Follow Henry Wotton’s step-by-step guide to peace and contentment.

“Diplomat and author, who was Britain’s ambassador to Venice for nearly twenty years.”

The National Portrait Gallery

If you’re somebody who likes to read the Agony Aunt section of a monthly magazine or books about finding happiness, then today’s poem is definitely for you. The Character of A Happy Life reads like the 17th century equivalent of a self-help guide, written by eminent diplomat and traveller Henry Wotton. In this ambitious poem, Henry sets out to distill the secrets of happiness and writes about how one can attain this elusive state of being. His advice is varied and plentiful and over six verses he probably lists a couple of dozen dos-and-don’ts for you to unpick; however, despite the sheer number of suggestions he has for us, there are some core themes that he returns to time and again. It’s very important to Henry that a person should be able to control their own thoughts and actions, and not blindly follow in the footsteps of others. He also warns against the false trappings of material success and the temptation of, shall we say, questionable habits (which he terms vice) as a substitute for true happiness. At times, the poem is quite didactic in tone (didactic means that the writer deliberately sets out to teach readers a lesson or impart a moral) which was not unusual for pieces written in this period of English writing. So, without further ado, let’s discover secrets to finding happiness for ourselves- explained later in six easy steps:

How happy is he born and taught That serveth not another’s will; Whose armour is his honest thought, And simple truth his utmost skill! Whose passions not his masters are; Whose soul is still prepared for death, Untied unto the world by care Of public fame or private breath; Who envies none that chance doth raise, Nor vice; who never understood How deepest wounds are given by praise; Nor rules of state, but rules of good; Who hath his life from rumours freed; Whose conscience is his strong retreat; Whose state can neither flatterers feed, Nor ruin make oppressors great; Who God doth late and early pray More of His grace than gifts to lend; And entertains the harmless day With a religious book or friend; This man is freed from servile bands Of hope to rise or fear to fall: Lord of himself, though not of lands, And having nothing, yet hath all.

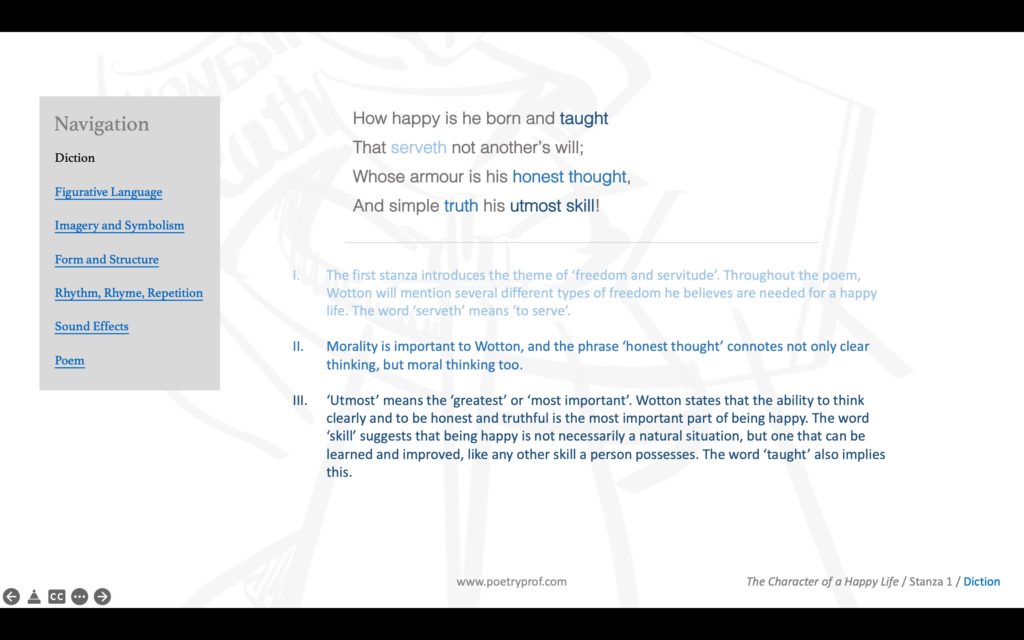

#1: Pay Attention at School, Kids.

Henry’s poem begins with a simple statement of intent: How happy is he… You can think of this as the poet’s central thesis (or theme) that the rest of his poem will go on to elaborate upon. He sets out his stall with strength and determination, using a particular type of alliteration called aspirant. Made with the letter H, aspirant is a good way of expressing emotion (think about the way you might expel a big breath) and conveys both Henry’s assertiveness and sets a ‘happy’ and upbeat tone for the verses that follow. Throughout the poem, Henry will employ a type of repetition called anaphora (which is repetition of words and phrases at the beginning of lines of poetry). Take a moment to count the number of lines beginning with the word whose (or who). The effect of anaphora is to give Henry’s poem that assertive tone, as if he is a wise and experienced teacher delivering a moral lesson to you, dear reader.

