Anne Stevenson’s philosophical poem asks what it means to be truly alive.

“Stevenson’s accomplishments as a poet are nothing short of vast”

Jay Parini writing in Anne’s obituary, 2020

Today’s philosophical poem was probably inspired by Anne Stevenson’s own experiences being a mother several times over. Her daughter, conceived with her first husband, was born in 1957 and she had two sons with her second husband in 1966 and 1967. The collection of poetry called Reversals, from which The Spirit is too Blunt an Instrument is drawn, was published in 1969. It’s easy to imagine Stevenson all those years ago holding her new-born children and marvelling at the miracle of creation. She uses this perspective to write through the eyes of a new mother observing her baby carefully; the more wonderful the baby appears, the more the mother doubts how such perfect little bodies can ever be created by the clumsy hands of human beings guided by all their awkward anxieties and emotions.

The spirit is too blunt an instrument to have made this baby. Nothing so unskilful as human passions could have managed the intricate exacting particulars: the tiny blind bones with their manipulating tendons, the knee and the knucklebones, the resilient fine meshings of ganglia and vertebrae, the chain of the difficult spine. Observe the distinct eyelashes and sharp crescent fingernails; the shell-like complexity of the ear, with its firm involutions concentric in miniature to minute ossicles. Imagine the infinitesimal capillaries, the flawless connections of the lungs, the invisible neural filaments through which the completed body already answers to the brain. Then name any passion or sentiment possessed of the simplest accuracy. No, no desire or affection could have done with practice what habit has done perfectly, indifferently, through the body’s ignorant precision. It is left to the vagaries of the mind to invent love and despair and anxiety and their pain.

The opening lines of the poem present a fundamental opposition inherent to human beings: the mind verses the body. Stevenson first observes her baby as a physical creature, like a statue sculpted by some fantastically gifted artisan. But people are more than lumps of beautifully shaped clay; something incorporeal animates our bodies, giving us emotions, consciousness, sentience, and feelings. Stevenson refers to this abstract, incorporeal essence variously as our spirit, passion, sentiment, desire, affection, and finally the mind. Where the poem is quite unusual is in its reversal of our expectations. Being such clever creatures, we often think that our abstract mind is the most refined and elegant part of ourselves. Yet in Stevenson’s poem, it is the body that is complex and intricate whereas our inner selves are described as blunt, meaning imprecise, clumsy, messy and awkward. She sets out this metaphor in the first two lines and reiterates it in the next three, replacing the word mind with passions and blunt with unskilful. Holding the new-born babe in her arms, Stevenson finds it hard to believe that the act of creation could have been guided by the hand of anything as clumsy and unskilful as a human being, controlled as we are by all our messy feelings and emotions.

