Tony Harrison’s father copes with grief in his own way.

“People know what he is talking about…”

Simon Armitage, fellow poet, on Tony Harrison’s appeal.

Poet, playwright, critic, scriptwriter, lecturer, novelist, journalist, translator. If it can be written, Tony Harrison has written it. His topics and themes are as broad as his mastery of the written word; he’s covered war, politics, religion, class, race, history, places he’s lived (including Leeds, Nigeria, Prague and Sarajevo) and more. But, in today’s poem Harrison focuses his gaze on a much narrower subject – himself. Formally titled Long Distance II and written in 1981, the piece below is the continuation of a poem (Long Distance I) he wrote in 1978 about the death of his father. The title nods to Harrison’s relationship with his parents which he spoke about in an interview; he was worried that life’s path would take him away from his family. He even admitted, ‘My mother hated my early poems.’ It wasn’t until after his father and mother died that he found a way to address them in his writing: Long Distance and Long Distance II are part of that process, exploring themes such as whether knowing someone and understanding someone is the same thing. As the poem begins, Harrison recalls his father’s odd behaviour following the death of his mother. He seems confused that his father insisted on acting as if his mother was still alive and presents his actions as an unhealthy form of denial, something he neither approves of nor fully understands. His response is to try to push his own father through the five stages of grief, getting to ‘acceptance’ as fast as possible. But his father doesn’t process grief in such a logical, linear way. For him, denial isn’t a stage on the way to acceptance – it is his way of accepting his wife’s absence. While we may be inclined to assume that denial isn’t a healthy strategy to take, Harrison’s poem might prompt us to reconsider this viewpoint and ask whether, in some instances, denial might be an effective or necessary response to grief. Only by pretending that his wife is still alive can his father cope with such an impossible loss:

Though my mother was already two years dead Dad kept her slippers warming by the gas, put hot water bottles her side of the bed and still went to renew her transport pass. You couldn’t just drop in. You had to phone. He’d put you off an hour to give him time to clear away her things and look alone as though his still raw love was such a crime. He couldn’t risk my blight of disbelief though sure that very soon he’d hear her key scrape in the rusted lock and end his grief. He knew she’d just popped out to get the tea. I believe life ends with death, and that is all. You haven’t both gone shopping; just the same, in my new black leather phone book there’s your name and the disconnected number I still call.

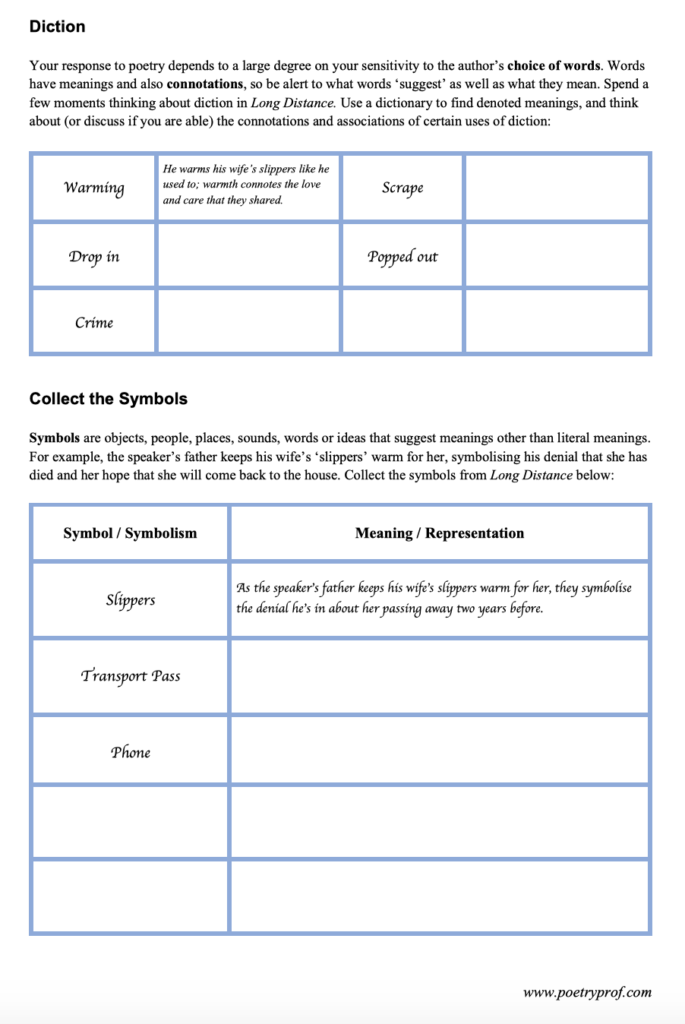

The first stanza focuses exclusively on the actions of Harrison’s father as he struggles to cope with the death of his wife, the poet’s mother. His father’s small, pitiable gestures are symbolic of his grief, a debilitating emotion that prevents him from accepting the reality of his wife’s absence. Through the son’s eyes, we see the father ritually following the habits of life when they were still two together: warming her slippers next to a gas fire; heating her side of the bed at night; going to renew her transport pass (in Britain, people over the age of 60 are entitled to free public transport, they just need a pass to show to the bus driver). Each of these actions is small, tender, and meaningful, painting the picture of Harrison’s father as a caring man, protective of his wife in a traditional way that is quite endearing. However, listed in this way, one after the other, the accumulation of small actions also reveals how grief can lead to denial; it’s so hard to accept the passing of a loved one that the father prefers to live in an illusion, pretending his dead wife will return from a shopping trip at any moment, and things can go back to the way they used to be before her death. His attempts to keep her memory alive trap him in the past; he seems stuck there as other people move on, implied by the rusted lock in stanza three.