Some writers advise you to begin with your strongest argument, and it’s up to you to decide whether that means Henry’s first piece of advice is his most important. Crucial to a person’s happiness is the ability to think for oneself. He uses the word taught to suggest this process is a lifelong lesson that one should begin almost as soon as one is born. He warns: serveth not another’s will, implying that people who have independence of thought and control over their own decision-making tend to be happier people. While this might seem self-evident to you and I, and is one of the core purposes of modern education, remember that Henry was writing in the late 1500s and early 1600s. While not wanting to generalise, it’s true that many ordinary people in Henry’s day would not necessarily have had the luxury of independent thought. Literacy in England at the time of Henry’s death (in 1639) hovered around 30 percent – for men (women’s literacy struggled to break one in ten until the 18th century) – and most people had finished school by the time they were seven or eight years old. In this context, Henry’s idea that one must be born and taught is not something that we should take for granted!

However, let’s not kid ourselves, Henry’s audience was most likely to be gentlemanly (remember he was a diplomat and a man of letters) so anyone with access to poetry like this was surely educated. You may already have noticed the way his hypothetical listener is a ‘he’, which we should try not to hold against him too much. Henry exhorts those lucky enough to possess an educated mind to put critical thinking skills to use as a form of protection against dishonesty and deception. His metaphorical comparison of clear thinking to a suit of armour sets the pattern for Henry’s use of figurative language throughout the poem. In this example, the idea of being armoured in honest thought suggests that a person who thinks for themselves will be protected against ‘weapons’ of dishonesty, flattery and deceit, as one wearing plate mail would be protected from sword blows. Similarly, when he suggests that truth can be wielded as a skill, he is speaking figuratively. What’s interesting about these metaphors is they convey the idea that concepts such as honesty and truth can be learned; in Henry’s view, these are not inherent character traits. Nobody is born wearing armour; armour is forged and acquired, shaped and worn. In this way Henry suggests that happiness and contentment, insofar as it relies on honesty and truth, can be acquired through patience, skill and learning. In modern parlance, we might say that Henry has a growth mindset.

#2: Keep Calm and Stay Balanced

Henry reiterates the idea of independence at the beginning of this stanza, writing whose passions not his masters are. Reiteration is a form of repetition by which the same idea is expressed in a different way, and you might like to compare the first line of stanza two with the line serveth not another’s will. What’s different here is that Henry cautions you against being ruled by your own emotions (passions), by which he surely means powerful negative emotions such as anger or fear. Henry appears to be a logical man who likes to keep an even temper, an idea that he’ll return to in the fifth stanza when he mentions the value of grace. Another thematic seed that is starting to bear fruit is that of ‘freedom and servitude’, revealed through a lexical field of words such as serveth, master, untied, rules, freed (twice), oppressors, servile bonds and Lord. So, throughout the poem, Henry keeps linking the concept of happiness to that of different ‘freedoms’: freedom of thought, freedom from anger, from oppression, and from the illusory temptations of the material world.

The second verse also introduces a stylistic feature of Henry’s poem, which is the use of contrasting words – often binary oppositions – to suggest that happiness lies not in the extremes of life, but by finding a way to walk the middle path. In this stanza, Henry presents public fame and private breath as binary opposites which prevent one from finding one’s own, unique path through the world. In the case of public fame Henry warns us that seeking adulation and adoration from others will lead one to care too much about what people might think of you; in our social-media-dominated world, where grubbing for ‘likes’ on Instabooks and Facetoks creates constant anxiety. this advice seems particularly apt. Henry’s solution, though, is not to retreat into the opposite world of private breaths, a phrase which implies insularity can be as damaging and distracting as the criticism of others. Later, he’ll mention rumour as a force that might undermine happiness, which collocates neatly with the dangers of both public fame and private breaths. A consistent theme of Henry’s advice is that plotting a route through the middle, finding a course that avoids the pitfalls of either extreme, is the path that most likely leads to happiness. After all, anything we achieve in this world is transitory and will eventually fade or crumble into dust, a fact that Henry reminds us of in the second line of verse two. Paradoxically, to be truly happy we must accept our mortal limitations and ensure we are mentally prepared for death.

#3: Beware of a Whole Load of Things.

