Vachel Lindsay laments a vanished way of life.

“A wandering visionary who writes poems for and about the trees, birds, people, and unused country roads of America.”

Ian Winterbauer, (Vachel Lindsay Scholar)

The American buffalo, today known as bison, once roamed freely throughout North America in vast, shaggy herds. It will never be known just how many buffalo once covered the plains; estimates range between 30 and 75 million. Famous explorers Meriweather Lewis and William Clarke, who were tasked by President Jefferson to explore the lands to the west of the Mississippi River, wrote in 1806 about a herd they encountered grazing by the banks of a river in South Dakota: ‘the moving multitude darkened the whole plains.’ By the time Vachel Lindsay wrote today’s poem, the buffalo herds had already been decimated and the landscape was being changed. In The Flower-Fed Buffaloes, the disappearance of the buffalo herds stands in for the changes wrought on the American landscape – and culture – in the name of progress and modernisation. The plains Lindsay lived in and loved were vanishing, to be replaced by a new, brighter, sleeker – but not necessarily better – world:

The flower-fed buffaloes of the spring In the days of long ago, Ranged where the locomotives sing And the prairie flowers lie low:- The tossing, blooming, perfumed grass Is swept away by the wheat, Wheels and wheels and wheels spin by In the spring that still is sweet. But the flower-fed buffaloes of the spring Left us, long ago They gore no more, they bellow no more, They trundle round the hills no more:- With the Blackfeet, lying low, With the Pawnees, lying low, Lying low.

Lindsay wrote these words in or around 1926: but at the time of Lewis and Clarke’s expedition over a century before, the depletion of the buffalo herds was already underway, to protect the expansion of organised agriculture (wheat is mentioned in the poem). This eradication became more systematic throughout the nineteenth century, when an organised industry of hunters, skinners, butchers and tanners killed buffalo in their hundreds each day for hides and meat. History tells us the true purpose of this terrible holocaust: the eradication of the buffalo was intended as a way to destroy the livelihoods and culture of Native American people (the tribes Pawnee and Blackfoot are memorialised at the end of the poem) and ‘pacify’ the American frontier.

With this goal in mind, the railroad (locomotive) spread unimpeded across the plains, hastening the vanishing of the buffalo herds. Spooked by these strange and frightening metal ‘creatures’, buffalo would run beside the trains and passengers would shoot them out of the window. Hunting in this manner was advertised and encouraged by the railroad companies! By the end of the nineteenth century, out of those millions of buffalo who lived on the prairie, only 300 individuals remained. Writing years after their near-extinction, Vachel Lindsay’s poem can be read as an elegy, a memory of a memory of these magnificent, peaceful creatures and the native American cultures they symbolise.

Vachel Lindsay himself was something of an anachronism. Born in 1879 in Springfield, Illinois, his life crossed from the nineteenth into the twentieth century – the century of American urbanisation and industry. Millions of people moved from rural towns to America’s cities in order to pursue work and opportunity. Alongside this vast migration of working men and women, popular American culture – the literary scene, a brand-new movie industry, and emerging musical movements – all flourished in cities (like New York) teeming with creative people all yearning for new forms of artistic expression.

Lindsay stayed away.

Growing up in a small town in the American West, Lindsay felt much more at home in the wide-open spaces of the prairie than he did in the tightly packed streets of the booming cities. He wandered the land, like a medieval troubadour, becoming famous as a bard performing his poetry for live audiences in exchange for his bed and board, just as itinerant minstrels have done for hundreds of years. In 1912 Lindsay walked across America, tramping through Colorado and New Mexico, right at the frontiers of the American West; a weather-beaten copy of his poetry collection, aptly called Rhymes to be Traded for Bread, was his most precious possession. His performances were a kind of historical artefact, keeping poetry alive as an oral, spoken form in a time when more and more people were turning to the convenience of the printed word.

Lindsay’s poetry celebrated small town values in a time when urban concerns were dominating American culture and forcing other art forms to the margins. Musically inclined, he often accompanied his recitations with tambourines, drums and whistles and people paid good money to hear his impassioned recitations. Here lies Lindsay’s most important legacy. He is known today as a pioneer of modern singing poetry – poems that are meant to be heard, not read. Vachel said he wrote poems ‘for the inner ear’ and The Flower-fed Buffaloes gains an added dimension when spoken out loud. Close your eyes and listen to the poem – and you’ll be transported back to those days of long ago before the land was covered in a spiderweb of iron and steel, and any remaining traces of the flower-filled prairies were submerged under featureless oceans of corn.

