When Stevie Smith gets knocked down, she gets back up again.

“She knew how the repetition of words and phrases could create music and cast spells…”

Caitlin Kimball, poet and writer.

Stevie Smith used to be thought of as a ‘minor’ poet. Because she favoured short lines, simple language and playful rhyme schemes, her poems were read as easy poems for a rainy day. She doodled beside her drafts as she wrote, simple shapes of people and animals that appear childlike. Perhaps her style of poetry and mode of address derived from her day job; she was employed for thirty years as secretary in a moderate publishing company working on banal magazines. But, to dismiss Smith’s poems as twee and naïve would be a big mistake. Like more famous poets such as William Blake and Rudyard Kipling, she used the lightness and simplicity of her language to disguise her wrestling with ‘big’ themes: love, death, God, misery, protest, the role of religion in society, the ways we treat each other, and more. Taking as its theme the emotion of melancholy, today’s poem is no exception. Often used as a straightforward synonym for ‘sadness’, melancholy can also be thought of as an emotional ailment, the condition of feeling persistently gloomy and depressed, an oppressive mood that is impossible to shake off. Yet, mired in deep melancholy, people can find inspiration too. Smith’s poem explores the idea that melancholy is a motivating force, that in trying to combat sadness we bring meaning to our lives. Ultimately, she believes that goodness and love can co-exist alongside tragedy in our unhappy world – and that melancholy is partly why:

Away, melancholy, Away with it, let it go. Are not the trees green, The earth as green? Does not the wind blow, Fire leap and the river flow? Away melancholy. The ant is busy He carrieth his meat, All things hurry To be eaten or eat. Away, melancholy. Man, too, hurries, Eats, couples, buries, He is an animal also With a hey ho melancholy, Away with it, let it go. Man of all creatures Is superlative (Away melancholy) He of all creatures alone Raiseth a stone (Away melancholy) Into the stone, the god Pours what he knows of good Calling, good, God. Away, melancholy, let it go. Speak not to me of tears, Tyranny, pox, wars, Saying, Can God, Stone of man’s thought, be good? Say rather it is enough That the stuffed Stone of man’s good, growing, By man’s called God, Away, melancholy, let it go. Man aspires To good, To love Sighs; Beaten, corrupted, dying In his own blood lying Yet heaves up an eye above Cries, Love, love. It is his virtue needs explaining, Not his failing. Away, melancholy, Away with it, let it go.

The poem begins with the speaker wishing her depression would just go away and leave her alone: Away, melancholy, away with it, let it go. This line is repeated so many times through the poem it becomes a chorus or refrain. There are tiny variations within the repetitions that I’m sure the eagle-eyed amongst you have already noticed. For example, the second verse ends with a straightforward: Away melancholy while the third verse ends with the same words separated by a comma: Away, melancholy. This tiny caesura (a deliberate break in a line of poetry) creates the effect of a little choke or closing of the throat as melancholy threatens to overwhelm, or connotes the tug of effort as she tries to push her misery away. The final line of the fourth verse, building on the repetition, reads: Away with it, let it go. While these tiny variations don’t alter the underlying meaning of the lines – the speaker repeatedly wishes for relief from melancholy – they do imply she’s not entirely sure how to rid herself of her negative feelings, as if she’s trying something different each time but those gloomy clouds just refuse to lift. Both away melancholy and let it go are expressed as imperatives, and repetition at the beginning of lines of poetry (Away… Away… Away…) is called anaphora, two techniques combining to emphasise her deep desire to divest herself of a feeling that’s weighing her down. While the action of ‘letting something go’ might seem simple, as if the speaker can just open her hand and sadness will naturally fall through her fingers, it apparently isn’t that easy. After all, she repeats her wish ten or so times throughout the poem, and even ends with exactly the same two lines as she began. This loop composition, where the end of the poem returns to the beginning, implies that melancholy is impossible to wish away or easily ‘let go’.

