Whatever you do, don’t pity Edna St Vincent Millay for her broken heart.

If you’ve ever gone through a heart-wrenching break-up, you’ll be able to relate to today’s poem by Edna St Vincent Millay. Sonnet 29, from a sequence of sonnets Millay wrote and published between 1920 and 1923, perfectly captures the way you might try to bury the hurt deep down – but sometimes the armour cracks or the façade slips and grief comes tumbling out. At the same time, Millay explores the age-old conflict between the heart and the head, kicking herself that all along that she knew how this particular relationship was going to turn out – but threw herself in head-first regardless:

Pity me not because the light of day

At close of day no longer walks the sky;

Pity me not for beauties passed away

From field to thicket as the year goes by;

Pity me not the waning of the moon,

Nor that the ebbing tide goes out to sea,

Nor that a man’s desire is hushed so soon,

And you no longer look with love on me.

This have I known always: Love is no more

Than the wide blossom which the wind assails,

Than the great tide that treads the shifting shore,

Strewing fresh wreckage gathered in the gales:

Pity me that the heart is slow to learn

What the swift mind beholds at every turn.

It’s often unwise to assume that the speaker of a poem and the writer are the same person. In this case, however, it’s true that Edna Millay herself had a turbulent love life. Bad luck in love seemed to run in her family. Her mother divorced when Millay was 8 years old and thereafter raised Edna and her two sisters alone. Eventually Edna would marry Eugen Jan Boissevain; but not until 1923 – after Sonnet 29 was written. Until then her life was marked by a string of love affairs; many passionate and intense, most of which ended suddenly leaving Millay distraught more than once. She began to adopt a fatalistic streak towards her loves and lovers, never fully believing that her relationships could ever last. In the third line of Sonnet 29 she pointedly mentions that, once beauties passed away, love always seems to start looking elsewhere as well. These lines from her 1922 Four Sonnets sequence are quite revealing:

But you are mobile as the veering air,

And all your charms more changeful than the tide

…

I would indeed that love were longer lived,

And vows were not so brittle as they are.

In Millay’s experience, love never lasts and her lovers are faithless and inconstant. At the start of her Four Sonnets, she personifies love killing her like a gladiator in an arena:

Love, though for this you riddle me with darts

And drag me at your chariot till I die

Sonnets have long been associated with love poetry; Millay adopts this most traditional of forms yet gives us a totally modern take on the theme of love, derived from her own lived experience: all the let-downs, broken dreams, mistakes, arguments and disappointments of love. Far from being noble gentlemen, her lovers all have roving eyes and unfaithful intentions. What could be a cliché becomes revolutionary poetry that defies expectation. In 1922, published women’s voices were still comparatively rare. Sonnets are filled with women, of course, as long ago as the 1350s when the mysterious Laura was the object of Petrarch’s affections (Petrarch was an Italian master of the love sonnet, so much so that a particular form of sonnet, the Petrarchan Sonnet, was named after him). But in all these poems women were seen, not heard. The voice was always a man’s voice, the feelings described were a man’s experience of love. Women were pictured, praised, longed after and lusted for – but not heard.

Given Millay’s penchant for the unexpected, it’s no surprise that Sonnet 29 begins at the end, rather than the beginning, of a love affair. And it’s also no surprise that the first words we hear are angry, even a bit confrontational: Pity me not. Using the imperative tense, by which the verb is placed at the start of the poem, Millay’s voice is commanding (another name for the imperative is the command tense) and assertive. There’s no simpering here, no secret plea for the ‘now-now’ or ‘dear-dear’ of soothing words. The speaker sounds too proud to accept any platitudes. She buries her hurt deep down and presents a tough façade to the world. Part of that toughness comes through the poem’s use of simple repetition. Pity me not is repeated three times, and, when it stops, nor that… nor that…takes over. Repeating words at the beginning of a line of poetry has a special name: anaphora, and it leaves us in no doubt that Millay has no use for any sympathy we might offer. She also begins as she means to go on, with a subtle inversion of a sonnet’s iambic rhythm (an iamb is a pattern of two syllables arranged ‘unstressed-stressed’). The stresses of the word ‘pity’ are actually arranged ‘stressed-unstressed’, putting extra weight into her firm instruction not to feel sorry for her. Disruptions to iambic rhythms are not that uncommon, so much so they have a technical name: trochaic inversions – although it is unusual to see one employed so early on.

The literary context for the exploration of ‘pity’ can also be traced back to our friend Petrarch, who’s sonnet sequences featured him pining after the mysterious – and unattainable – Laura. Petrarch seemed to actually enjoy the pain of unrequited love and made a great deal out of wallowing in sadness and melodramatic self-pity. His tone must have tapped into some latent zeitgeist as he became something of a popular sensation in Europe. And so, a new literary archetype was born: the Petrarchan Lover, one who revels in the bittersweet pain of failed romance and doomed love. Probably the most famous of all Petrarchan Lovers was Romeo who famously said of the unattainable Rosaline: she’ll not be hit with Cupid’s arrow. By contrast, Millay’s sonnet firmly rejects the stereotype of the Petrarchan Lover, mooching around in despair and wanting people to feel sorry for her. The most memorable aspect of Sonnet 29 is her repeated demands to Pity me not. She’ll later give us the reason: This I have always known. Millay is furious with herself for allowing the emotions of the heart to override her good sense. She wants to hold onto her pain, teaching herself a lesson she feels she deserves, rather than ask others for false comfort.

