retrospective Chances Module) and he also employs one or two cliches, such as It’s not every day… and Have a nice day! as if he’s not particularly invested in what he has to say. The language he uses to describe the processes of his company – particularly his choice of verbs: bought, buy, feed, deal, operate – and the way good fortune seems to rely on the whims of a computer are indicative of the technological, transactional nature of life in the modern world. Citizens of capitalist societies, certainly, are conditioned to consider themselves ‘consumers’ first and ‘human beings’ second.

Initially, he dominates the conversation and the recipient of the call doesn’t get to speak until the second verse; even then, the balance of dialogue is always weighted towards the caller. He has all the power in this interaction; he’s the one who phones out of nowhere, sets the agenda of the call, and controls the direction of the conversation. As the poem unfolds, right up until the twist in the final stanza, the voice takes on a more pressing tone. If the whole thing really is just a cruel hoax, he milks it for all it’s worth by repeatedly asking short, sharp questions one after another, not giving his listener a moment to find her equilibrium. The way he wants to know how she feels all the time is sinister, almost vampiric, as if he’s feeding on her emotional reaction. He exhorts her to cry, says don’t be afraid of giving in to your emotions, and repeats tell us, as in this example:

‘Are you OK?’ they asked – ‘Still there? Come on, now, tell us, how does it feel?’

Some of his lines are very choppy, fragmented with frequent punctuation making it seem like he’s slowly coaxing her in a sinister way. His nagging insistence is created using the imperative tense whereby the verb is placed at the start of the phrase (Come on… don’t be… tell us… and so on). It suggests something macabre in his intentions; he’s forcing her to interact and relishing her discombobulation when she can’t find the right words. At other points, he’s a little condescending of her, laughing at her twice, and a dismissive sneer occasionally slips through his polished patter, such as when he says: have a little cry. Through the unpleasant characterisation of the caller, the poem implies that life can be ugly and dog-eat-dog values are hidden just below the veneer of a civil interaction.

By contrast with his cold, corporate bullying, hints of something more emotive shine through from the recipient’s side. Sneeze, tingling, and cry are all physical, tactile words, and the image of her head floating off into space is the most lively and stimulating of the whole poem. Her words come across as honest, especially when she admits that she’s overwhelmed: I think I’m going to sneeze – or cry! Adcock gives us a glimpse that, behind all the stifling, corporate babble, living breathing people still inhabit the world. While we’re looking at the reactions of the ‘lucky winner’, I’ve read one or two commentators saying the poem is about greed, or about our desire to get ‘something for nothing’ – but I’m not sure I agree with this interpretation. To begin with, the recipient of the call is flabbergasted by the news and skeptical to hear they’ve won more than a million. Her instinctive, first reaction is to express pure disbelief, ‘I just… can’t believe it,’ and, to be honest, she never really gets beyond that reaction: almost the last thing we hear from her is ‘I’ll believe it when I see the cheque’, Adcock using repetition of the same phrase to drive home this theme. The caller lays it on thick, repeating million, million and millionaire three times in the first stanza alone, hoping to tempt her like the devil seeing if she will sell her soul. But, to her credit, she doesn’t immediately fall into his trap. She replies reluctantly, suspecting that not everything is as cut-and-dried as it appears to be. There’s a long literary tradition of poems exploring the tug-of-war between the heart and the head and the caller’s proposition pits his victim’s logical sense of disbelief against hope: I can feel the push-and-pull of temptation fighting reason throughout Adcock’s poem.

On one hand she’d love to have such a large sum of money drop in her lap out of nowhere. On the other hand – it all seems too good to be true and her logical sense just about holds her emotions in check so she never runs away with herself. In verse four, just as hope seems to have won over disbelief, she pulls herself back from the edge with a sudden ‘Hang on!’ before restating her concerns about this whole unbelievable conversation. In verse five, when pressed, she uses vague language such as incredible and marvellous to describe her emotions, words that contrast with her need to see something more concrete as proof: she says I haven’t bought a lottery ticket and asks to see the cheque, both of which are physical representations of the money she’s been promised. The simile she uses to describe her incredulous feelings (revolving like a flying saucer) associates with disbelief too – flying saucers are always discredited when it turns out they were just weather-balloons or something mundane. If you’re being uncharitable, you might say the news has made her a little grasping and she does eventually ask ‘But what about the money?’ Still, it’s worth debating here who planted the idea in her mind in the first place – would she crave it if she hadn’t been promised it? I think the pattern of her reactions follows the way disbelief slowly turns to hope and I don’t think we should hold it against her that, while she finds it hard to accept her good fortune, later she wants to take advantage of it, against her better judgement perhaps.