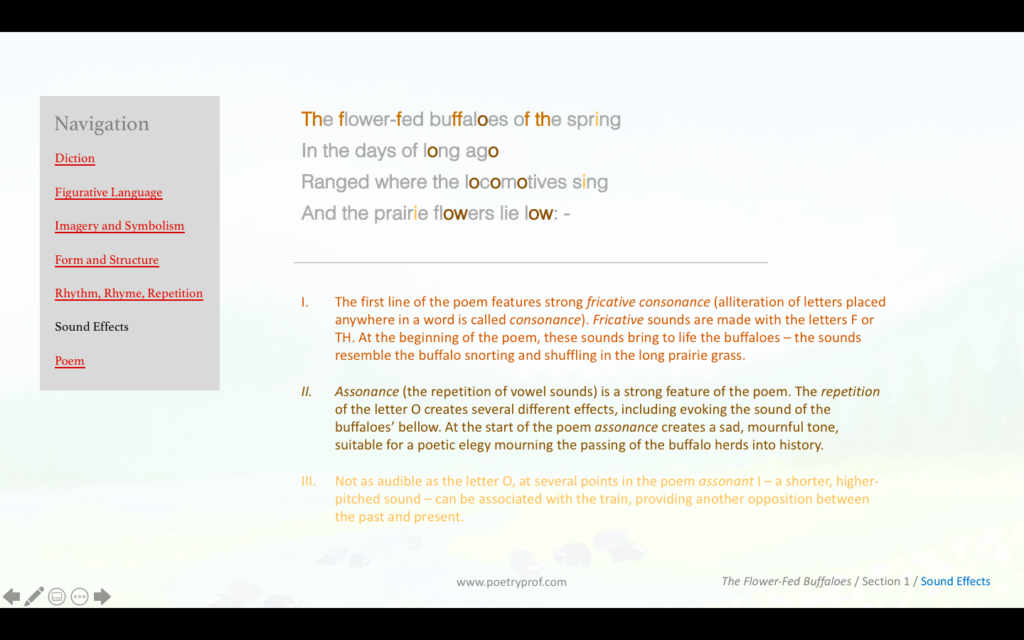

This magical transportation occurs in the very first line where we find ourselves amongst the flower-fed buffaloes of the spring. Fricative alliteration (made with the letters F and TH: the flower-fed buffaloes) surrounds us with the snorting and snuffling sounds of buffalo rooting for tasty flower buds in the long prairie grasses. You’ll hear those fricative sounds several times in the poem, primarily through repetition of the flower-fed buffaloes of the spring, but also in words such as left us and Blackfeet (a native American tribe who vanished alongside the buffalo, upon whom their nomadic lifestyle depended). There’s something amusing about the image of buffaloes – large, muscular creatures with coarse shaggy fur, thick sides, and even straggling beards – being sustained by something so small and delicate as flowers, although the image is also quite fitting. The buffalo were part of a flourishing ecosystem of plants and animals living in balance; before it was all swept away by the wheat, transforming diversity and colour into a bland monoculture.

I hope I’ve painted a vivid picture of American prairie scenery for you (check out this scene from the brilliant Dances With Wolves if you’re having trouble visualising). Perhaps because of the root word ‘image’ in imagery, we are predisposed to try to visualise images as ‘pictures’ in our minds. But our perception is built of more than sight: sounds, textures, movements, even tastes and smells interlace to form our experiences of the world. Poets like Vachel Lindsay know this, and their words seek to recreate ideas in ways beyond the visual. Images of this vanished world are evoked using words that suggest movement (tossing, blooming) and smell (blooming, perfumed). The picture in your mind shouldn’t be static, like a painting, but vibrant and alive – as if you could put out your hand and feel the grass waving against your palm, or cup your ear and hear the sounds of the wind, created using sibilance (tossing… grass again, and in the spring that still is sweet).

