Kofi Awoonor summons his oral heritage in this mournful poetic lament.

“A writer, politician and traditionalist with great wit.”

John Mahama, Ghanaian President (2012 – 2017)

Kofi Awoonor was born in Ghana in 1935 and lived an eventful life, during which he was a writer, poet, professor, critic, ambassador to Brazil, and later, a UN ambassador – he even served time in jail after being arrested for his part in a coup; he wrote about this experience in his book The House By the Sea. He was imprisoned without trial and later released without charge. Knowing this, when reading The Sea Eats the Land at Home, it’s hard to escape the idea that he may have been marked by being a victim in such events; in particular the poem shows the way that one’s life can be so easily disrupted – even ruined and destroyed – by forces beyond the control of ordinary people. (In a cruel irony, Awoonor was killed in 2013 in a bomb attack at a shopping center in Nairobi, Kenya.)

At home the sea is in the town, Running in and out of the cooking places, Collecting the firewood from the hearths And sending it back at night; The sea eats the land at home. It came one day at the dead of night, Destroying the cement walls, And carried away the fowls, The cooking-pots and the ladles, The sea eats the land at home; It is a sad thing to hear the wails, And the mourning shouts of the women, Calling on all the gods they worship, To protect them from the angry sea. Aku stood outside where her cooking-pot stood, With her two children shivering from the cold, Her hands on her breasts, Weeping mournfully. Her ancestors have neglected her, Her gods have deserted her, It was a cold Sunday morning, The storm was raging, Goats and fowls were struggling in the water, The angry water of the cruel sea; The lap-lapping of the bark water at the shore, And above the sobs and the deep and low moans, Was the eternal hum of the living sea. It has taken away their belongings Adena has lost the trinkets which Were her dowry and her joy, In the sea that eats the land at home, Eats the whole land at home.

