Liz Lochhead casts a spell in this magical realist poem.

“[her writing is] a warm broth of quirky rhythms, streetwise speech patterns, showbiz pizzazz, tender lyricisms and Scots.”

Carol Anne Duffy

In 2011 Lochhead was chosen as the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry winner. During her decades-long career she has also been writer-in-residence for Dundee College of Art, poet laureate for Glasgow, and Makar (the national poet of Scotland). She is one of Scotland’s foremost writers: poet, playwright and performer.

she sat down

at the scoured table

in the swept kitchen

beside the dresser with its cracked delft.

And every last crumb of daylight was salted away.

No one could say the stories were useless

for as the tongue clacked

five or forty fingers stitched

corn was grated from the husk

patchwork was pieced

or the darning was done.

Never the one to slander her shiftless.

Daily sloven or spotless no matter whether

Dishwater or tasty was her soup.

To tell the stories was her work.

It was like spinning,

gathering air to the single strongest

thread. Night in

she’d have us waiting, held

breath, for the ending we knew by heart.

And at first light

as the women stirred themselves to build the fire

as the peasant’s feet felt for clogs

as thin grey light washed over flat fields

the stories dissolved in the whorl of the ear

but they

hung themselves upside down

in the sleeping heads of the children

till they flew again

in the storytellers night.

Storyteller is the introductory poem in a 1978 collection entitled The Grimm Sisters. These poems follow paths trodden by well-known fairy-tales, but the viewpoint is female and the tone is often ironic. The title of the collection alludes to ‘The Brothers Grimm,’ but the gender and syntax is switched. Lochhead’s intention is to restore to a central position those people whose stories are often marginalised or silenced in mainstream narratives: women, lowly workers, domestic servants. The collection also explores ‘storytelling’: the social importance of stories and tales; the power of a well-told story to cast a spell over listeners; how sharing in the telling of and listening to stories can draw a community of people together. As such, this poem presents a lowly female domestic worker in a central position – her work and words fill the scene and illuminate the household. We can see and hear how important storytelling was to people during long, dark winter nights before the coming of electricity and mass communication.