The harmony of this idyllic world is hinted at through the pleasing form of the poem: written in alternate lines of iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter (a traditional ballad form arrangement) and featuring solid, unambiguous rhymes, the poem sounds and feels like I imagine a contented buffalo might; solid, gentle, muscular, with a lolloping de-dum gallop and just a hint of mournful sadness in the timbre of its bellow. In fact, some of these features you might recognise as belonging to the sonnet form (rhyme scheme, iambic rhythm and a separation of the poem into two parts: the first eight lines is called the octave; the last six the sestet. Eagle-eyed readers will already have noticed that The Flower-Fed Buffaloes has fifteen lines, rather than the standard fourteen. There are precedents for this in the tradition of sonnets; sonnets of more than fourteen Iines are called stretched sonnets (or you might like to imagine the final line as an echo of the previous two, rather than a line in it’s own right). Just like the buffalo, as time passes the sonnet form becomes less and less tangible, as if it too is disappearing before our eyes. Take the rhyme scheme, for instance; a solid ABAB in the first four lines, then ABCB in the next, by the end of the poem any rhyming patterns have disappeared. I might be imagining things here, but – turn the poem on it’s side, squint a bit, and you can even discern the outline shape of a buffalo (broad flat back, four legs and tail, horns and wedge-shaped head) staring back at you from the page.

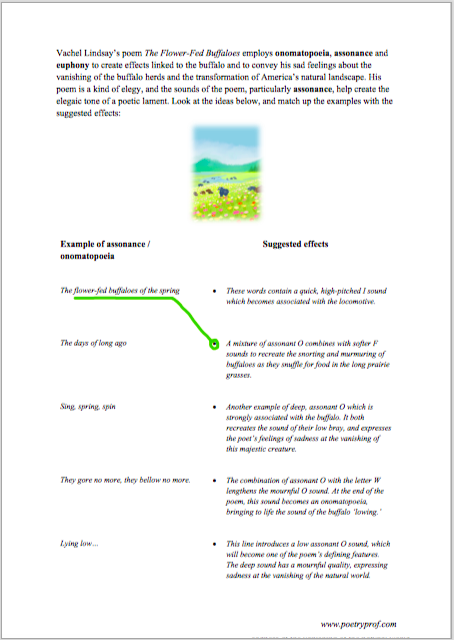

Of all the senses, we know Lindsay was most interested in sound; the defining effect of the poem is arguably assonance. Go back to the start and you’ll hear a deep, assonant O sound begin in the phrase days of long ago. From there it rumbles through the entire poem like the sound of an approaching buffalo herd: put your ear to the ground and you’ll hear it in the aforementioned tossing, blooming, perfumed. It’s in the line gore no more, bellow no more, where the boundary between assonance and onomatopoeia erodes and the sound resembles the buffalo’s cry. The poignancy of this forgotten sound is negated; no more is repeated three times (repetition at the end of clauses or lines of poetry is technically called epistrophe) to intensify the sense of loss. And, of course, the mournful O sound thrums powerfully at the end of the poem:

With the Blackfeet, lying low, With the Pawnees, lying low, Lying low.

For one brief, magical moment, Lindsay brings the ‘moving multitudes’ back from the dead, the sound of their mournful cries once more filling our ears as they trundle again around the South Dakota hills. Low is a polysemic word, meaning it has more than one assigned definition. On one hand it points to a physical position, lying low down in the ground, reminding us that any trace of the buffalo have long since vanished; any bones that weren’t boiled down for use in industry buried deep under the prairie soil and hidden by fields of wheat. But another meaning of the word low is ‘the characteristic deep sound made by cows’ (a usage which survives today in the well-known christmas carol Away in a Manger: ‘the cattle are lowing, the baby awakes’). The end of the poem fills our ears with the sounds of the buffalo bellow, an outpouring of emotion that not only laments the passing of these majestic animals, but also the Blackfeet and Pawnee tribes, human cultures whose fate was tied to the buffalo.