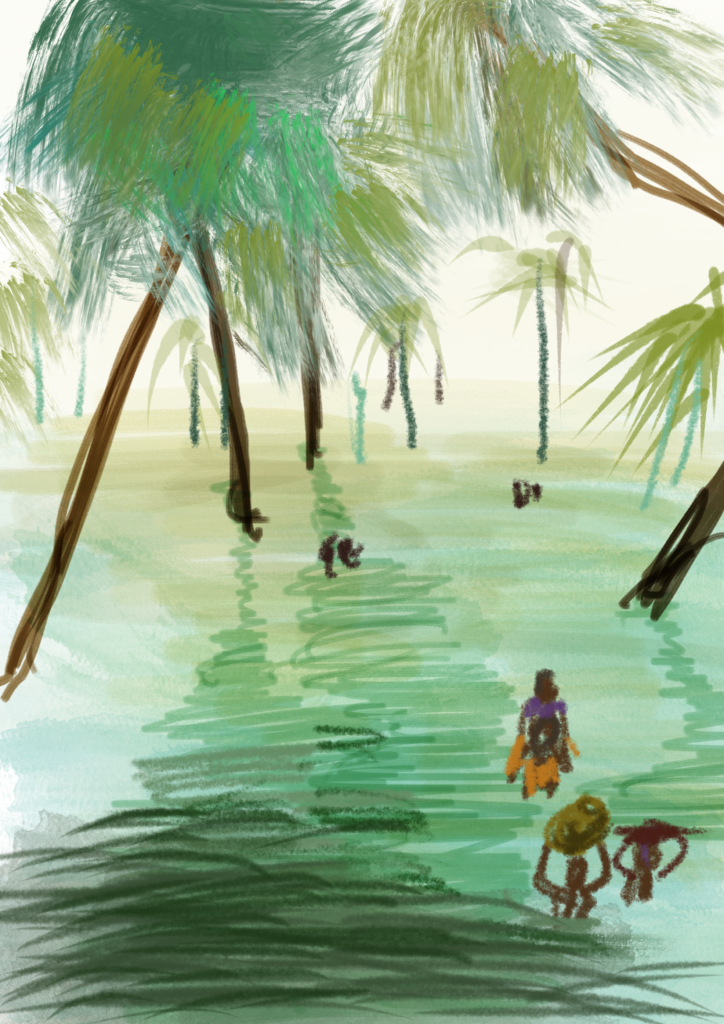

Given the events of his life, it’s easy to understand how the sea represents huge, inevitable and unstoppable forces – forces of nature, fate, national politics, even war – that, like floodwater, sweep in and disrupt the lives of the townspeople. In 1935, Ghana was still under British colonial rule, and as you read through the poem ask yourself whether the sea acts like a colonial ruler, taking without concern for the lives of Ghanaian people. The opening words of the poem, at home, suggest the speaker is elsewhere and is looking back at his native land from afar. In this poem, people are reduced to bystanders – emphasised by the repetition of stood in line 15 – unable to prevent the destruction and thievery of the sea, abandoned even by their gods, who are silent and also unable, or unwilling, to intervene. One townswoman, Adena, is lucky, she loses only a few trinkets (though these would, of course, have important value to her); Aku is not so lucky – she has lost her cooking pot (symbolic of warmth and nourishment) and the sea has stranded her and her two children in the cold – look how they are left shivering. Through juxtaposing the two women and their plight, Awoonor suggests that the destruction wrought is both indiscriminate and arbitrary: no one in the town is safe, and no one can know what will be gone when the ‘flood’ recedes.

The most important device that supports this reading of the poem is personification. The sea is (apart from a brief section in lines 21-25) never described as having the qualities of water. Rather, it is given human traits – cruelty, anger, spite. It runs like a person, collects firewood, and ‘carries away’ livestock as a person would do. When you read It came one day at the dead of night it’s like the sea has the ability to decide for itself when to come, knowing when the townspeople will be most vulnerable. This effect is most obvious when Awoonor describes it as a living sea– it’s like he’s deliberately pointing out to the reader that the sea is a figurative device. What it precisely stands for is left vague, although (because the people in the poem are women, and the sea causes mourning shouts of women, sobs… and low moans) one might characterise the sea as masculine – a brutal raider, maybe, or a party of thieves intent on destruction.

The repeated line The sea eats the land at home acts as the poem’s refrain and deserves a closer look. The key word is eats. On one level it simply continues the personification. On a thematic level it strikes a chord as eat suggests swallowing and consumption. The idea of the land being swallowed by an implacable force is disturbing. At the end of the poem the refrain is altered slightly to read Eats the whole land at home. The change is a tiny surprise and our attention is caught by the alteration; whole. The appetite of the sea is insatiable, it doesn’t stop until it has devoured everything there is to eat – and even then it seems like it’s still hungry. A town with no homes left leads us to think of the displacement of people, forced migration and refugees from disaster. If you are reading the poem as a critique of colonialism, cooking-pots, ladles, trinkets and other things become symbolic of an entire culture washed away by the colonial invaders.

So what about that short section straight after It was a cold Sunday morning? Briefly, the sea really does become watery:

The storm was raging,

Goats and fowls were struggling in the water,

The angry water of the cruel sea;

The lap-lapping of the bark water at the shore,

The form of the poem is free verse, which means the writer can arrange the words in each line to suit his own purpose. Let’s look carefully at the first couple of verses. Do you notice the position of the verb in each line? – it’s always near the start: running, collecting, sending, destroying, carried, eats. When you read out loud, putting a slight emphasis on these verbs creates a rhythm reminiscent of waves climbing the shore. This effect works in tandem with alliteration – liquid sounds dominate: L in collecting, land and places; R in running and hearth; W in town and firewood. Words beginning with ‘W’ are particularly prominent in lines 11 to 13: wails, women and worship come in quick succession and weeping follows in line 18. Later in the poem the liquid combination of W and R is unmistakeable – try reading the line which were her dowry and her joy seven times as fast as you can!

