Rosemary Dobson’s unique backwards-poem reminds us that, however much we might want to, we can’t change the past.

“… a poet who could take the reader beyond the immediate image to another insight.”

Peter Kirkpatrick (Professor of Australian Literature, University of Sydney)

Rosemary Dobson was a twentieth century Australian poet, perhaps most famous for her ekphrastic poetry (ekphrastic poems are poems about other works of art, such as paintings or sculptures) about a series of European artworks. She studied at Sydney University (although not English Literature, showing you don’t have to be an expert to be an amazing writer) and her first collection of poetry, called In A Convex Mirror was published in 1944. Dobson’s hallmark was employing traditional forms, but making small and subtle alterations, loosening the poems into more unique and unconventional shapes. You will undoubtedly recognise this talent at play in today’s poem:

At the instant of drowning he invoked the three sisters.

It was a mistake, an aberration, to cry out for

Life everlasting.

He came up like a cork and back to the river-bank,

Put on his clothes in reverse order,

Returned to the house.

He suffered the enormous agonies of passion

Writing poems from the end backwards,

Brushing away tears that had not yet fallen.

Loving her wildly as the day regressed towards morning

He watched her swinging in the garden, growing younger,

Bare-foot, straw-hatted.

And when she was gone and the house and the swing and daylight

There was an instant’s pause before it began all over,

The reel unrolling towards the river.

Anyone who’s read Martin Amis’ novel Times’ Arrow – set in a universe where time is contracting – or F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (in which a man is born old-aged and lives his life in reverse) will be ‘aah-ing’ in recognition at the way today’s poem by Rosemary Dobson unfolds: from the end backwards. We see a man drowning in a river; at the moment of his death he suddenly bobs back up to the surface, puts on his clothes and returns to his house. All this plays out like a film rewinding from end to beginning. We get an impression of the life the man lived before this fateful day: we see him writing, crying, loving, all in reverse chronological order. Finally, the scene fades away… before the whole thing plays out again from the start. In this novel way, the poem doesn’t so much tell the story of a man’s life, rather gives us snapshots, as if we’re flicking through a photo album from back-to-front. This idea is made explicit in the final line of the poem, which gives us the metaphor of life like a movie or a photo album: as a reel – a series of images – unrolling towards its end.

The title of the poem is the key to unlocking its mystery. The Three Fates – known in Greek mythology as the Moirai – are female goddesses who control the destinies of mortal men. In many depictions, these women are configured as weavers, spinning the tapestry of time, with mortal lives as threads, each with its own predetermined past, present and future. The individual names of the Moirai illustrate this metaphor: Lachesis allotted the cloth and set the pattern; Clotho was the chief spinner; Atropos used her shears to cut the cloth into its final shape.

Over time there have been many different iterations of The Three Fates, and in Dobson’s poem we don’t see them weaving or spinning. Other versions of the story have them reading or writing the book of Fate, and it is this idea that the poem takes as its central concern. An unnamed man, at the moment of his death by drowning, in desperation calls upon the Three Fates (demystified in the poem itself as three sisters) to rescue him. They answer his call, but – in the capricious way human wishes always seem to be granted – pervert his salvation into a terrible curse. He is given a second – and third and more – chance to relive his life, but backwards. In this way the power of fate over mortal lives is asserted: the man cannot change the past, cannot rewrite his story (we see him return to the same house, futilely set down the same lines of poetry, endure the same loneliness time after time) or alter the woven pattern of his life. Instead he is forced to watch in despair, a helpless prisoner in his own body, as his life’s events are played out in identical fashion over and over again. Understanding how allusion works is important here. Dobson’s poem alludes to the three fates through the title, but in the poem itself the fates are personified as three sisters. Whether the sisters are real, or simply Dobson’s iteration of the mythological fates is ambiguous. One idea that holds water is that they could be related to the girl we meet later in the poem. If so, we might ask what did the man do that made them want to lay such a horrific curse upon him?

The set-up of the poem is realised in stanza one, which isolates the first line using a full stop. From this event, the rest of the poem unspools:

At the instant of drowning he invoked the three sisters.

