Percy Bysshe Shelley exhorts us to rise up in this powerful poetical polemic.

‘Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.’

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE (LINES INSCRIBED UPON SHELLEY’S GRAVESTONE)

It’s not everyday that you read something by someone who thought that “government is an evil” and it is only because of the “thoughtlessness and vices of men” that we have to tolerate governance. In this poem, Shelley rails against those who use their power and positions to exploit the working classes – and also saves some of his ire for those ‘thoughtless’ ones who, like sheep ambling casually towards the slaughterhouse, allow such evil to be perpetrated upon them. This poem was written after the Peterloo massacre (sometimes called the Manchester massacre) of 1819, in which a crowd at a political rally were charged by the local militia, resulting in nine deaths and many injuries. Written at the same time as several other political poems, Song to the Men of England was actually deemed too risky to be published during Shelley’s lifetime:

Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay thee low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

Wherefore feed and clothe and save

From the cradle to the grave

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat – nay, drink your blood?

Wherefore, Bees of England, forge

Many a weapon, chain, and scourge,

That these stingless drones may spoil

The forced produce of your toil?

Have ye leisure, comfort, calm,

Shelter, food, love’s gentle balm?

Or what is it ye buy so dear

With your pain and with your fear?

The seed ye sow, another reaps;

The wealth ye find, another keeps;

The robes ye weave, another wears;

The arms ye forge, another bears.

Sow seed – but let no tyrant reap:

Find wealth – let no imposter heap:

Weave robes – let not the idle wear:

Forge arms – in your defence to bear.

Shrink to your cellars, holes, and cells –

In halls ye deck another dwells.

Why shake the chains ye wrought? Ye see

The steel ye tempered glance on ye.

With plough and spade and hoe and loom

Trace your grave and build your tomb

And weave your winding-sheet – till fair

England be your Sepulchre.

My favourite Percy Bysshe Shelley story is that he once gave up sugar in tea. “So what?” I hear you say. It doesn’t seem like the most exciting piece of information. And, given the out-of-the-ordinary life he otherwise led, I concede it is a little mundane. Consider, though, that he not only gave up himself (his wife second wife, Mary, of Frankenstein fame, also gave up in support) but he spearheaded a campaign which resulted in up to 400,000 Britons doing the same. Why? Sugar consumed in Britain was grown in Caribbean plantations by African slaves, so had become synonymous with the evils of the slave trade. Shelley – despite famously craving sweets, cakes and sugar – switched to green tea so that he could drink his favourite beverage without needing to add sugar.

In 1811, in defiance of his father and grandfather’s wishes, he eloped with and married Harriet Westbrook, the daughter of a London tavern keeper. They ran away to Ireland where he continued to distribute material advocating political rights for Roman Catholics, demanding political autonomy for the Irish, and preaching free-thinking. In 1813, he abandoned his first wife – just after she gave birth to their first child! – and later married Mary Wollestonecraft, against the objections of her father (perhaps because by this time his own family had cut him off and he had been forced to turn to moneylenders; or perhaps because he had already published poetry and essays attacking the evils of the time: commerce, the church, war, eating meat, the monarchy and even the institution of marriage!) His death was appropriately rock’n’roll, not least in that he died much too young at the age of 29. He and Mary had moved to Italy (the hills and lakes, not to mention the incredible storms, would form major parts of the setting of the novel that made her famous) where he drowned when his boat overturned while out on a lake near Livorno.

Shelley’s belief in social justice suffuses this poem which, the title informs us, is directed to the men of England: we can understand this to mean the working men of England: the uneducated, unwashed masses whose labour provided the muscle for widespread agriculture and the industrial revolution, generating unprecedented wealth and plenty through working in fields and factories, often in deplorable, dangerous conditions, the length and breadth of the country. Shelley’s poem isolates three industries which can be seen to represent the bulk of this workforce: farming; textiles; manufacturing. Unfortunately, very little of the wealth and materiél they produced through forced toil was allowed to trickle back into their pockets, most of it concentrating instead in the hands of a privileged few: members of the aristocracy, landowners, landlords and the like. At one point in the poem he quite directly states that these people drink your blood, portraying them as vampires that can only exist by consuming the blood of others.