In many reproductions, the poem is printed in a single unbroken stanza (called continuous form). From beginning to end there are only five full stops, so most of the lines are connected by enjambment. As you read, your eye flows easily from one line to the next. There is no internal punctuation in any line, so this flow is never interrupted. In other words, the lines of the poem move like water, flowing easily from one to the next and – in this section – completely overwhelming the town. The image of goats and animals drowning is quite horrific: it’s like the flood that God sends to wipe out mankind in the story of Noah. Another biblical allusion is to the story of Ninevah; God sends a flood to wipe out the city when the inhabitants become too sinful. This is the story in which Jonah is swallowed by the whale, which reminds me of the way the sea eats the town. Then, suddenly, the water recedes and we’re left with the lap-lapping of the bark water at the shore. Look carefully at the punctuation in this section: see the semi-colon? Notice how the water calms and quietens in the last line. Words like raging, storm, angry and cruel are replaced by the softly onomatopoeic lap-lapping. It’s like the flood waters rose and rose – then receded to the distance… at least for a while. I get the sense they’ll return soon.

Additionally, the form of the poem echoes the literary context in which Awoonor writes. His grandmother was an Ewe dirge singer, and his poetry can be seen to mimic the form of this oral tradition. You can hear the voice of the traditional singers in the repetitions of the poem, which sound like a mournful refrain. The first verse introduces strong assonant sound patterns that resonate like a deep bass voice through the poem. Long ‘E’ sounds in sea, eats, hearth and ‘O’ sounds in firewood, cooking, fowl, town are joined in the second verse by long ‘A’ sounds in day, away and ladle. The shortest line in the poem, weeping mournfully, is all assonance. Partly due to the repetition of land at home nasal sounds strengthen the sense of an audible voice. Techniques we have noted before – few full stops, enjambment, continuous form– also point to Awoonor’s Ewe oral heritage. As these techniques also serve to mimic the flow of water, this is one of those happy times when form and content are matched perfectly by the writer’s use of language.

It seems that Awoonor wants us to think of the sea both literally and figuratively at the same time. He doesn’t just want this poem to be about him, or about one particular town. The huge forces that disrupt all our lives can take many forms. For him it was political; he was arrested for his alleged part in a coup, a charge that was never proven. For other people life may be ruined by a flood that destroys a home, like what happens to Aku. Yet others may be the victim of a burglary in the night that steals away precious jewellery, which happens to Adena. Awoonor chose the metaphor of the sea because the flood of sea water can suggest the nature of many other terrible forces: it’s unstoppable, destructive, all-consuming. An important description is: the eternal hum of the living sea. Hum can be read quite callously, as if the sea is humming along happily as it commits terrible atrocities. Eternal is crucial to understanding Awoonor’s belief: the huge forces that can interrupt our lives at any moment are ‘eternal’, they will always be there no matter what – so living with the threat of destruction and ruin is an inescapable part of the human condition.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The First Circle by Kofi Awoonor

In this powerful imagist poem, Awoonor describes life from inside a jail cell and alludes to the treatment he received when arrested and imprisoned, without trial, for his supposed involvement in a coup. He was later released without charge.

- Coffee Break by Kwame Dawes

Awoonor’s nephew, Dawes has been described as ‘the busiest man in literature’. Ghanaian by birth, Jamaican by choice, Dawes, like Awoonor, wears many hats: poet, playwright, novelist, editor, critic, musician and professor. Read this poem to the end and be blown away by what you thought was just a simple story of making a cup of coffee…

- As I Ebb’d with the Ocean of Life by Walt Whitman

Like Awoonor in The Sea Eats the Land at Home, Whitman employs structural techniques – in particular: enjambment; alliteration; anaphora – throughout his poem to conjure a powerful impression of the ocean’s presence in the mind of a speaker looking back over his life. The way he blends the imagined swell of the ocean with the ebb and flow of perception and memory is beautiful.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Sea Eats the Land at Home at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to download our bespoke study bundle for this poem. The bundle costs £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on the personification of the sea in Kofi Awoonor’s poem.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap activity or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy Awoonor’s poem? Who or what do you think the sea represents? Can you recommend any similar poems you think readers might like? Ask a question, give an opinion, leave a comment in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

This is the best analysis I saw about this poem!

Hi Savithri,

Thank you so much for your compliment. It’s so nice to get positive feedback, it makes our work worthwhile :o) Hope to see you on the blog again. Best wishes…

I love your analysis. This poem is a true happening of where he comes from in Ghana.

I was just looking for the poem because the tidal waves have hit the coastal towns in Ketu-South Eastern Ghana again and the people are devastated.

Same here. very disturbing.