The diction of this stanza is a little odd, both invoked and aberration are elevated, hearkening back to the mythological origins of the poem. The word aberration is a synonym for mistake: it leaves the reader in no doubt that life everlasting is no blessing, but a curse, as the man is forced to relive the same mistakes over and over, with no power to rectify what went wrong the first time around. Later on, the idea that man is powerless to affect his own fate is presented in a much more straightforward way: he watched. In a universe in which time flows backwards, our ability to act, to make decisions and choose the path of our own lives becomes impossible. Once he has made his tragic mistake – invoking the curse – he is reduced to the role of observer, trapped behind his own eyes, as his life unspools like that metaphorical movie unrolling in reverse.

If this poem was indeed a movie it might be like Memento, a murder-mystery told backwards from the perspective of a man who can’t remember what just happened. Just like in that movie, readers of this poem are shown little clues – those snapshots of the man’s life – and the bigger picture only gradually forms. Let’s go back to the riverside scene. Was the drowning accidental, or was this a premeditated suicide? The only clue we have is the simile came up like a cork. You can do a bit of forensic investigation yourself: find an old cork and hold it underwater in the sink. Then let go. See how it shoots to the surface? Think about this motion in reverse: you may conclude that the man could have leaped purposefully into the river, plunging precipitously to his death, before invoking his salvation/curse. The violence with which he resurfaces is suggested through hard, guttural alliteration: came up like a cork.

As we leaf back through the scrapbook of the man’s past, we begin to piece together more clues about the life he led up to this moment. This guy suffered. And not just any suffering, but the enormous agonies of passion. Needless to say, this language is hyperbolic, three strong words in a row combining to assure us his feelings were too much to contain. Each word also features assonance, an expansive O sound that echoes the depth of feeling felt by the man. We see him try to channel this emotion into writing poems. There’s a brilliant line where he writes his poems from the end backward, an image through which the writer now erases his own words. Tantalisingly, we’ll never know what answers were written in these lines as they disappear before our eyes. What is clear is that the writing process failed to purge the man of his pent-up emotions: him brushing away tears that had not yet fallen suggests he was never able to cope with his pain.

It’s not until the next stanza that we meet the intended recipient of his poetry and the meaning of his tears becomes clear. He was in love with a girl, watched her from afar and, presumably, never told her of his feelings. Why? We don’t know for sure but possibilities glimmer under the surface of stanzas three and four. The way he watched her swinging in the garden may suggest his love was not appropriate. Was there an age gap or another socially unacceptable reason he could not approach her? Perhaps not; perhaps she was simply a neighbour and it was the innocent shyness of his own youth that prevented him from reaching out to her. The unique non-chronological structure of the poem allows us to understand that, whatever the reason for his paralysis, he waited too long to act on his emotions. One day she was gone (words that don’t appear until stanza five but, in a reality where time moves in the right direction, would have preceded the furious writing in stanza three) and it was this that spurred the man to belated and futile action – the writing of grief-stricken poems that could never be read.

Dobson continues to employ strong diction to convey the depths of the man’s helpless emotions. In stanza four the word wildly suggests a variety of connotations. On one hand, the word links with passions, to suggest his fervent love. On the other, the word implies a lack of control (think about phrases such as ‘wild child’) and we should perhaps consider the strangeness of a watcher who never says anything to someone he has such strong emotion for. We might also wonder where – or more precisely, when – the ‘wildness’ of his emotion began. Was it in his original lifetime or a result of him reliving his cowardice over and over again? The word also suggests the way he may flail wildly, but hopelessly, against the supernatural power that traps him in this eternal time-loop.

By this time, the backwards movie reel is running faster and faster. The poem consists of isolated visual images: we get fleeting glimpses of the mysterious girl, sharing the man’s perspective in stanza four as he watched her from afar. Trapped in his curse he sees her as she grew younger; but we know, of course, that this means ‘grew older’ in reality. His inaction is conveyed through contrasts. Look closely at two verbs in this part of the poems: she is the active one (swinging) while he is passive (watched). She is described as bare-footed and clothed in straw in a way that suggests an affinity with the natural world. There is something symbolic about the garden, as if the man is forbidden from entering. He is a part of the river, that flow of water – and time – from which he cannot escape. Her ‘grounding’ in the real, Earthly world contrasts with his metaphysical existence. Is the detail of a woven straw hat a way of aligning her with the three sisters, the ‘weavers’ of fate? Perhaps, although this is a faint allusion at best. What these concrete details do achieve, though, is to give the girl a solidity and vividness that makes the way she fades away in the final stanza all the more moving and memorable. It’s a great way to recreate the impact she had on the man, whether she knew it or not.