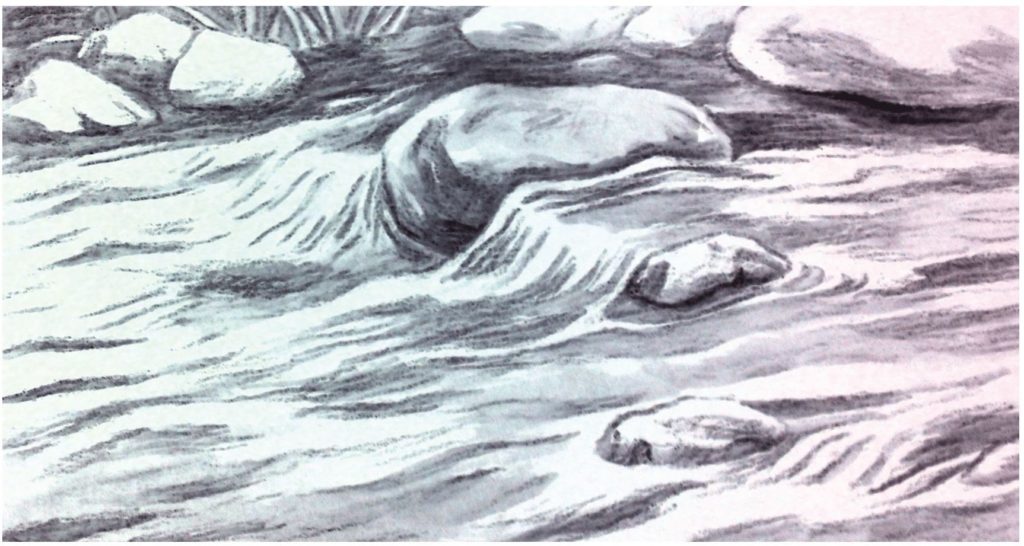

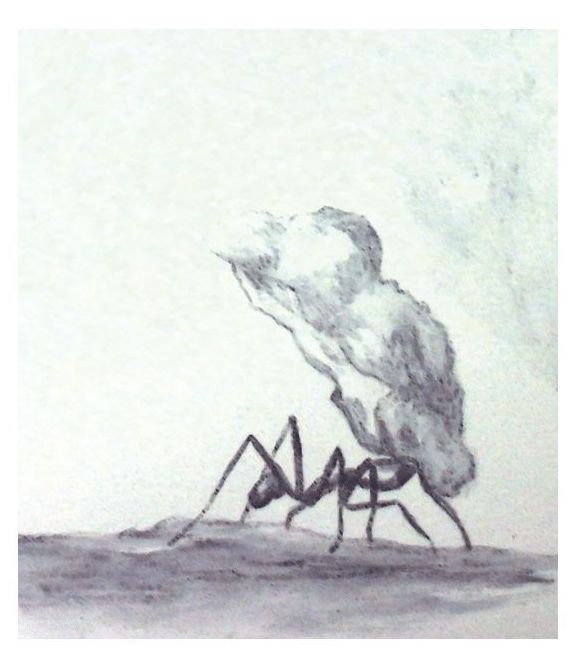

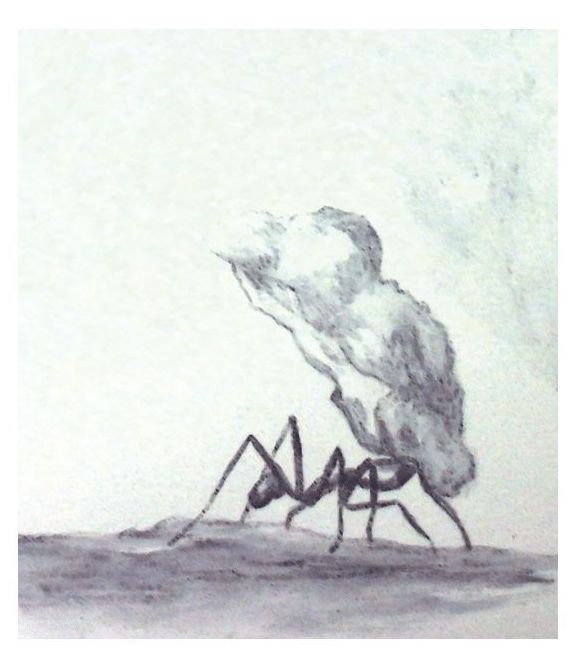

As her melancholy refuses to lessen, Smith wonders whether it’s just ‘in our natures’ to feel sadness, as it’s in the trees’ nature to be green, in the river’s nature to flow, in the ant’s nature to eat and so on. Her use of rhetorical questions in verse two implies the answer is self-evidently ‘yes’. The sense of movement in each of these images also suggests that our melancholy has no impact on the natural world, fire leaps and ants scurry around regardless of our emotions. If this is a kind of reverse-psychology supposed to make her feel better, it doesn’t work very well – it simply seems as if her sadness is holding her back from truly immersing herself in such a rich and verdant world. Therefore, as sadness seems to be an inescapable part of the human experience, Smith makes it an ineluctable part of her poem too. No one could argue that Away, Melancholy is anything but a sad poem; the feeling experienced by the reader as he or she reads is a poem’s mood or atmosphere. While there are many ways to evoke a certain mood (choice of word, imagery, repetition and so on), Smith uses the most direct method: sound. Sound is so effective because it bypasses many of our brain’s processing systems and goes straight to our emotions. It doesn’t rely on you knowing the meaning of words or visualising images. Even the youngest babies respond to sounds before they know any words. That’s why filmmakers pay so much attention to the soundtrack of a movie; sound tells the audience, in a direct way that’s hard to resist, how to feel. Tugging at your heartstrings as you read, then, you should be able to recognise assonance, which is the repetition of vowel sounds. Thanks to the poem’s refrain, Away melancholy, the letter A is an obvious example of assonance. But it’s far from the most important. Long O sounds do more than anything to evoke sad feelings; O is deep and rich, resounding mournfully in the ear. The repeated word melancholy bears a lot of responsibility again, but you’ll notice how Smith brings the rhyme scheme of her poem into play: go, blow, flow, also cause each line to tail off sadly because of an extended vowel ending. Other vowel sounds such as long EE/EA in trees, green, leap, busy, hurry, eaten, eat and the like thicken the brew, dousing the whole poem in a feeling of ineffable sadness. Smith reminds us that assonance is created through similarity in sound, not repeated letters; the same long E sounds are created with EE, EA, Y and even IE (buries, for example). All my examples are taken from the first four verses – if you want practice identifying assonance for yourself, try to locate the same combination of vowels (long A, O, and E) creating the same sad mood in the second half of the poem.