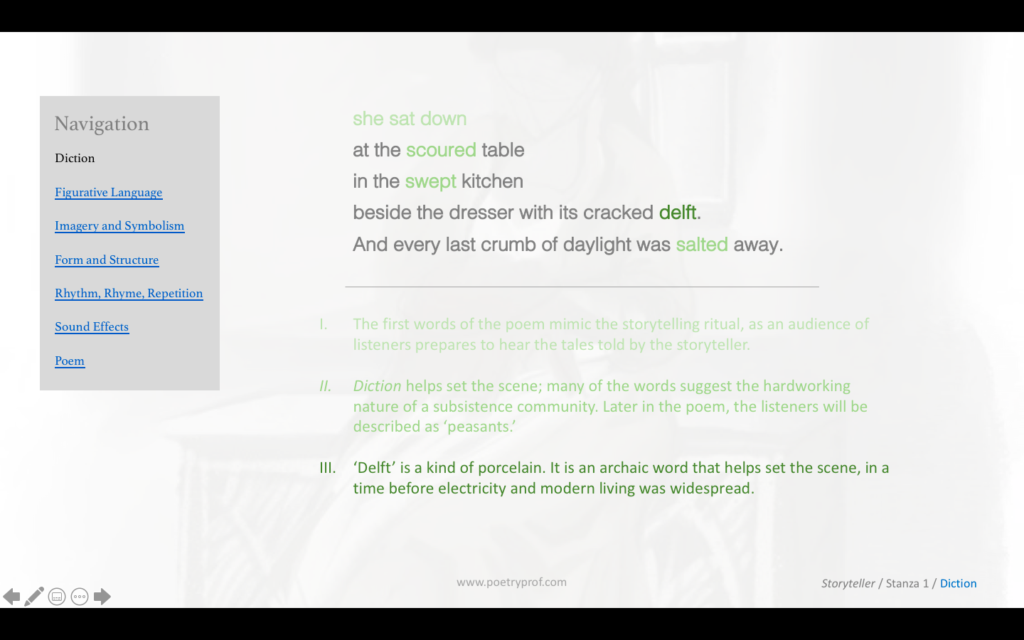

Storyteller’s first line sets the scene: she sat down. The words are simple and unadorned. Even the capital letter is absent, as if this is a scene that repeats every night without rest. One of the most famous storytellers is Scheherazade from One Thousand and One Nights. Each night she would leave her story on a cliff-hanger and take it up seamlessly the next night, keeping her audience – including the king – on tenterhooks. Night by night, Scheherazade postponed her own beheading (eventually the king was so won over by the power of her words that he pardoned and married her!) Lochhead’s storyteller wears the mantle of this literary trope: the storyteller sitting down in front of an eager audience to tell a tale. Think of a primary school teacher in front of her class; a troubadour in front of a crowd; an actor stepping out on stage. Lochhead herself is a prolific performer: the simple physical act of ‘sitting’ signifies the storytelling time has come.

For the next hour or so the real-world melts away, to be replaced by the imaginary world of the storyteller’s design. The story is completely captivating. In the lines below look how enjambment between held / breath creates a little physical pause, as if you are holding your breath, waiting:

Night in

she’d have us waiting, held

breath, for the ending we knew by heart.

You might recognise this feeling of anticipation from sitting on the carpet as your teacher read to the class, or being tucked up in bed listening to one of your favourite stories. It doesn’t matter how many times you heard someone tell it to you, you still enjoyed it over and over again. In this poem it’s not the story but the way the storyteller tells it that her listeners love.

The scene is close and intimate. Her audience crowd into the tiny kitchen, each busying themselves with small tasks (grating, sewing) while they listen. She sits at a kitchen table beside a ‘dresser’ (kitchen shelves displaying pots and pans). The diction Lochhead employs is archaic, drawn from the world of fairy stories: ‘delft’ is a Scottish dialect word for clay pottery; ‘swept kitchen’ alludes faintly to the story of Cinderella; ‘dresser’ is an old-fashioned word. Lochhead writes in the literary tradition of magical realism. Rather than point to a specific time and place, she wants to capture a feel: timeless, historical, before electric lights and television screens, a time when nights still hid imaginary terrors and the spoken word contained spellbinding power. Other diction points to the realities of subsistence living: scoured, swept, cracked and salted all suggest physical labour, hardship and privation. Lochhead makes it easy for us to imagine the peasants and servants crowding into a tiny kitchen after a hard day’s work, ready for their evening meal and nightly story by the warmth of the stove.

The first line of the second stanza is the key idea in the poem: no one could say the stories were useless. Telling stories is another kind of work, as vital to the community as salting fish, scouring clean the table, planting in the fields or stitching clothes. It is different because it is not physical work: but telling a vivid story is its own art and skill and is just as important. Lochhead writes as the tongue clacked at the head of a list of other tasks on which her audience absent-mindedly work as they listen: grating corn and repairing (pieced, stitched, darning) worn clothes. The strongest sound in the poem so far is the onomatopoeia word clacked. Drawn from the vocabulary of weaving at a loom, this sound word effectively allows the storyteller’s voice to dominate the scene and equates her art with the work of weaving cloth.

In both the first and second stanza, whether to bring alive the sounds of housework or to suggest the artful mastery of storytelling, the words of the poem leap from the page and into your ear. Try reading it aloud: in stanza one the simple action of the broom comes to life through sibilance: she sat, scoured, swept, beside, dresser, last, salted. In the second stanza fricative F sounds suggest fingers brushing cloth: five or forty fingers. Plosive and dental alliteration bring to mind the physical action of needle punching through fabric: patchwork was pieced… darning was done. But that’s not all – through careful sound matching (an effect called euphony) Lochhead’s scene is peaceful, warming and quiet. Sounds of housework are in the background, they run underneath the storyteller’s words like a musical accompaniment.

In the first of two figurative comparisons, the storyteller’s art is directly compared to weaving:

It was like spinning,

gathering air to the single strongest

thread.

In this simile, Lochhead likens the telling of a story to textiles. In her work the storyteller weaves a story out of her words, seemingly summoned out of thin air. The single strongest thread may refer to the most important feature of a story: its plot, perhaps, or the main character. In idiomatic ways the English language is already tuned to this simile: we say both ‘to spin a good yarn,’ meaning to tell a good story, and ‘following the thread’ of a narrative. Figuratively, it is easy to imagine a story as a single piece of cloth woven from different elements: plot, character, language, structure and so on.