To be honest, this poem is all about the ending either way. The last verse is genius, twisting everything you’ve read upside down, and making you realise that the phone conversation you’ve been following is something completely different to what you thought it was. The way the company rep replies to her final question (‘Oh… we don’t deal in money’) is a weighted reminder that, no matter how much we might think about money, the ‘meaning of life’ is much more than counting pennies. While we often get caught up in the rat race, measuring the worth of our existence through financial success, we forget that life is for having a great experience… something you’ll remember. As the famous saying goes: ‘after all, you can’t take it with you.’ A lot depends on his tone when he says: That’s your prize. Is he harshly crushing her hopes – or is there a touch of sincerity in his voice? If the prize is life, then we’re all winners anyway. It’s up to you to respond to his revelation in your own way: Do you think the caller has been cruelly twisting the knife, relishing her discomfort and feeding off her emotional responses? Or do you believe his purpose was not really to prank her, but to deliver an important reminder about life’s priorities before it’s too late?

For me, bubbling away beneath the surface is the nagging impression that the telephone call is actually the last thing anybody hears before passing from this world into the next. There are frequent hints that the caller is more like a supernatural or otherworldly being than a real person: for starters, his or her identity is hidden behind the plural they and whoever he or she really is, they seem much more powerful than they have any right to be: the idea of a Universal Lottery for which you don’t have to buy a ticket suggests the lottery is a direct metaphor for life – and the caller’s in charge! His retrospective chances module implies he’s a force of fate and the whims of his computer have the power to change the course of a person’s life. Little words scattered throughout the poem can be pieced together like a puzzle: he says everybody’s bought a ticket once and when he says that’s what they all say I wonder if he literally means everybody! Lineation (the choice of which words to begin and end a line) plays a part in this interpretation: dead is the last word of the poem. You might argue the line went dead simply refers to the metaphorical death of her hopes for scooping the jackpot – but it may suggest something more permanent is about to happen at the same time! Her physical symptoms – dry throat, tingling, crying – can be transposed into this scenario too, should you have a mind to read the poem metaphysically. When the call’s recipient admits I feel the top of my head has floated off, out through the window… the image resembles the way a soul is commonly depicted leaving the body and ascends to heaven.

It’s up to you, and if you don’t agree with the ‘voice of God’ theory – no problem. The poem works as a hoax call, an expose of corporate creep, and a reminder to set our priorities straight when it comes to money just as well. The poem implies that reassessing our outlook on why we’re all here is something we might like to do sooner rather than later, especially if you believe that one day we’re all going to get a call from Universal Lotteries. In Ancient Greek mythology, Charon’s duty was to ferry deceased souls across the River Styx into the underworld. But he is far from unique. Christianity has St Peter guarding the pearly gates of heaven and deciding who goes through and who doesn’t. Ancient Egyptian culture gives us Osiris, who would meet departed souls in the Hall of Judgement, where they would plead entry to the underworld. Japanese folklore features Izanami, the creator of the islands of Japan and now a Goddess of death. The list goes on. Is Adcock’s poem a snappy, up-to-date re-imagining of a death-myth in disguise? In this case, the disembodied voice is like the voice of God or a threshold guardian inducting us into the afterlife; capricious, yes, as Gods sometimes are, but also reminding us of the true purpose of life. You’ve had a good experience, right? could simply be referring to this one phone call, and the rollercoaster ride of having her hopes raised then dashed so abruptly – or he could mean her entire life experience. I think both options are on the table.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- For Heidi with Blue Hair by Fleur Adcock

A fraught telephone call is central to this poem as well, highlighting the way communication doesn’t always equal connection or understanding. When Heidi dyes her hair blue she’s sent home from school – much to the anger of her father – but her friends stand with her in a moving scene of solidarity.

- O Me! O Life! by Walt Whitman

Life isn’t always easy and we may be distracted by all kinds of things – money in Adcock’s poem, suffering in Whitman’s. At the end of the day, he too comes to the conclusion that the purpose of life is for living, nothing more.

- Children of Wealth by Elizabeth Daryush

The poem describes a child of privilege who lives life protected in her house, sealed up behind thick glass windows and insulated from the winter weather, safe and warm. Daryush urges the child to ‘Go down, go out…’ into the heart of winter and feel the cold of the snow. As Adcock would remind us, Experiences are what we deal in, right?

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Telephone Call at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining the effects of enjambment, caesura and lineation in this poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Adcock’s poem? Do you agree or disagree with the idea that the poem isn’t about greed? Who do you think the disembodied voice on the end of the phone really belongs to? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

The work will help me a lot with my school assignment. As a literature student, it’s good to have different types of articles, with different perspectives on poems and text

Hi Smriti –

I’m very happy you find different perspectives useful. Thank you so much for your nice comment – and best of luck with all your studies.