By implying so strongly that sadness is an inevitable part of the human condition, Smith suggests there’s a certain level of paradox in trying to rid oneself of sad feelings. If a river didn’t flow, it wouldn’t be a river anymore; if the wind didn’t blow, it wouldn’t be wind. Logically, therefore, if a person doesn’t feel, would we still be human? This idea is made explicit when Smith asserts that Man of all creatures is superlative; she means that we only surpass other animals (superlative means ‘of the highest quality’) because of our capacity to feel. While an ant might have a short, tough life (to be eaten or eat) – you won’t hear an ant complaining about it. In every other way, Smith argues, we are just like the animals: Man… eats, couples, buries, he is an animal also, the tricolon (pattern of three) of actions reducing the totality of life to the most basic elements shared by humans and ants both: eating food to live, reproducing, and eventually dying. The similarity between human and animal is also reaffirmed grammatically; Smith uses archaic language forms when she describes ants scavenging for food: the ant… carrieth his meat (‘eth’ is a Biblical suffix, or word-ending, now fallen into disuse. In the Bible, the word meat refers to food in general). She uses the same archaic suffix when she describes man… raiseth a stone, as if humans and ants are not so different, rather they are extreme variations of creatures both. In their basic, fundamental actions, all living creatures from ants upwards – including people like you and me – are animals. Take away our capacity to feel deeply, even if those feelings are burdensome, and we might be able to get through life more comfortably – but what would be left except animal instincts and behaviours? The simplification of language in the poem works wonders when this question is considered. For example, when writing Man, too, hurries, eats, couples, buries, Smith completely fractures her lines using commas to create caesura. The effect of this list-like writing is curiously wooden; by stripping language down to its most basic and elementary parts she implies the idea that ‘surviving’ like animals and ‘living’ like people are two completely different things – and emotions, even negative ones, are essential for the latter.