If the flower-fed buffalo symbolises a vanished past, the progress of modernity is represented by an equal and opposite symbol: the locomotive. One of the most interesting and challenging aspects of the poem is the way these two symbols overlap. As Lindsay eulogises the vanished buffalo herds and laments the genocide of Native American tribes, we might expect him to present the train negatively. Instead we get a very subtle treatment of the idea of progress: the first instance of this is in the third line where the locomotives sing, a personification that almost romanticises the railroad. Involuntarily, images of moustachioed, behandkerchiefed train drivers happily letting off steam come to mind – full rhymes (spring / sing; ago / low) play their part here too, as word pairs create pleasant harmony. Later, we see the trains speed across the landscape as wheels and wheels and wheels spin by. This line is open to interpretation: on one hand repetition evokes the tentacular spread of the railroads and the sad extent to which urban and industrial forces have come to dominate the natural world; but, on the other hand, the sounds of the line (W and L blend naturally; sibilant S makes a happy companion) are soft and pleasing. The same is true for wheat, another symbol of progress, where the phrase swept away by the wheat blends similar liquid and sibilant sounds. Liquid is a category of alliteration (or, when letters repeat within words as well as at the beginning of words, consonance) made with the letters W, L and R. It is especially good at suggesting a flowing motion; either literal when it comes to movement (of buffalo, train, or wind) or figurative in the ideas of progress and modernity ‘sweeping’ across the country. Frequent enjambment (lines of poetry that run one into the next with no break, pause or punctuation) suggests similar ideas.

Far from being oppositions in the poem, then, the relationship between the buffalo and train is almost interchangeable. Nowhere is this more apparent than when Lindsay describes the way the buffalo trundle round the hills no more – as if they are a natural precursor to the coming of the train. The word trundle can be explicitly used in the context of trains – so Lindsay’s use of diction seems to transform the buffalo into the train. What a brilliant and poignant way of implying the locomotive’s prominent role in the death of the buffalo, akin to that technique used in films where a scene from the past blurs and fades into a scene from the present.

Ironically, Lindsay was to suffer a similar fate to the buffalo when his art was swept aside by the same forces of progress and modernity that had wreaked havoc on the prairie. By the end of the 1920s, Lindsay had passed into relative obscurity. His musical stylings, his love of oratory and dance, his experimental readings all belonged to a past era. Tastes changed – and the future of American poetry was becoming bound to the printed page. Due to the performative nature of his work and his brief fame as a wandering troubadour, when Lindsay died so did knowledge of his work. People paid to see his act; to his dismay his audiences were less interested in what he had to say than how he said it. Fortunately, literary criticism has unearthed some of Lindsay’s treasures; he can be appreciated today as a man who carved out his own little sanctuary amidst the turmoil of change, preserving oral traditions that might otherwise have been forgotten, along with the bones of his beloved buffalo, in the days of long ago.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Bull Moose by Alden Nowland

Like Lindsay, Nowlan is interested our relationship with the natural world. In this magnificent and tragic poem, an old bull moose, once king of the savannah, wanders into town where he is confronted by different people: some kind, some cruel, some curious. The results are predictably heartbreaking.

- To the Driving Cloud by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Famous for The Song Of Hiawatha, Longfellow was a student and professor of European languages who had an abiding interest in America’s indigenous peoples. In this poem, he imagines a Native American chieftain walking through the streets of a modern American city, questioning the walls and pavements. The buffalo gets an honourable mention towards the end of the poem.

- The Mountain Chant (a traditional Navajo incantation)

Worthy as poets like Lindsay and Longfellow are in documenting the lives and lamenting the loss of Native American cultures, it’s still history narrated by the white man. So you should definitely not miss this Navajo chant, addressed to a god, and featuring the kinds of repetitions and rhythms that are best appreciated when heard read aloud.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Flower-fed Buffaloes at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining assonance and onomatopoeia.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap lesson.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you like this analysis of Vachel Lindsay’s poem? Do you agree that the shape of a bull appears when you turn the poem sideways? What techniques have you spotted that are missing from this breakdown? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Hey Poetry Prof! Love your work. Is there anyway I can contact you about some of your bundles or about poems you’re planning to create resources on in the future? Thanks!

Hi,

I’m glad you enjoy the site. You can contact me by clicking on my profile link.

Very well done. Have you done other work on Lindsay?

Hi Peter,

I’m glad you liked this post. I very much enjoyed researching Vachel Lindsay. He’s quite niche over in the UK (which is where I’m from) and I didn’t know much beyond this poem. I hope to encounter more in the future.

Hi