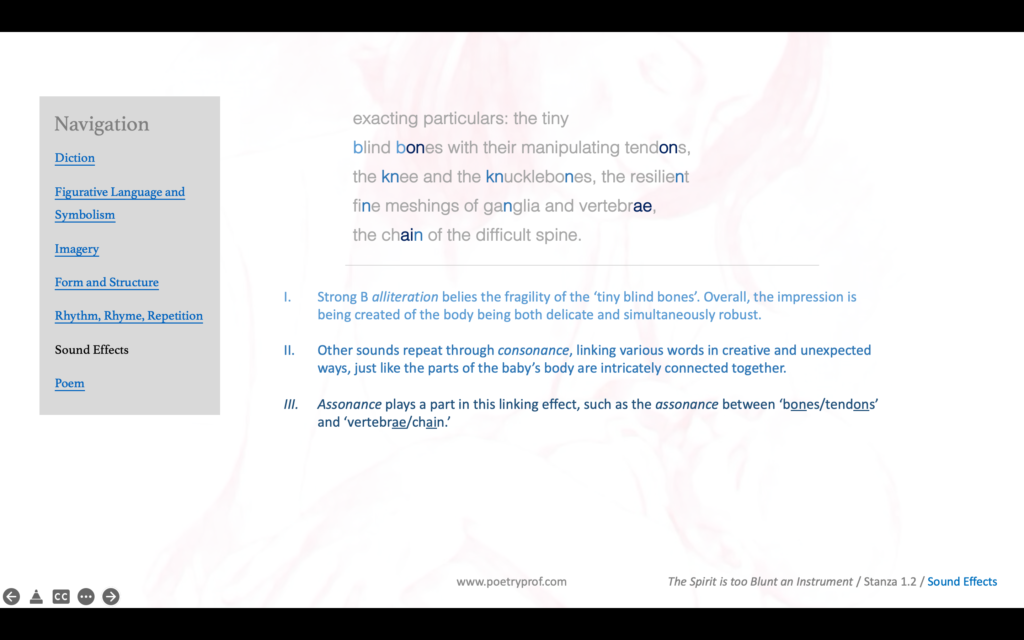

To evoke the contrast between our body and mind, Stevenson employs two kinds of diction in her poem: concrete and abstract. Concrete words are rooted firmly in the tangible, physical world of things, objects, sounds, and so on, that can be perceived by the senses. Abstract words describe intangibles: emotions, thoughts, feelings and concepts. Concrete words tend to be more specific and precise, whereas abstracts tend to be a little fuzzy. For example, we can probably all agree what a baby looks like, broadly speaking. But if I ask two people to draw passions or sentiments, I’m likely to get two very different depictions of the same word. It is Stevenson’s masterful employment of concrete diction throughout the first two stanzas that gives her baby’s body such a precise, tangible, real and robust feeling. Choose almost any noun from between lines six to eighteen, where her gaze explores the baby’s body, and it’s likely to be a concrete word: bones, tendons, knee, knucklebones, ganglia, vertebrae spine, eyelashes, fingernails, ear, ossicles, capillaries, lungs, neural filaments, and brain are all concrete words from stanzas one and two.

The images she forms for us are of the body as a kind of precisely engineered machine, wonderfully complex, intricate and finely detailed. From lines six to nine, the mother’s gaze traces the outline of the baby’s skeleton, the framework upon which everything hangs: bones; the knee, knucklebones and the spine. Underlying her observations is a sense of wonder at the delicacy and robustness of the body, it is both finely crafted and incredibly tough at the same time. The bones themselves are hard and unyielding, an idea expressed through hard, solid alliteration (blind bones) but the fine meshings and manipulating tendons that connect the bones one to another are pliant and supple. At times Stevenson employs juxtaposition and almost-oxymorons to suggest the way the body seems both durable and fragile: the word resilient at the end of line seven is immediately followed by the word fine at the start of the next line. These contrasts persist through stanza two, where eyelashes, fingernails and ossicles (tiny bones inside the ear) are incredibly fragile yet are described as firm and sharp.