Another contrast Millay gives us is the struggle of the individual against huge forces of fate and time. Subject to the grinding forces of the tide and the moon, what hope does an individual heart have for holding onto its desires? The first eight lines of the sonnet (technically called the octave) give us a succession of images from the natural world, suggesting the inevitable and implacable passing of time as the world goes about its uncaring business. The first of these is:

Pity me not because the light of day

At close of day no longer walks the sky;

Time passes implacably; this simple idea is made clear through the sonnet’s natural rhythm, the de-dum, de-dum of unstressed-stressed iambic pentameter seeming to mark the time away. Look closely, though, and you’ll see there’s a little more to this image than first meets the eye: the light is personified, giving us a little hint that, if we were to peer to the bottom of Millay’s despair, we’d find an unfaithful man waving back up at us. Light walks the sky like a lover walking away at a whim. Millay identifies the passing away of beauties as the time when her man decided to leave. No wonder she repeats Pity me not with such vehemence – she knows she should have seen it coming.

The next few lines strengthen the suggestion that the stealing of beauty by time is a natural process that can’t be avoided. Without a farmer to tend it, a field will naturally revert to a wild thicket; the ebbing tide that goes out to sea washes away youth and passion too; the moon is described as waning, meaning thinning to an invisible sliver. The kicker comes in lines seven and eight when Millay juxtaposes man’s desire with all these natural processes:

Nor that a man’s desire is hushed so soon,

And you no longer look with love on me.

How you respond to these lines might depend on your own experiences, or even whether you’re male or female. Through equating a man’s fading desire with natural ‘fading-aways’ she’s implying that man’s inconstancy and his easy tendency to lose interest is natural too. I’m not sure what to think about this personally, but have to admit that, from Millay’s point of view, it’s probably true. For a brief moment, her fierce, tough mask slips and we get a glimpse of the raw pain underneath. The rhythm, of course, hits the words you, me, look, love, and long like a hammer driving in a nail. There’s something about the simplicity of the language here (almost all of the accented words are monosyllabic) that strikes a chord, and the way Millay employs negation (nor, no longer) to cast light on what she’s lost is very moving. But possibly the most touching moment of the entire poem is the first time Millay says ‘you’ to balance out all that ‘me.’ That simple little word hits with a jolt: whether he’s still around or already gone, the sonnet becomes a last, desperate attempt to break through to somebody who’s forgotten how to listen.

Sound effects squeeze even more emotion out of this line. Onomatopoeia (hushed) recreates the silencing of passion and mimics the receding tide in one simple word. Coming from a category of alliteration called liquid, the letter L (look, love, longer) combines with sibilance (desire is hushed so soon) creating a ‘liquidy’ sense of movement and flow and the sound of the implacable sea. Assonance is equally potent here. See how O is combined with L, S and N: nor, soon, no, longer, look, love, on, creating a sad, longing sound over and over again. The line ends with me which creates somewhat of a sonic contrast, particularly in terms of the shift from O to E. It’s like a lump in the throat, or the words catching and breaking. It doesn’t matter how much you try to be tough in the face of heartbreak, sometimes human emotion is just too overwhelming and the walls we throw up to hide our pain crack, if only for a moment.

In a traditional Shakespearean sonnet (the kind Millay adopts for Sonnet 29) the ideas in the poem are gathered in two sections: the octave, a break, then the sestet (meaning group of six lines). The little break, marked here by the poem’s first full stop, is called a turn or volta. After this pause something changes. This could be a change of perspective, a new angle of approach, a switch of subject, or something more subtle like a change of tone or attitude. Once you’ve read a few sonnets you’ll get used to looking for the turn and have fun trying to put your finger on what the precise change might be. In Sonnet 29, in the octave, Millay was concerned with the passing of time; now she turns her attention to conveying how love feels in some kind of tangible way.

So, for the next four lines, we are treated to a masterclass in the use of figurative imagery: the transformation of something abstract – love is an abstract, as is hate, justice, friendship, almost any concept or emotion, in fact – into something concrete that can be perceived, heard or visualized. As in the first section, Millay throws images at us with some pace, so you have to read carefully to keep up. One moment, she feels like her love is a wide blossom, an image that suggests delicacy and fragility, the wind easily rips it (assails means ‘attacks’) from the branch and casts it out to sea. In the next moment love becomes a great tide – huge, unstoppable and destructive. Millay applies all of her craft once again in these few lines; sibilance echoes the waves’ mighty crash; guttural alliteration (gathered, gales) hints at the sharp pain of shattered emotions. The word wreckage summons images of boats smashed along a rugged coastline somewhere; it stands out from the lexical field of nature used elsewhere in the sonnet, as if a single human’s desire cannot withstand the forces of fate and nature arranged against it. Contrasts and juxtapositions between large and small, here and there, fragile and strong, suggest the turmoil of Millay’s thoughts, which fly from one to another like that tiny blossom hurled this way and that by the merciless gales.