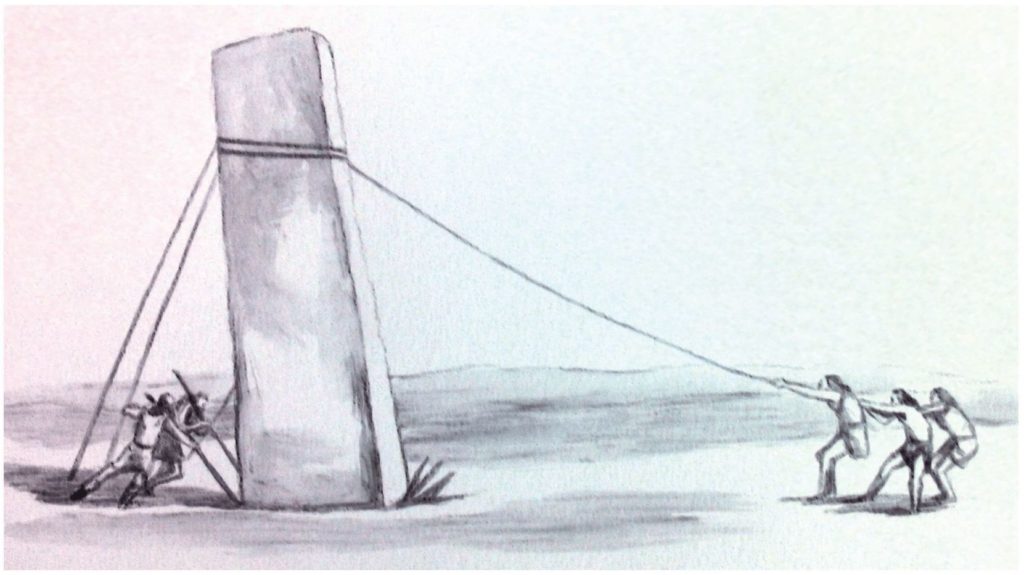

That’s not to say we can easily dismiss the suffering of persistent melancholy. Anybody who’s felt the bereavement of loss or fought depression can attest to the traumatic power of sadness. Yet Smith suggests that it is because we are dragged down so low that we aim so high. In the fifth verse, she shows how man of all creatures alone raiseth a stone – we are the only ‘animals’ to pursue activities that are not related directly to survival, but to the assuaging of our emotional needs and to pursue growth as individuals and as a species. To build in stone, Smith argues, to raise icons and monuments, carve effigies and statues, is to act in a way that other animals do not. In an extended sequence covering verses five to nine, Smith remembers how ancient people erected simple stone monuments (think Britain’s Stonehenge, for example, Gobekli Tepe in Turkey, or France’s Carnac Stones), just as people closer to her own time built elaborate churches and beautiful cathedrals. Smith proposes that the raising of stone is a direct response to life’s inherent and persistent tragedies. She lists tyranny, pox, wars, as forces that are too massive to overcome; the use of another tricolon creates an overwhelming effect, one tragedy following another, so that if one disaster is survived the next is just around the corner. As the raising of stone is a symbolic act of resistance, so the stone itself becomes a symbol of hope: we take these empty stone vessels and pour all our hopes and desires inside until the stone is stuffed with promise. She interlaces verse five with the refrain (Away, melancholy) presented in brackets like a prayer chanted by dedicated workmen raising their stone structures to ward off existential despair. The poem implies that, while misery cannot be banished, it can be channelled in a way that gives meaning to our lives. There may be an autobiographical element to this line of reasoning. Smith wrote in a diary: ‘The human creature is alone… Poetry is a strong way out.’ Herself an eccentric and loner, she knew something of depression’s power, so her poem stands as her own stone bulwark against life’s overwhelming sadnesses. Writing in verses of unequal length and in purposely short, truncated lines, the shape of her poem (also called spatial form) mimics on the page the shape of rough stone circles raised by ancient peoples in all kinds of cultures and societies throughout history.

Growing up in an Anglican household, Smith was nevertheless ambivalent about religion. She borrowed the meters and rhythms of church hymns (this poem has a hymnal quality in its use of assonance and repetition, Away melancholy sounding like an incantation or protective prayer) yet was more of a doubter than true believer. Her treatment of God differs from poem to poem; in Away, Melancholy she proposes the interesting idea that, born out of worshiping stone idols as a response to melancholy, God is a human creation rather than the other way around. In a small-but-important detail god (uncapitalised) is transformed into God through the pouring of hope into the raised stone. She questions whether, in a world where flowing rivers and green trees co-exist with war and disease (pox), pain and disaster, God is a force for good, asking: Can God, stone of man’s thought, be good? Yet she immediately dismisses the question as unimportant: say rather it is enough… and Speak not to me of tears. God, like melancholy, tears, tyranny, pox and wars, is neither good nor bad; these things exist regardless of our moral perspectives or emotional distress. It is what we do and how we act in the face of persistent tragedy that makes all the difference.

Therefore, God is described through metaphor as the stone of man’s thought, a hard place of resistance somewhere deep inside us that refuses to give in to persistent melancholy, but instead aspires for more. It is ‘hope’ that is good, rather than God him-or herself, per se. Smith frequently plays on the similarities between the words God and good; because they sound so similar the words seem interchangeable (for example, god pours what he knows of good Calling, good, God). Through this wordplay, the poet implies that it doesn’t matter what label you give to the power within the stone symbols and whether you even believe in God or not. What matters is that the willingness to resist rather than succumb is fostered in the hearts of humanity. A corollary effect of all the wordplay is a plentiful smattering of hard, guttural sounds that underpin the middle section of the poem. Made by the letters G, C and K, gutturals ring in the ear like hammers chiselling stone, and audibly ‘push back’ against the poem’s dominant assonance. Guttural sounds are strongest in the lines: god pours what he knows of good calling, good, God… Can God be good? and Stone of man’s good, growing, by man’s called God. Out of all this jumble, the word growing stands out. Combined with aspires from verse eight, growing depicts mankind strengthening under adversity, not giving up, raising stone edifices in a world that keeps knocking them down. Like the famous saying (or Chumbawamba song, if you prefer) goes: ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’

