See the lengths A.R.D. Fairburn will go to bury the misery of romantic failure.

“One of the most extraordinary men born in the Southern Hemisphere.”

Frank Sargeso, New Zealand novelist and poet; A.R.D. Fairburn was born in New Zealand 1904 and died in 1957.

Coming-of-age is a popular literary and filmic genre that depicts a universal human experience: making the transition from childhood to adulthood. Sometimes, coming-of-age can be a slow process, marked by various events which confirm life is changing. Not here. Eager to get on with the business of adult life, our ghoulish speaker grabs his moment by the throat (no pun intended). Published in 1930 as part of the collection He Shall Not Rise, the poem opens with the word tonight, as if to declare that right now – right here – is the site of his transformation. There’s no preamble or scene-setting to build up the tension. The first thing we witness is the brutal killing of the speaker’s childish self:

Tonight I have taken all that I was and strangled him pale that lily white lad. I have choked him with these my hands these claws catching him as he lay a-dreaming in his bed. Then chuckling I dragged out his foolish brains that were full of pretty love-tales heighho the holly. And emptied them holus bolus to the drains those dreams of love oh what ruinous folly. He is dead pale youth and he shall not rise on the third day or any other day sloughed like a snakeskin there he lies and he shall not trouble me again for aye.

Actually, the archetypal coming-of-age story resembles another literary story structure: the hero’s journey or monomyth. Popularized by Joseph Campbell’s seminal work The Hero of a Thousand Faces, a particular stage in the journey is called ‘Death and Rebirth.’ Campbell theorised that a hero always begins life as an ordinary person who, through a series of trials and tribulations, learns the skills and abilities needed to overcome adversity and triumph over his or her enemies. To become a hero, a person must outgrow their childish self, who will symbolically ‘die’. You can find Death and Rebirth (Campbell also termed this transformational process as being inside the Belly of the Whale) in any number of stories, myths and legends: from Pinocchio – where the hero was literally swallowed by a whale – to Harry Potter, who was killed and reborn in the final book of the series, to Luke Skywalker (who tumbles into the ‘belly’ of Cloud City, only to rise as a hero afterwards), to Iron Man, who basically dies in a cave (that whale’s belly again) and is revived with an artificial heart, and so on. Following the tenets of the monomyth, in order to enter the adult world, our speaker’s childhood-self first must die.

What’s slightly unusual about this version of the coming-of-age tale is the macabre delight taken by the speaker in killing his younger self. In many coming-of-age stories, the hero may be reluctant to leave his childish innocence behind. But Fairburn’s speaker positively revels in the ghoulish act of choking the life out of his young alter-ego. As readers, we are thrown headlong into a blood-soaked scene, forced to witness the brutality: Tonight I have taken all that I was and strangled him pale that lily white lad. The immediate action of the poem is wrenching, which neatly suggests the way that life’s changes can sometimes be shocking. The violence doesn’t let up. The third and fourth lines reiterate the action of the first two, and we see the killing again as if the poet is reliving the same murder from a different angle. Make a list of verbs in the first couple of stanzas and you’ll find yourself looking at the outline from a horror-movie murder-scene: strangled, choked, catching, dragged. The inherent violence of these actions is reinforced though both alliteration and consonance (alliteration refers to repeated letters at the beginning of words while consonance is repeating letters within words as well) . A category of alliteration called dental is made using the letters T and D. In the first two lines alone, you’ll find: Tonight, taken, that, white lad as well as a plosive P: pale. A mixture of hard consonant sounds that do not blend is cacophony. Quickly scan all those violent verbs and you’ll find all kinds of consonant sounds – dentals, plosives and gutturals (G, hard C and K) – as if the writer is assaulting your ears as much as assaulting the young version of himself.