Whatever her supposed day job, we can see that, by night, she becomes an incredible storyteller. You might need to use some inferencing on stanza 3 though, as the first few lines are a little difficult to decode. ‘Slander’ means to speak badly of someone and ‘shift’ can mean a shift at work; therefore slander her shiftless means to complain that she’s not doing any work (like grating corn husks or mending fabric). Never the one looks a bit like Scottish dialect, so unless you’re from the highlands you can understand it as ‘Never be the one’ to complain that she is not working. The storyteller has a couple of other jobs she’s meant to be doing, like cleaning. ‘Sloven’ means to be lazy and ‘spotless’ means that there is not even a spot left: in other words, she is sometimes lazy and sometimes hardworking. From dishwater or tasty was her soup we can infer that she also has to make the soup. At the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter whether her soup is good (tasty) or bad (dishwater) as the next line states clearly: to tell the stories was her work. I like the idea that, in this community, people are able to see that different skills and abilities are valuable and not everything has to be about productivity. The storyteller is valued for her storytelling abilities above anything else and people seem to appreciate this the most.

As the poem moves into the final stanza so night moves into day. Descriptions of the light are faint and weak, thin grey, as if the reality of the morning can’t compare with the vividness of the storytelling the night before. The way the light washes over the fields adopts the vocabulary of chores again. As the women build the fire and peasants’ feet feel around in the dark for their shoes, the diction reminds us that this is a world of subsistence living where work is never finished. Fricative F sounds are strong at the end of the poem: first, fire, feet felt, flat fields. F is a soft sound suiting the washed-out feel of this tepid grey morning. The line the stories dissolved in the whorl of the ear gives us an image of the stories vanishing. You may think this suggest that there is no place in the real world for the stories, that they are just a temporary relief from daily hardship.

However, following the poetic tradition of the volta or turn (a shift in perspective or thought occurring at the end of the poem), Lochhead steers you away from this thought, presenting instead her second figurative comparison. This ‘turn’ is signalled by white space surrounding the connective but they:

but they

hung themselves upside down

in the sleeping heads of the children

The image here is of bats sleeping in a cave. It suggests the stories are always present, but by day they are hidden out of sight. It is only when the daily work is done that the bats emerge and flew again in the storytellers night. Think closely about the word dissolved: when something is dissolved in a liquid, though it is transformed into an invisible state, it is not really gone.

The word ‘children’ suggests the true importance of the stories. Not only do they provide a measure of relief from the daily grind, but stories are also vessels for culture, traditions and values. In a time before electronic recording, and when many people (peasants) were unable to read and write, stories were an important method of passing knowledge and ideas on to the next generation. It seems to me that Lochhead purposely withheld mention of children until the end of her poem, so as to leave this idea hanging quietly in the mind of the reader like those figurative bats.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- For De Lawd by Lucille Clifton

I love the voice in this poem. Like Lochhead’s Storyteller, you can tell Clifton’s speaker holds the house together with her strong words.

- The Storyteller by Mike Jones

More a songwriter than a poet, nevertheless the lyrics to this song are certainly in the spirit of Lochhead’s Storyteller.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Storyteller at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

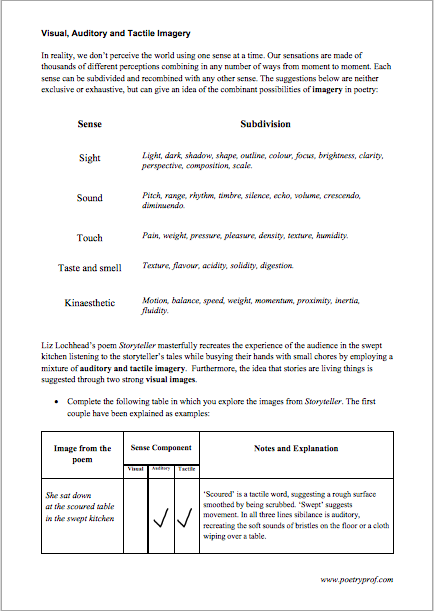

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining visual, auditory and tactile images.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Storyteller? What do you think of Liz Lochhead’s poem? What kind of images came to your mind when you read the descriptions of the community in the poem? Why not leave your thoughts, give us some feedback, or share your ideas in the comments section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.