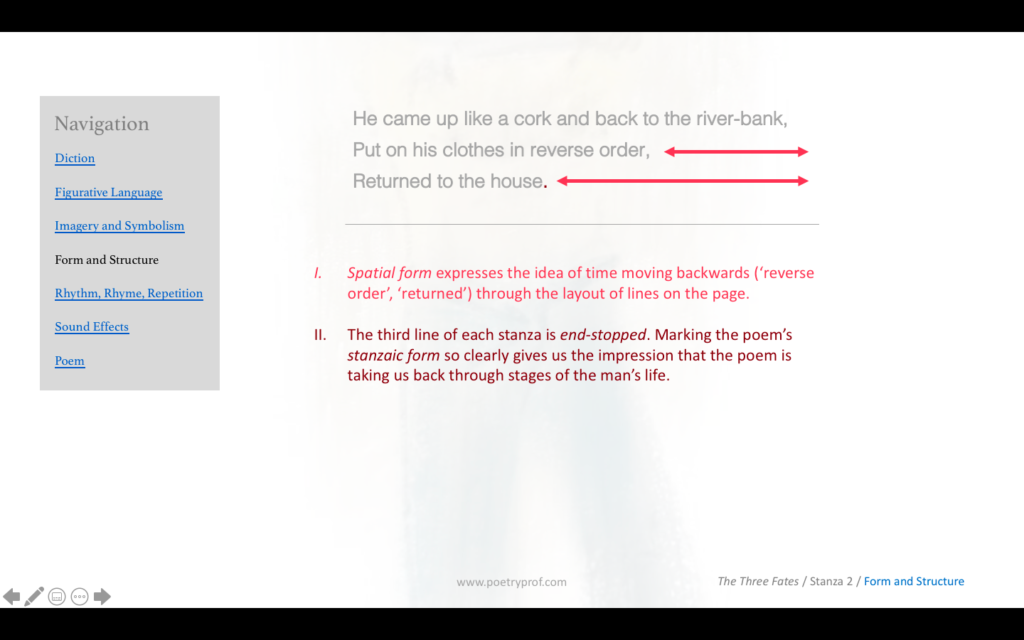

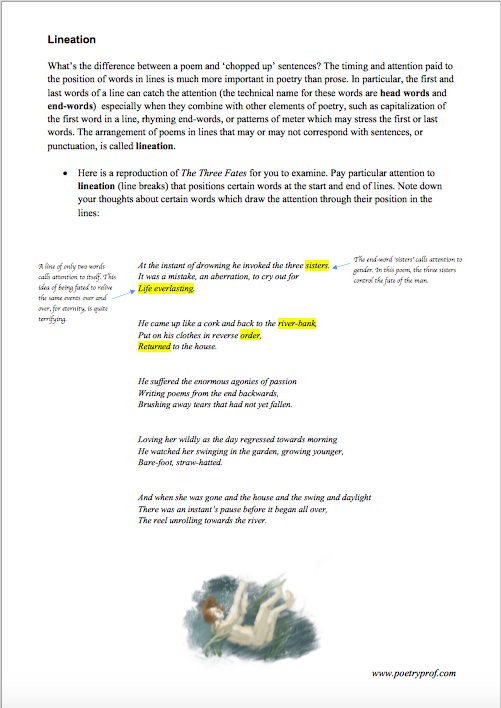

The poem’s form is carefully constructed to frame the back-to-front unfolding of the story. Most obviously you can see the idea of ‘reversal’ in the shape of the lines on the page, the three lines of each stanza contract, regressed, and seem to move ‘backwards’ into themselves. Enjambment, by which lines of poetry run on one to the next, contributes to the feeling of movement too. The first line of the final stanza is all flowing movement: the list of things that fade – she… and the house and the swing and the daylight– is joined together three-times by ‘and’, a technique called polysyndeton. ‘And’ sews the list together more smoothly than commas, helping to conjure both the sense of time flowing and the ceaseless flow of the river to which he always returns. The final line of the poem completes the transmutation of the river into time through alliteration using L, W and R: The reel unrolling towards the river. Technically called liquid, these three sounds are perfect for creating fluidity, the flow of the river and of time itself.