The structure of a Shakespearean sonnet can be traced most easily through the rhyme scheme: ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG which creates three groups of four (quatrains) and a rhyming couplet that stands a little apart from the rest of the poem. The end of Sonnet 29 is a time for self-chastisement: Millay laments the way that her emotions, symbolised by the heart, always gets the better of her swift mind:

Pity me that the heart is slow to learn

What the swift mind beholds at every turn.

The use of the little article the (the heart and the mind) instead of ‘my’ is quite revealing here, implying that the tendency to act emotionally is universal: everybody shares the same weakness when it comes to allowing their emotions to get the better of clear thinking. There’s a long literary tradition of depicting love as a kind of battlefield between the forces of rationality and the armies of impassioned emotion. In Greek Mythology, this tussle was played out between the sons of Zeus: Apollo and Dionysus. Apollo is like the sensible brother who does all his homework, is never late, dresses smartly and everyone says has great prospects. He’s associated with order, logic, reason and clarity of thought. Dionysus is his irrepressible brother who loves to go out and party; drink, dance and revelry is more his thing, as well as mischief-making and, of course, acting on instinct and emotion. Their literary context is long and varied (Oscar Wilde, Jane Austen, Shakespeare, Thomas Hardy, and many more – all the way up to Steven King – wrote characters who struggled with this opposition). You’ll meet Dionysus in stories where characters act with their hearts rather than their heads, and find Apollo when someone sacrifices their dearest wish for duty or the greater good. Earlier in the poem, the mention of the waning moon hinted at the fading of Dionysian passion. The moon symbolises fertility, is the backdrop to many an amorous tryst and illuminates Dionysus’ playground. Apollo, by contrast, is the god of the sun. The waning moon represents the fading of the emotional impulse – to be replaced by the cold, hard logic of the mind casually saying, ‘I told you so.’

The finality of the rhyming couplet closes the poem like a snap. In the end, it’s not her inconstant lover that Millay is so angry with. It’s herself.

Suggested poems for comparison

- Time does not bring relief; you have all lied by Edna St Vincent Millay

As you can probably see from the first line of this untitled sonnet, Millay conflates the themes of time and loss again, to memorable effect.

- Love, I’m Done with You by Ross Gay

Featuring vomit, bloodstains and bad breath, this poem gives us the dark side of love. Written a century later than Sonnet 29, the two poems nevertheless share the same outlook when it comes to the crummy side of love.

- No, I wasn’t meant to love and be loved by Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib

This 19th century poem, translated from Urdu, personifies love as a ‘lazy marksman’ – he wounds you, then leaves you painfully bleeding to death.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Sonnet 29 at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

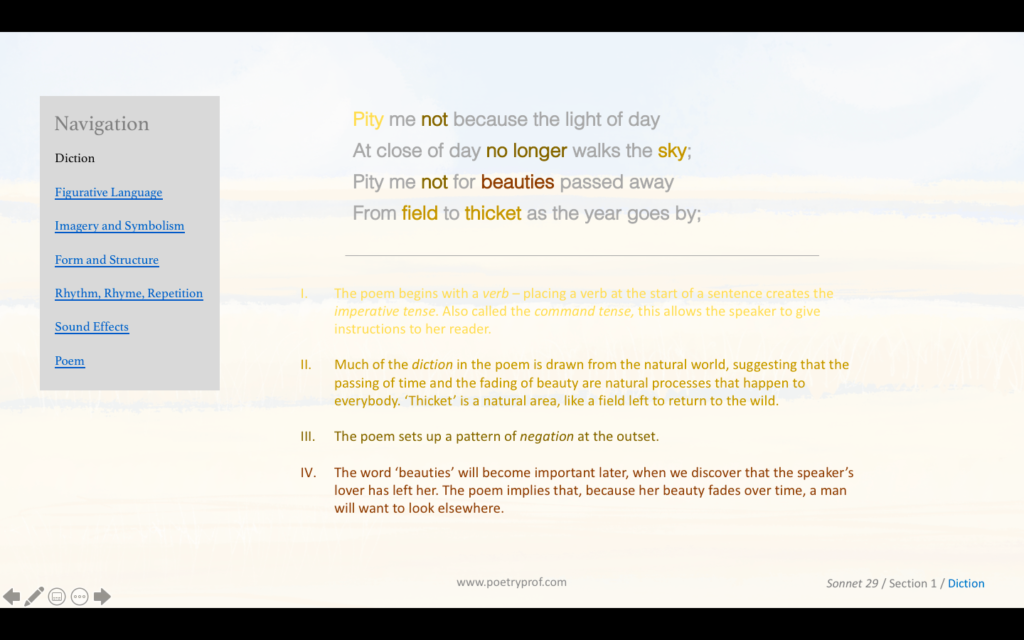

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on exploring figurative imagery.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for revision or a recap lesson.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Edna Millay’s Sonnet 29? Can you relate to her experiences of disappointment and anger? What do you think of the images she uses to depict love? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.