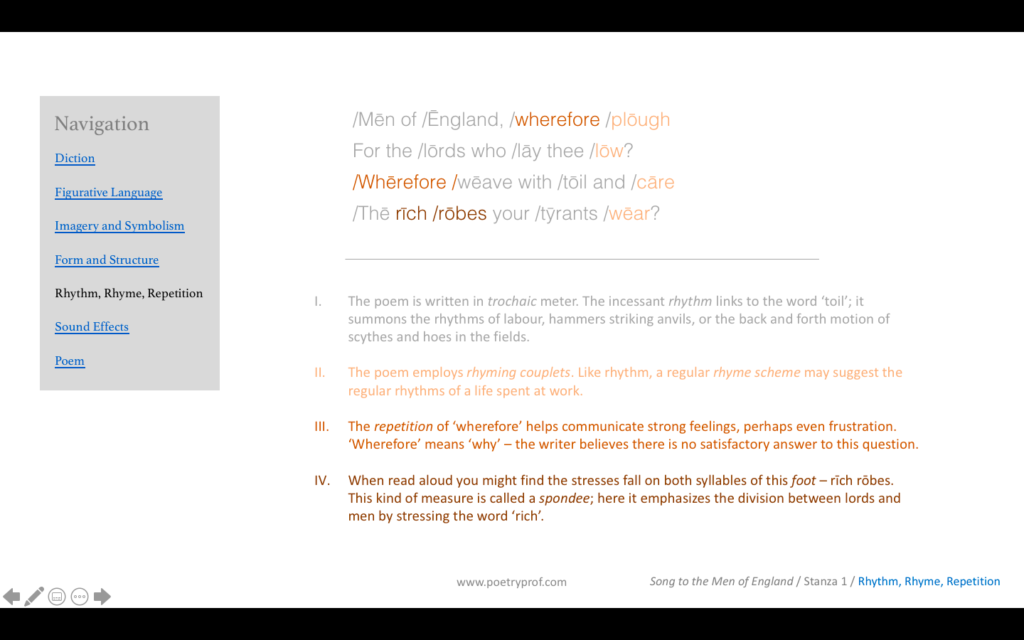

The tone of the opening stanza is one of anger and incredulousness: the word wherefore actually means ‘why.’ Put on your best teenage voice and try mewling ‘Why? Why?’ out loud. Do you hear that indignant tone? Shelley makes liberal use of rhetorical questions here (and throughout the poem): he provides no reply because he considers the answer to be self-evident – there is no good reason why so many strong men should allow themselves to be brought so low by so few. Shelley’s anger is carried through the sound patterns of the opening stanza: alliteration in lords who lay thee low and rich robes; assonance in wherefore, plough, for, lords, low, toil, robes. O can be a deep, round sound good for carrying strong emotion. You might also hear an emphasis on the last word of each line: while the prevailing rhythm is trochaic (two syllables arranged in a stressed-unstressed pattern are called trochees), Shelley has each line end on a stressed beat. Plough, low, care and wear are all verbs, emphasising the notion of work – and work that only benefits others at that.

Shelley’s incredulousness at the passivity of the working classes reaches its peak in stanza 3. Part of the power of his poem comes from repetition– this is the fourth time he asks ‘wherefore’ – why? Listen to how that trochaic rhythm puts an incredulous note into the word wherefore: rhythm serves to underline his anger, and puts emphasis on the rhetorical question – why? You can see that the trochee runs through the first four verses, creating similar effects in each one. For example, drain your sweat – nay, drink your blood is hard to say without overly stressing both verbs.