Throughout the poem, Dobson combines the motif of water with repeated backwards movements in order to suggest the reversed flow of time is like the flow of water in the river, carrying the man inexorably and inescapably through his life. For example, we watch from a river-bank where we see the man come unnaturally up… and back, put his clothes on in reverse and returned to the house. In stanza three we see tears that have not yet fallen. In stanza four daylight regressed and the girl grew younger. Finally, at the end of the poem, we come full circle and go back to the river where the story began all over. By the end of the poem, it becomes clear that the man is thoroughly trapped in both time and space, his life framed by and reconfigured into a sequence of repeating images that flow like the river. We only get to see one or two of these: a bare-footed girl, a straw hat, the swing, the house, the river. In itself, this sparseness of information creates the impression that the man lived a small, constricted life even before the curse fell upon him. There’s an interesting parallel between the forward-and-back movement of the swing and the man’s new reality, trapped in a narrow arc of time that he experiences over-and-over again, ceaselessly. What makes the man’s situation so pitiable is the realisation that, despite the horrific curse placed on him, he brought all this down on himself. Is his condition now – watching, unable to act – actually that different from his life the first time around, in which he watched, unable to act?

Thoughts like this, in my opinion, take us to the heart of The Three Fates which can be read as a cautionary tale against living in the past and allowing regret to define our lives. Of course, in reality time only flows in one direction, so the decisions we make in life, the actions we take – or don’t take – are irrevocable. No matter how much we may wish to have second chances, go back to do something better or fix a mistake, maybe it’s better to accept that we can’t change the past. By leaving the actors in her poem unnamed, Dobson implies that a reluctance to act and a belief in the providence of fate to decide our lives for us is a universal mistake. Realising this may inspire us to shape our own futures instead of relying on such indifferent forces – fate, luck, destiny – to lead us down the ‘correct’ path. In this way, Dobson’s poem can be placed in a tradition of literature exhorting readers to live their lives to the full; poems with this message are called carpe diem poems (from Latin meaning ‘seize the day’). After reading The Three Fates, we may be reminded to seize more of life’s opportunities the first – and only – time around.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- To His Coy Mistress by Andrew Marvell

A famous example of a carpe diem poem, Marvell’s speaker tries to persuade his mistress – using perfect logic – that she should relent to his amorous advances.

- She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways by William Wordsworth

One of his ‘Lucy poems’, Wordsworth’s speaker loved a girl who lived deep in the woods. She lived unaware that she inspired such emotion from afar, until one day it is too late…

- Dry River by Rosemary Dobson

Dobson returns to one of her favourite motifs in this poem where a dried-up river acts as a metaphor for the challenges of writing and the creative process.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Three Fates at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to explore our bespoke study bundle for this poem. Costing only £2, the bundle includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining Dobson’s use of Spatial Form and Lineation.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… Discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of The Three Fates? Do you think the man tried to kill himself? Who are the three sisters? Do you agree with our take on the idea of Fate? Why not leave a comment, start a discussion or let us know what you think below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Great analysis guys.

I’ve just come across this blog and would like to commend the work you are doing. I run cieliterature.com, which started out in much the same way.

I hope you are able to sustain the free and open model for analysis. I just found that over time it becomes increasingly difficult to justify the time spent writing and creating content. If you ever fancy joining the dark side (subscription based analysis) please get in touch and I’d be delighted to see if we can work something out.

Keep up the good work!

Mr Sir

Hi Sir,

Thank you for your compliment.

I agree, it does take quite some time to write good content and create all the images and resources. For now, though, our aims are quite modest and we are focusing on poetry. If we wanted to cover all the other elements of literature it would be difficult (impossible?!) to sustain.

Best of luck with your project. Perhaps we will cross paths in the future :o)