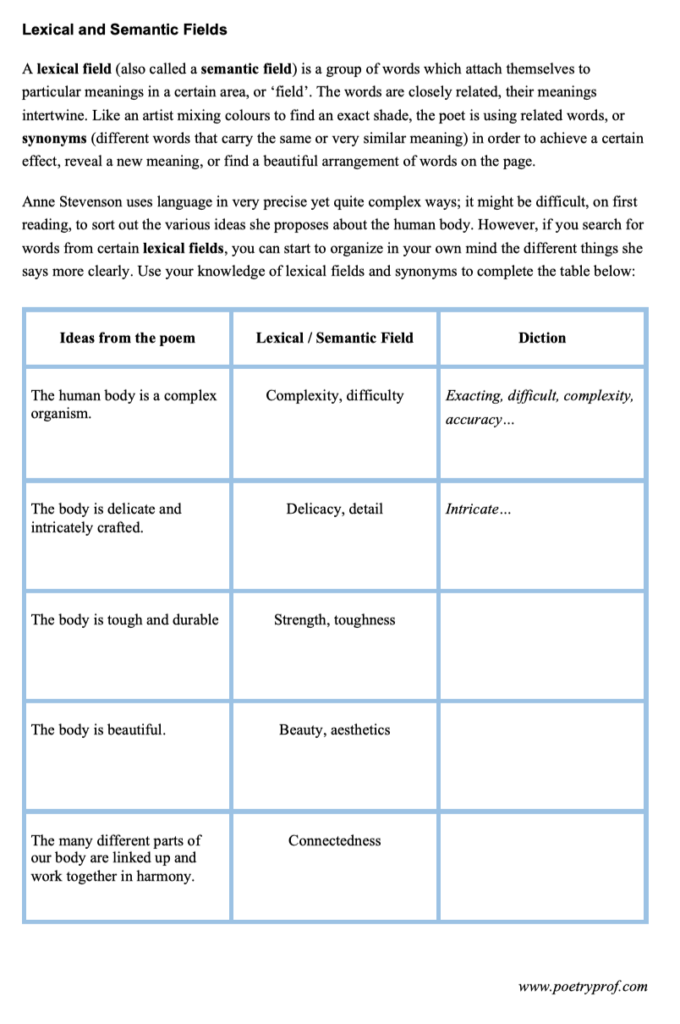

While the lexical density of this poem might be challenging on first read, searching for words which are related to each other in meaning can help you organise your thoughts about The Spirit is too Blunt an Instrument. Words from the lexical fields of ‘intricacy’ and ‘complexity’ help evoke the impression of our bodies as precise and complex objects. This theme emerges in line four through use of the word intricate ; words with similar meanings include: tiny, fine, difficult, distinct, complexity, miniature, minute, precision, and accuracy. As the poem unfolds, Stevenson’s observations seem to become finer and ever more delicate, until she envisages even the tiniest invisible neural filaments of the brain, which are so finely detailed as to be beyond our capacity to even perceive with the eye. Once again, unusual juxtapositions help convey an impression of wonder at the body’s complexity: the word intricate is immediately followed by exacting, which means ‘a challenge to one’s skill or ability’. No matter how complex the poem may seem, the words and ideas in the first two verses always loop back to the poem’s central assertion: the creation of such a deftly detailed body is beyond (too exacting for) the mind/spirit’s imprecise clumsiness.

The ear is a particularly important feature on which the mother’s gaze lingers. The ear is described as shell-like and concentric, words that imply circular shapes which draw her gaze like a whirlpool draws water, spiralling and spinning inwards. The ear forms a kind of portal, allowing her gaze to travel even deeper into her baby’s body, giving her access to some of its hidden secrets like the capillaries and lungs. Key to this ‘spiralling’ effect is the word involution, which literally means ‘enfolding’ and is used here to express the way the inner ear seems to sit inside the outer ear, almost like Russian dolls sitting one inside the other. The juxtaposition of miniature to minute helps too, as these two words are so similar one seems to be a condensed, shrunken version of the other.

Like a Swiss clockmaker appreciating the complex workings of a handheld watch, Stevenson increasingly marvels at the way the body is not just complex, tough, finely detailed and intricate, but how all the tiny parts synchronise together in perfect harmony. She notices some of our connecting tissues and employs diction that implies ‘interconnectedness’: tendons, meshings, chain, flawless connections. One word that stands out is ganglia, which are fibrous structures that can be found all over the body, including the brain. Each ganglia is a nexus point containing a bunch of nerves and synapses, meaning this word expresses much of what Stevenson is implying about the body: it’s a collection of tiny parts that work together instinctively. All this builds to her observation at the end of verse two that everything is automatically connected: the completed body already answers to the brain. Later, Stevenson will use the word habit to reiterate the idea that the body has an instinctive, biological ‘knowledge’ of how to operate that is independent from any messy human intention.

‘Interconnectedness’ is also the magic ingredient in Stevenson’s poetry. Just as the body is more than the sum of its parts, her poem is more than just a random collection of words. While the poem isn’t written in any set form, there are nevertheless formal and structural features that, like those blind bones and invisible filaments, are hard to see; yet they link the parts of the poem together like that semi-transluscent skeleton under the baby’s skin. Most obviously, despite having no set meter or rhyme scheme, each verse of the poem contains exactly nine lines, albeit of varying lengths. Stevenson connects each line to another using copious enjambment, by which one line of poetry runs into the next with no discernible break or pause. I hardly need give an example; as the stanzas are written in only a couple of sentences each, it’s almost impossible for the words not to flow from line to line. Within these sentences, punctuation is deployed extremely precisely, so that when held at arms’ length the first two stanzas form a visual mirror of one another, like left and right hands. In stanza one, Stevenson uses a colon to create a caesura (strong pause) in the middle of line five. And there, in stanza two, line five, you can find another caesura (this time made by a full stop). Even the third stanza breaks in line five, where two commas isolate the word indifferently to form another caesura.