As the poem develops, you may feel it starts to sound a little list-like, and no verse is more guilty of this than the third. Henry begins by warning you not to feel jealous of others, particularly those who happen to have succeeded in life (chance doth raise) where maybe you haven’t yet. He pointedly cautions you against vice, which can mean any of a whole host of nebulous immoralities, and is a word that he isolates almost by itself at the start of line two. His warnings echo his previous implication, that happiness balances on stable foundations, so one should avoid extremes of behaviour, whether wallowing in jealousy, cursing your own misfortune, or falling into sin. If you’re finding all this advice hard to follow, read carefully to punctuation and you’ll notice Henry pauses here, using a technique called caesura, which is a deliberate break in the middle of a line of poetry. He uses a semi-colon to create this pause, before continuing with his next piece of advice; in fact, he often relies on the semi-colon to help him separate out the various pieces of advice he wants to give, and even ends some verses using a semi-colon instead of a full-stop. Although you may feel this makes the poem read a little bit like a checklist, it also grammatically links different pieces of advice together. Perhaps he’s implying that each piece of advice is like one piece of a puzzle – only when you put everything together will you be able to see the complete picture.

This next piece of the puzzle, who never understood how deepest wounds are given by praise, seems odd, because it sounds as if Henry is saying that praise, or compliments, can actually cause unhappiness. But remember, his central theme is that being able to think for oneself protects against the illusory temptations of the world. The idea of praising someone insincerely, or being tricked by flattery, or not realising when luck plays a huge part in one’s success, are all ways of being deceived. Or maybe Henry was just ahead of his time, and understood that overpraising someone can be detrimental in the long run! Whatever you decide, don’t neglect the way that deepest wounds extends the metaphor he began back in stanza one with the idea that freedom of thought is a protective suit of armour one needs to protect oneself. According to Henry’s worldview, remember, happiness does not come naturally and is not given for free: it must be fought for and defended, which explains so many references to battle.

#4: Do Unto Others As You Would Have Them Do Unto You

We haven’t discussed morality much so far, but Henry has already alluded to the importance of having a strong moral compass. He’s especially keen for you to avoid sin and vice and, at the end of the third stanza, claims that a happy man doesn’t need laws and decrees to guide him through life (rules of state) – he obeys the rules of good because it’s the right thing to do. He develops this theme further in stanza four, which brings the word conscience into play for the first time in the line, whose conscience is his strong retreat. Once again, he extends the metaphor of battle through the phrase strong retreat – in this phrase, retreat is actually a noun referring to a defensible position, such as a castle or fortress. Yep, it’s that protective metaphor again. Basically, Henry says that, if in doubt, armour yourself in your conscience, that inner voice that tells you right from wrong, and you’ll be happy whatever the world throws at you.

We’ve already noted how reiteration is a major component of Henry’s advice-guide, and those pesky flatterers make their reappearance in stanza four: whose state can neither flatterers feed, nor ruin make oppressors great. This time, Henry employs a particular type of alliteration called fricative. Made with the letter F and TH (neither flatterers feed), here fricatives replicate the whispery, sly tones of those who would gull you for their own benefit and seek to tempt you from that middle path. He ends this verse with a warning not to mistake brute force for true strength; the ability to smash things doesn’t make an oppressor great, and those who seek their own happiness should be careful not to trample and tread on the dreams of others as they do so.

#5: Read the Bible

This one’s pretty simple: as a devoutly religious man in a religious society, it’s no surprise that Wotton might exhort his readers to regular prayer. He wants you to pray twice a day (early and late) and reiterates his warning that happiness does not lie in earthly achievements or the allure of materiality that he first brought up in verse two (untied unto the world). He champions humility and modesty by reminding us not to expect handouts – God does not directly intercede in our lives and we should not overly covet his attention. Rather, ask for His grace, not gifts to lend. It’s becoming more and more obvious that Henry defines happiness as an abstract ideal (such as grace) rather than in the concrete realm of materiality and earthly interests (gifts is a concrete word). Interestingly, Henry’s tone of voice strengthens in these lines through alliteration using the letter G: guttural. Sometimes this can be a hard, unpleasant sound, but I rather think here it suggests strength; not the brutal brawn of those ruinous oppressors, but the kind of strength a resilient person might display in the keeping up of regular prayer, or the quiet fortitude one might get from following his or her religious faith.

Quietness and comfort are the ideas that spring to mind at the end of stanza five, particularly when he mentions how a happy man is content to entertain the harmless day by simply reading or chatting. Despite his previous use of battle metaphors, Henry comes across as a peaceful man (after all, armour and retreats are both defensive measures and harmless is, well… harmless, suggesting a pacifist ideal of life) and the tone of his poem, which has sounded somewhat like a cross between a lesson and a warning, softens as he contemplates whiling away a day in by reading. Is there a faint whiff of personification in the way he mentions religious books or friends, as if one is as good as the other if the purpose is peaceful contemplation or conversation? Whether you agree or not, this religious book is a concrete symbol representing abstract concepts such as companionship, religious devotion and lifelong learning that Henry equates to a happy life.