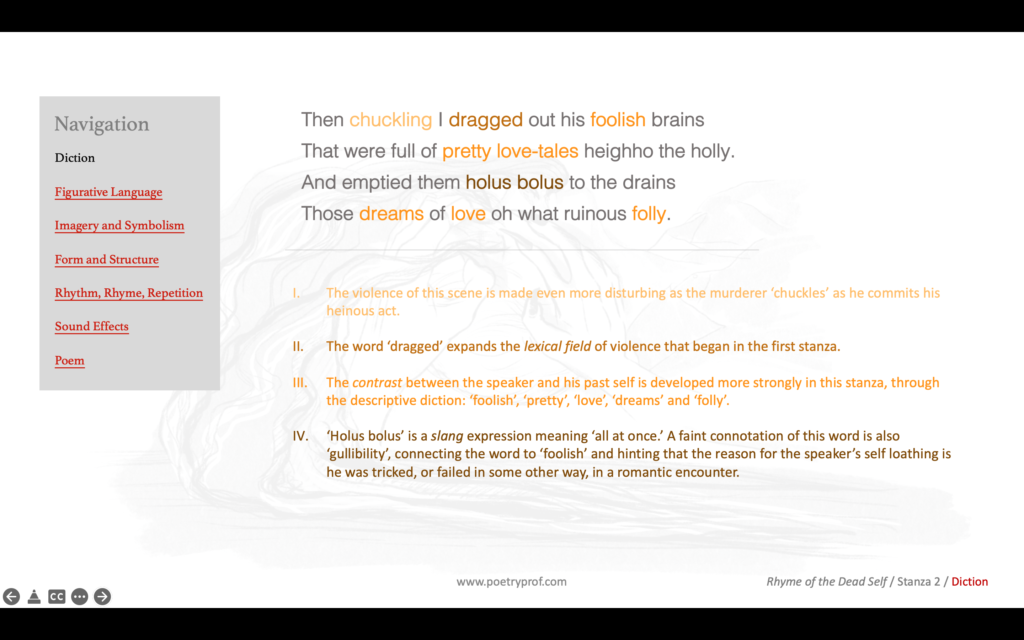

Something unusual about this iteration of death and rebirth is the relish we hear in the speaker’s tone of voice as he undergoes his transformation. He’s chuckling like a maniac as he drags out his own brains and we can visualise him rubbing his hands in glee as he stands over his own broken corpse. There’s a clear sense that the speaker despised his younger self for his naivety and cowardice. Lily white is a colour symbolically associated with cowardice (pirates call those afraid of the sea ‘lily-livered’) and lad is a diminutive, spoken in a sneering tone of voice. He calls him foolish, accuses him of being a dreamer and cruelly mimics the way he would sing childish songs like heighho the holly. In fact, the entire diction of the poem can be sorted into two opposing categories or lexical fields: the harsh, unforgiving diction of the murderer, expressed in words such as strangled and choking, which contrasts with words to do with naive romantic failure (dreams, folly, foolish, pretty love-tales) in the other. Only once does the pace of the action sag, and that’s when the speaker looks – almost wonderingly – at his hands, metaphorically transformed into savage claws. In this part of the poem, Fairburn employs a particular figurative device called synecdoche, by which a part of something stands for the whole. In this case, the speaker’s claws symbolise the triumph of his evil, savage side over the soft dreamer that he used to be. The reader is entitled to wonder, what kind of man is he going to be from this moment onward?

In the second stanza, we discover the mistake his younger self made: dreams of love. Associating these dreams with foolishness and childish naivety, he snarls that his previous dreams of love are just a folly. Meaning a naive mistake, folly is emphasised in the strongest possible terms by the word ruinous, a hyperbole for ‘disaster’. The word folly is joined by rhyme to the peculiar phrase heighho the holly, which the speaker cheerfully hums along as he chokes the life out of his victim. Actually, this phrase comes from Shakespeare’s play As You Like It, in which he wrote:

Heigh-ho, sing heigh-ho, unto the green holly. Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly. Then heigh-ho, the holly.

This allusion helps us infer that this bout of self-loathing was spurred by romantic failure and the symbolic killing of his younger self while he sleeps and dreams represents his determination never to make such a mistake again. Repetition of the words love and dream strengthens the suspicion these offences led to the cruel demise of the speaker’s innocent alter-ego, as does the admission that he slaughtered him while he lay a-dreaming. Despising himself for not learning the lesson ‘love hurts’ first time around, our killer has taken the idea of ‘once bitten, twice shy’ a little too much to heart and is putting his younger self out of his misery once and for all.

As if things weren’t graphic enough, Fairburn’s decision to write his poem like a children’s nursery rhyme is an effective way of accentuating the gruesome images. You may have watched a chilling film in which a terrifying scene is played out to the soundtrack of plinkety-plonkety music. In Rhyme of the Dead Self the murder is recounted to us in a sing-song rhyme scheme (ABAB) and using simple iambic rhythms. Iambs are measures of two syllables arranged in a de-dum pattern. Occasionally, Fairburn brings anapests into the mix: three syllables arranged unstressed-unstressed-stressed. This iambic-anapestic combination is a fairly conventional rhythm employed in ballads and other musical poetry. Wrap all this up in simple stanzas of four lines each (called quatrains) and – hey presto – you’ve discovered the form of the poem, a traditional song. Being forced to visualize such a grisly scene played out to the soundtrack of a children’s verse is the blackest of dark humour. Additionally, the youthful language of the poem throws into stark relief the themes of childhood vs adulthood, innocence vs bitter experience. After all, the image of pulling out a person’s brains and flushing them down the drain is accompanied by a childish idiom, holus bolus, that has the denoted meaning of ‘all at once’ but can also connote childish gullibility as in, ‘he swallowed that lie all at once.’ There’s a comic irony in the killer disposing of his victim’s brains holus bolus – and in him humming the childish songs that he so despises as he does so.