Initially a student of music, Anne Stevenson was encouraged to pursue writing instead by one of her tutors. Nevertheless, it’s safe to say that music and musical influences still run through her poetry. Even after she started to fall deaf, she insisted that her poems began with sounds and rhythms rather than words. In 2007 she wrote: “Although I rarely write in set forms now, poems still come to me as tunes in the head. Words fall into rhythms before they make sense.” That’s why I think it’s less important to know precisely what all the difficult words in this poem mean, than to be sensitive to how they sound when read out loud, almost like an arranged musical composition. Anne plays with alliteration, consonance, assonance and subtle near-rhymes almost constantly, so that words and parts of words seem to ‘click’ together like pieces in a puzzle. Obvious repetitions (such as blind bones and knucklebones) mesh with slightly less obvious almost-rhymes (try miniature/minute or tiny/spine) to fairly outlandish patterns of alliteration and consonance (alliteration is the repetition of letters at the beginning of words; consonance is the repeated occurrence of letters anywhere in words): for instance, the phrase intricate exacting particulars contains a series of repeated clicks and clacks, especially hard C and T, but also the letters R and assonant I. You could throw a dart and it’ll probably hit an alliteration, consonance or assonance hidden somewhere in the poem: blunt/baby, blind/bones, knee/knuckle, complexity/completed, already/answers, passion/possessed, practice/perfectly – I’m sure you can find more. Stevenson plays with the arrangement of words on the page, scattering sounds around and allowing her natural sense of music to surreptitiously fit words together. Sonic connections even link the three verses of her poem together; the rhyming words instrument, crescent, sentiment and chain, brain, pain are all deliberately positioned in the first and last lines of each verse. All in all, the sounds of the poem support the idea of intricate, invisible connections that Stevenson imagines holding all of us together in quite miraculous fashion.

Because the body appears to her as a technical marvel, it so follows that many of her words are technical words, drawn from the lexical field of biology or science: tendons, vertebrae, ganglia, ossicles, capillaries, neural, filaments are all words drawn from the scientific study of anatomy. Again, I don’t think it’s crucial for you to know exactly what a ganglia is, or where precisely the ossicle bones are. What is more important is being sensitive to the tone the words create; as the body seems such a precise, finely tuned machine, so Stevenson’s use of words is precise, clinical, and exact. If you are put off by this technical diction, finding it a little cold and uninspiring, well… that’s kind of the point. In stanza three, Stevenson admits that the body is also ignorant, indifferent and acts out of mere habit, three cold and unfeeling words. While the body is a miracle of engineering, we are, at the end of day, not blank and empty machines. The spirit may be a blunt instrument, but it’s ultimately the spirit that injects our bodies with that spark of life, all those messy feelings, vague emotions and abstract thoughts and ideas that make life such a difficult – but incredible – journey.

That’s why, brilliantly, once the poem reaches stanza three and Stevenson acknowledges the mind’s contribution to our state of being, she entirely shifts her choice of diction from concrete to abstract words: passion, sentiment, desire, affection, love, despair, anxiety, pain are all abstract concepts, feelings, and emotions. She knows that, because our emotions are more complicated than straightforward flesh and bones, life isn’t always rosy – her baby will know anxiety and pain as well as love. Here’s where the mind, with all its vagaries (meaning things that are unclear or difficult to understand) is so important. We are not machines produced in a factory but individuals, more like masterpiece works of art, each one unique. And it’s our passions, desires, and affections that make us so, not our bodies.

Even here, at the end, Anne can’t stop playing with structural features that imply connection – but now that sense of connectedness includes the mind, spirit and emotion as well. The last three lines are basically a straightforward list of emotions, love and despair and anxieties and their pain, but they all spill out in a rush of feeling that you might think has been lacking in the poem up until now. Don’t underestimate the contribution of the little word and in these lines. Using the word and to connect items in a list is a technique called polysyndeton – it’s this that gives the end of the poem that euphoric ‘rushing’ feeling, as if she’s finally releasing all the emotions being stored up to now. Life can sometimes be a bit of an emotional rollercoaster, and the end of the poem suggests the mother can foresee some of the ups and downs her baby will experience as she grows up.

Stevenson ends as she began, by acknowledging the messiness of the human spirit, but now with a sense that she appreciates the important role the vagaries of the mind play in guiding the act of creation. Despair and anxiety are inescapable parts of life, and pain is the price we pay for love.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- False Flowers by Anne Stevenson

For something very different by the same writer, try this acerbic poem about a thoughtless gift bought in a rush. You can hear Anne’s distinctive love of music running through these lines as well.

- I Know a Baby, Such a Baby by Christina Rosetti

Much more sentimental and mawkish than Stevenson’s poem, this is possibly one of the most famous baby poems ever written.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Spirit is too Blunt an Instrument at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining lexical fields and how they are used in this poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Anne Stevenson’s poem? What are your thoughts about the relationship of body to mind in this poem? Can you find more ‘hidden connections’? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

How is “miniature to minute” a juxtapose each other because miniature means a thing that is much smaller than normal and minute means something extremely small.

How does “miniature to minute” juxtapose*