#6: Find Your Inner Peace

Anyone who’s watched Kung-fu Panda will already know the secret to success, but almost 400 years ago Henry Wotton got there first. And anyone who’s read Rudyard Kipling’s If – will recognise that moment in a poem that signals the end is coming. There’s a subtle departure from the anaphora (Whose… whose…) that’s been a feature of the poem so far, to This… which tells us that he’s about to wrap up today’s lesson just in time for the bell. You’ve probably already realised the poem is written in regular iambic tetrameter, an extremely common and popular rhythmical arrangement (Stephen Fry, in his book The Ode Less Travelled, describes iambic tetrameter as the bread and butter of English poetry) by which each foot of two syllables is organised into an unstressed-stressed combination (called an iamb) and repeated four times in each line (tetrameter). Also, Henry writes in stanzaic form, whereby each verse is four lines long; a stanza of four lines is called a quatrain and, again, this is a frequent choice made by writers in Henry’s time and beyond. And he also employs a simple ABAB rhyme scheme in every verse. Taken together, and because they are deployed with such aplomb, these formal writing choices give his poem a reassuring and trustworthy feeling, as if you’re listening to a wise teacher whose experience you can rely on and advice you should follow.

So, just like a good teacher at the end of a lesson, Henry quickly summarises his main arguments and reiterates some of the ideas that he’s previously brought up. Firstly, he repeats his assertion that a happy man is freed from servile bonds – he wants you to think for yourself and not head in the direction that others set out for you. Servile means to have an excessive need to please others, but this word also has connotations of slavery, especially when used in combination with the word bonds. Although the shackles Henry means are mental rather than physical, he clearly believes that the inability to think for oneself is the equivalent of a life lived only for the benefit of others.

Secondly he reiterates the importance of finding balance in your life presenting a series of extreme juxtapositions, all of which he hopes you will avoid: hopes to rise warns against the dangers of excessive ambition whereas the fear to fall might paralyse one completely in life; Lord of himself, though not of lands repeats his warning against the temptations of material or earthly goods as a route to happiness – the 17th century equivalent of advising you against taking a quick-fix shopping trip to make you feel better about yourself. In both these lines Henry uses simple alliteration (fear to fall, lord… lands) to emphasise his points and make them memorable (actually, Henry’s poetry was not published until after his death; it’s probable that The Character of a Happy Life was intended to be heard, not read, and alliteration is a pleasing way of catching a listener’s ear. Maybe this ‘musicality’ in the poem explains why it was later made into a hymn for singing in church too).

His final line – And having nothing, yet have all – is stated in the form of a paradox, where one half of the line seemingly contradicts the other. But, by now, readers should be attuned to the idea of finding the middle ground as a surer road to happiness. Therefore, the last line neatly encapsulates some of the big ideas we’ve been mulling over up till now. Throughout the poem, happiness has been abstract, unattached to material possessions or worldly achievements. According to Henry, it’s more of a state of mind, a way of thinking independently and, above all, clearly; achieved through taking ownership of one’s own life and decisions, and not letting yourself be ruled by your emotions. Happiness is not impossible to achieve, but one may have to work at it a little. There will be temptations and seductions along the way, and the world is full of people who will beckon you down the wrong path, seeking to trick or deceive you. But, with a little faith in yourself (and in God, of course) it’s possible to find that delicate balance and walk the middle path – the one that leads to a happy life.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- In Praise of Angling by Henry Wotton

Something he didn’t mention in The Character of a Happy Life was one of Henry’s favourite pastimes – fishing. In this wonderful poem he extols the highs and lows of what he calls the ‘worldling’s sport’.

- If – by Rudyard Kipling

Arguably the most famous of all didactic poems, Kipling gives his son some good advice on how to be a proper man.

- That All, Everyone, Each in Being by Mai Der Vang

The daughter of Hmong refugees, Mai Der Vang lives in California and won the 2016 Walt Whitman prize for her poetry. Find out what she has to say about fulfilment in this beautiful and mysterious poem.

- The World is a Beautiful Place by Laurence Ferlinghetti

For a little bit of perspective on the topic of happiness, try this poem by American master Laurence Ferlinghetti. Be warned – the title is deeply ironic.

- Happiness by Karlis Verdins

Finally, in this lovely poem from Latvia, you’ll find happiness can be as simple as eating a boiled egg with a tiny spoon…

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Character of a Happy Life at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It normally costs £2 – but you can download it for free if you look now:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full, analytical paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining stanzaic form as used in this poem and many others.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Henry Wotton’s poem? What do you think makes for a ‘happy life’? Can you recommend similar poems you know? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

I live a happy life. I think of you sometimes. My maiden name was Stenner. Festive wishes to you. I hope you are loved, and well.