The ultimate ‘good’ of which humanity is capable is revealed at the end of the poem to be love. In verse eight Smith states, Man aspires to good, to love, ending this short verse with an onomatopoeia, sighs, as if love brings relief from both suffering and the effort of resistance. This verse is the briefest in the whole poem, and contains only positive diction (aspires, good, love) making it feel like a moment of respite, the calm before the storm. In such a tragic world, these moments don’t last for long; Smith uses a semi-colon that forms a caesura between verses eight and nine, holding us amid gentle sighs… before plunging us into misery and desperation with a renewed ferocity. Gone is the green and pleasant land of the first couple of verses. At the start of verse nine, she creates the most distressing image of the poem in which a personification of the whole of humanity is beaten, corrupted, dying in his own blood lying. It’s a potent image of despair, mankind completely vulnerable against cosmic forces that are simply too powerful to defy, heightened by another tricolon so each word strikes like a hammer-blow driving humanity to its knees. Against tyranny, pox, war, and melancholy, moments of aspiration, contentment, and love are quickly snuffed out.

Only… the flames of resistance flicker but won’t completely die. Beaten to exhaustion and near death, yet driven on by a relentless desire to fight despair, man finds the strength from somewhere to oppose fate one last time: yet heaves up an eye above, cries, Love, love. Smith describes this final superlative effort using the phrasal verb heaves up, expressing both exhausted defiance and affirming the ‘upwards’ direction (raiseth a stone) of human aspiration: growing, aspires, heaves up, above. With his last breath, the dying man chooses not to complain any more about his miserable life, or to wish away his sadness, but to express Love in place of the poem’s refrain (verses seven and eight are the only ones not to end with a variation on Away, melancholy…). Smith marvels that, despite all the cruelty and unfairness of the world, humanity still has the capacity for emotions such as love, prayer, faith, and idealism. At this high point of the poem, Smith employs rhyme again: three rhyming couplets in a row (dying/lying, above/love, and explaining/failing) create ‘poetry’ that illuminates the idea of virtue – mankind’s ability to proclaim love for his fellow man even when everything and everyone is failing, to hold onto light even in the darkest moments.

Smith prefers to imagine that some good can come out of bad experiences and emotional suffering. Afflicted by persistent melancholy that refuses to abate, she channels her misery into meaningful action. To take away melancholy, you would have to take away the capacity to feel deeply; without the full range of human emotion there would be no good, cooperation or love in the world. These are the things that separate mankind from animals and make us into ‘superlative creatures’; you won’t hear an ant complaining about feeling sad – but you won’t hear him proclaiming his love for his fellow ants either.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Deeply Morbid by Stevie Smith

In this wonderful poem an office girl escapes the mundanity of office life and heads off to the pictures and museums all alone. One day, while staring into a Turner seascape, the colours seem to reach out and envelop her, drawing her into the painting. When she doesn’t turn up for work the next day, people wonder what became of her. A beautiful example of Smith’s poetry at its very best.

- Ode on Melancholy by John Keats

Like Smith, Keats believed that sadness is an inevitable part of the human condition. He reasons that in a world of conflict and oppositions, sadness is inextricably tied to happiness – one is the inverted twin of the other. So he warns his readers not to try to escape melancholy feelings; rather, wallow in misery and try to find some kind of joy hidden inside sad experiences.

- Lucky Life by Gerald Stern

This fantastic poem has so much in common with Smith’s outlook on melancholy. Stern contemplates life and all its misfortunes, remembering moments of joy mixed with sadness along the way. He stops to describe two statues of Christopher Columbus, one hunched and pained, the other proudly guiding the way. Just like Smith, he sees symbolism etched into the stone surfaces of our statues and edifices.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Away, Melancholy at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining Smith’s uses of repetition in the poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Stevie Smith’s poem? Do you agree with this interpretation of the raising of stone in the poem? Do you think the poem asserts or rebukes the existence of God? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

this poem is sad but cool

I think Stevie Smith would very much appreciate your comment :O)

love this in-depth analysis !! keep it up