Actually, there’s an interesting rhythmical variation in the second stanza that neatly conveys the idea of transformation from boy to man. We’ve previously seen that the poem is written in measures (feet) of iambs and anapests. Whether two or three beats, both iambs and anapests are arranged weak syllable to strong syllable: the pattern is (unstressed)-unstressed-stressed. Rhythms that move from weak to strong in this way are called rising rhythms. Eagle-eyed readers will already have spotted that two of the lines in stanza two are, though, extended by an extra unstressed syllable, like this:

Then chūck/ ling I drāgged/ out his fōol/ ish brāins/ That were fūll/ (of) pretty lōve/ -tales hēigh/ ho the hōl/ (ly.) And ēmp/ tied them hōl/ us bōl/ (us) to the drāins/ Those drēams/ of lōve/ oh what rū/ inous fōl/ (ly.)

This addition of a single syllable on the end of lines of poetry is called catalexis, and it has the effect of transforming the rising rhythms of the poem into falling rhythms. Interlacing these rising and falling lines mirrors the intersection of childhood and adulthood in the poem and forms a rhythmical tension between the battling halves of the speaker; his innocent and monstrous sides.

Of course, what happened tonight was more of a massacre than a fair fight. The beginning of the third stanza is marked with a shift to the present tense, He is dead, pale youth. Through repetition of pale, the speaker makes it clear that there will be no more foolish naivety, that kind of thing is over with now. He’s choked off the youthful, naive side of him, and only cold scepticism remains. His determination never to repeat the mistakes of youth is demonstrated through modals: he shall not rise… he shall not trouble me again for aye. Little words like ‘shall’, ‘must’, ‘need’ and ‘will’ are modal verbs; their function is to indicate strength of feeling and degree of certainty or possibility. Shall is on the strong side (modals like ‘might’, ‘may,’ and ‘could’ are much less sure) indicating certainty that his foolish naïvety is dead and buried, like a brained and dismembered body, deep out of sight.

The poem ends with a slight tonal shift. Gone is the frenzied action of the first couple of stanzas, and we are left with something a little more contemplative. The newly formed, harder and crueller adult stands as if emerged from a chrysalis, looking down at the husk of his former body: sloughed like a snakeskin there he lies. There’s two ways you can go with your analysis of this image. On one hand you might agree that, arguably, this is the only pleasant line in the poem. The longer and softer vowel sounds of the word sloughed suggest a release of anger and aggression, a feeling that extends through the use of soft sibilance in the rest of the line. The word is rather lovely, meaning ‘to shed skin,’ as a snake does when it’s ready to grow into the next stage of its life. Not only does this image bring home the theme of transformation, you may think that it also suggests that change, however shocking and painful, is a natural and necessary part of growing older. Alternatively, you might like to take the hard line on this image: through biblical associations with the story of Adam and Eve and mankind’s fall from paradise, the snake easily symbolises negative character traits such as duplicity, deviousness and evil. In this case, the sibilance here (sloughed, snakeskin, lies) simply underscores the sinister side of the speaker’s personality. After all, once his skin is shed, a snake is still a snake.

And finally, Fairburn doubles down on his religious allusions (no wonder: Fairburn’s great-grandfather was a missionary who arrived in New Zealand in 1819), giving us the line he shall not rise on the third day or any other day. In scripture, the number three is one of the so-called perfect numbers, and possesses a multitude of connotations to those learned in the Bible. One you may like to know about is that according to Matthew, Jonah was ‘three days and three nights in the belly of the whale‘ – therefore after his crucifixion, Jesus would lie for three days and three nights in the heart of the Earth before his resurrection. Here, the speaker seems to deny all possibility of resurrection – he shall not rise – suggesting that, not only has he choked off his younger self, but also ‘killed’ the nicer and kinder parts of his personality (another connotation of the number three in religious terms is the three virtues of faith, hope and charity), including the side of him that wanted to love and be loved in return. This self-inflicted mauling is, in reality, a desperate attempt to harden himself against the pain and hurt that romantic disappointment can bring.

Whether that’s enough to make you feel a tiny bit sorry for him is up to you to decide.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Down On My Luck by A.R.D. Fairburn

Fairburn often wrote about love, life and human experience – but many of his poems have a comic or humorous edge (in the case of Rhyme of the Dead Self, very blackly comic). In this poem, he writes about a person who, down on his luck, wanders aimlessly, hoping to find his way to the next stage in his life. In this powerfully angry poem, he tackles the issue of poverty and wonders at the corruption that allows so few to enrich themselves at the cost of so many.

- First Love by John Clare

Clare also wrote about the pain and disappointments of unrequited love. In this famous poem, love strikes like a lightning bolt and turns the speaker’s world upside down.

- Rite of Passage by Sharon Olds

In this funny-but-sad poem, Sharon Olds laments that, for boy at least, growing older seems to be associated with violence, and a necessary adjunct to becoming a man seems to be the need to ‘kill’ a childish version of oneself.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Rhyme of the Dead Self at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on exploring the poet’s use of rhyme, including different kinds of rhyme scheme and types of rhyme.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of A.R.D. Fairburn’s poem? What else do you think died along with the speaker’s younger self? What did you think of the contrast between graphic content and singsong style of this poem? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Gj daisy🌞