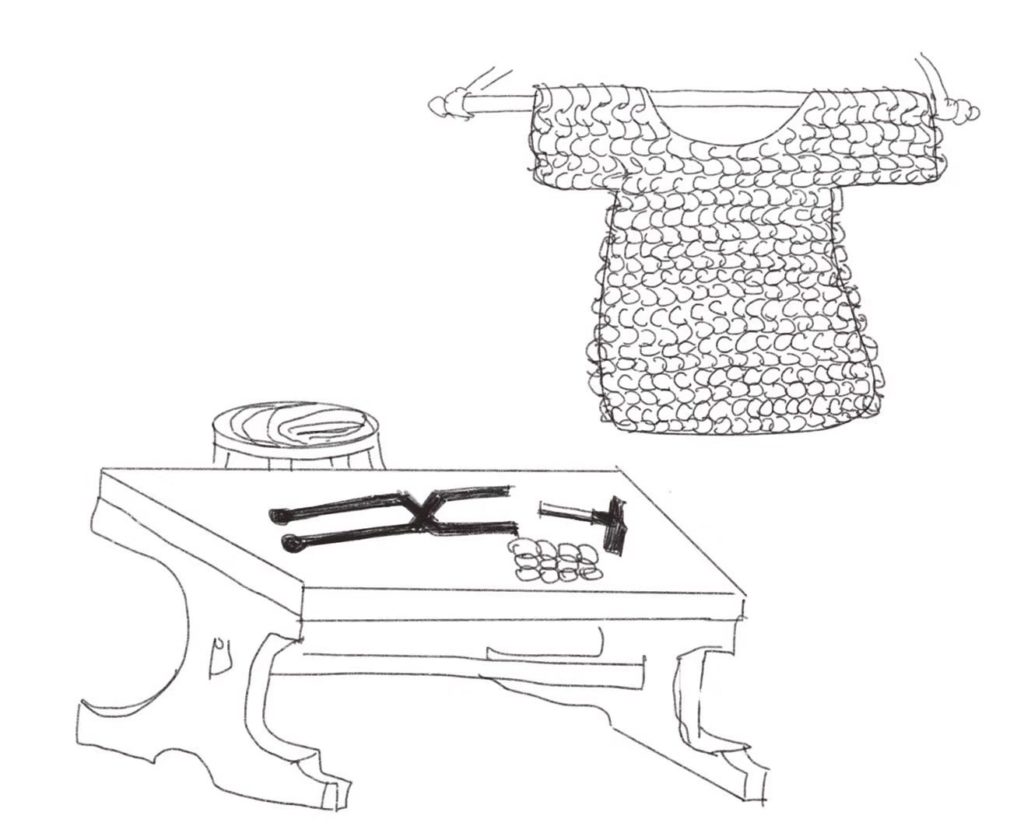

Throughout the poem he casts his critical eye around various institutions and industries, all of whom prop up the wealthy classes and form the backbone of the English economy. Here he directs his gaze onto those who work in manufacturing workshops: forges, blacksmiths and armament factories. He asks why people are willing to fashion the very tools that will be used against them to keep them in poverty:

Wherefore, Bees of England, forge

Many a weapon, chain and scourge

That these stingless drones may spoil

The forced produce of your toil.

The aristocratic classes are interestingly characterised by Shelley as stingless drones, a metaphor that needs consideration as a more obvious comparison might be the queen bee, who lives a cosseted, sedentary life while her workers (Bees of England) see to her every need. However, the queen can be considered to be the heart of the hive, without her the other bees would be directionless and bereft. Shelley doesn’t want to credit the upper classes with such a comparison. He would rather us think about how the upper class are ‘stingless’ – read this as ‘powerless.’ They only have power over the working classes because the working class are complicit in their own exploitation. In my opinion, this is what makes Shelley’s Song to the Men of England much more interesting: he doesn’t spare the workers from their share of his righteous anger. He is angry with the tyrants, yes – but, more so, he is angry with the men of England who wilfully allow such blatant injustice to be perpetrated upon them without resistance. His poem can be read as a protest song – an exhortation to action and call to arms.

One danger of this kind of polemic is that it can become a little one-note. By now, Shelley has repeated the patterns of his poem three times and the use of rhetorical questions as a device to convey disbelief and anger is wearing thin. Shelley begins to switch things up in stanza four, in which he presents the most basic aspects of life (e.g. shelter, food, love) and juxtaposes them against pain and fear. Like any good persuasive speaker, Shelley is fond of patterns of three (also called triple structures and tricolons). We’ve already had feed and clothe and save and weapon, chain and scourge. Check out the first two lines of stanza four – we get two in a row: leisure, comfort, calm, shelter, food, love. His message is clear – the working classes don’t get a single one of all the things they are entitled to, many of which sit on the lowest tier of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

The next two stanzas can be seen as playmates; by themselves they do just fine, but they work much more powerfully together. First, Shelley lays out the state of the things as they are – then, he lays out what he thinks the state of things should be. Look at them placed side by side:

The seed ye sow, another reaps; Sow seed – but let no tyrant reap:

The wealth ye find, another keeps; Find wealth – let no imposter heap:

The robes ye weave, another wears; Weave robes – let not the idle wear:

The arms ye forge, another bears. Forge arms – in your defence to bear.

There’s a clever term for a structure like this: antithetical parallelism. This means the structures of the lines are similar (‘parallel’) but the ideas are opposite (‘antithetical’). So line one of both stanzas is about sowing seeds, line two about finding wealth and so on. The dual stanzas also function as ‘mirrors’ of one another or partners in a question/answer game. In the second stanza, Shelley powerfully uses the imperative tense (also called the command tense, in which the verb is placed first) to order the working men onto a better course of action, and negation (words like no and not) to correct what he sees to be huge social iniquities. His triple structures are subtly at work again: he figuratively labels the exploiters as tyrants, imposters and idle in successive lines.

Following the poetic tradition of the volta or turn (at a certain point in the poem, the writer changes the perspective, shifts the tone, or introduces a counter-argument) the final two stanzas abandon his critique of those in power who exploit the men of England and focus solely on the working classes. Shelley leaves us in no doubt as to his opinion of those who, after reading his exhortations, still won’t stand up for themselves. The final stanzas present the future, for those who want to blindly go on co-operating with the systems that oppress them. You can almost hear the disgust he feels as he tells them, to shrink to your cellars, holes and cells. He employs one more question: why shake the chains ye wrought? But this time he provides an answer: ye see the steel ye tempered glance on ye. In other words, the weapons (steel) you make (tempered) will be used against you (glance on ye) should you try to stand up for yourselves. Rhythm really comes into it’s own in these two lines, imprisoning the words in an iambic de–dum, de-dum beat just as the men are imprisoned by invisible chains. It’s a curious admission to make; he seems to warn that death awaits those who try to revolt against the status-quo.

But what if they don’t rise up? Well the final stanza presents us a powerful image of the whole of England as one giant Sepulchre, a resting place for the dead. Shelley suggests that to live in ignorance – or worse still, complicity – is a form of living death. All people do is build their own graves, tombs and weave winding-sheets (the white shrouds that bodies were wrapped in before burial). The images are so powerful there can be no doubt as to Shelley’s belief – what is the point of a life that amounts to nothing more than slavery? If people are going to die anyway, they may as well do so by claiming what is rightfully theirs.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- To A Millionaire by A.R.D. Fairburn

A poem by a New Zealand minister written in the form of an address to a millionaire, warning about the dire consequences of inequality and corruption. It’s even angrier than Shelley’s Song.

- Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley

One of Shelley’s most famous poems, this piece contains the immortal line: ‘Look on my Works ye Mighty, and despair!‘

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Song to the Men of England at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on exploring the meter and rhythm of the poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for revision or a recap lesson.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Shelley’s protest song? Do you agree that he reserves the strongest criticism for the men of England themselves? What do you think of his descriptions of the upper classes? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.