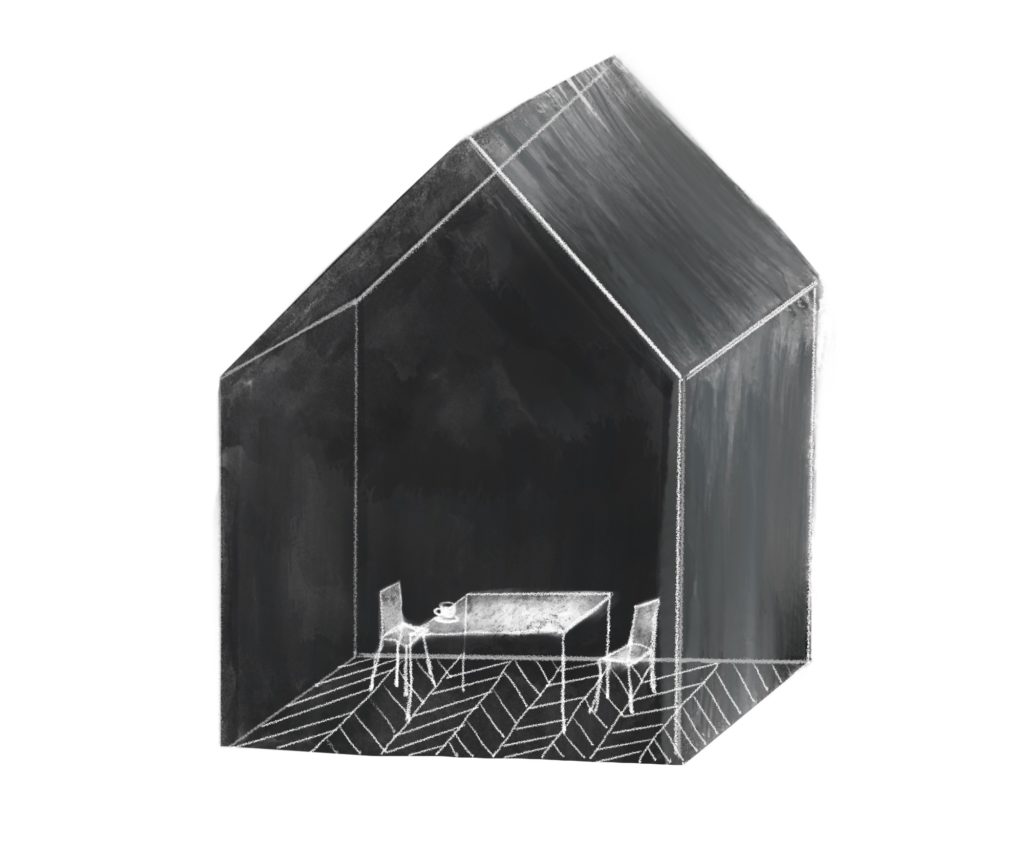

The lock is just one of many small, everyday items that become loaded with difficult emotions after the death of the father’s wife. The key is another, this tiny object symbolic of his stubborn refusal to give up the hope that his wife might unexpectedly return with the tea. The phone is a symbol too, connecting with the title of the poem through the idea of a long distance phone call. Instead of symbolising communication between father and son, it comes to represent the awkward distance that has grown up between them as we see their relationship newly mediated through this object. The phrase you had to phone transforms a spontaneous chat into a formal act, made difficult by the little word had, and abruptly curtailed by caesura (the full stops in the middle and at the end of the line) as if the call is brief and fraught. Even the items that the father so carefully arranges in the home become loaded with significance: through the understated symbolic association of love with ‘warm’ objects (gas fires, snugly warm slippers, hot water bottles) the poet suggests the comfort of a long, intimate relationship and evokes images of a warm, loving home. Yet it’s through such a vivid impression of warmth that we can so easily imagine the ‘coldness’ of life lived suddenly alone. References to so many objects reminds us of the conscious act of will that brings his father’s illusion to life, as if they are all props in a stage play. He could ‘exit’ the performance at any time – the phone and door key imply there are still ways back to the ‘real’ world where people process grief and move on – but he chooses to ignore them, as if reality is intrusive and unwelcome. The rusted lock again does a lot of heavy lifting, implying the front door is rarely used because the father prefers to dwell in the fantasy of his wife still being with him in the house.

This state of affairs is not palatable to the speaker of the poem, who represents the poet himself, and conflicts with his father’s persistent denial of reality. He struggles to empathise. After all, it’s been two years since his mother’s passing and he’s impatient with his father continuing to pretend otherwise. By contrast, Harrison has a pragmatic, realistic attitude to his mother’s death; look how he just states at the beginning of the poem that my mother’s already two years dead. There’s no softening of the expression, no denial, he just comes right out with it. He believes that his father’s stubborn refusal to accept this truth is neither subconscious nor a natural part of the grieving process; he thinks his father is purposely sustaining this irrational behaviour. Indeed, when he visits his father and senses his awkwardness as he acts out a more acceptable way of grieving, the poem presents this as a kind of ‘play-within-a-play’. He delays his son’s arrival so he has time to clear away her things and look alone, putting on a forced stoicism for his son’s benefit that is just as untrue as the fantasy of his wife coming home. When they are both trapped in these weird situations, Harrison can sense his father’s inner shame, as if he knows he has been caught out. He uses a simile to suggest that any display of raw love – a.k.a. grief – is like a crime in a world where fathers are expected to be stoic and bear difficult emotions ‘manfully’ rather than hide out in escapist denials.

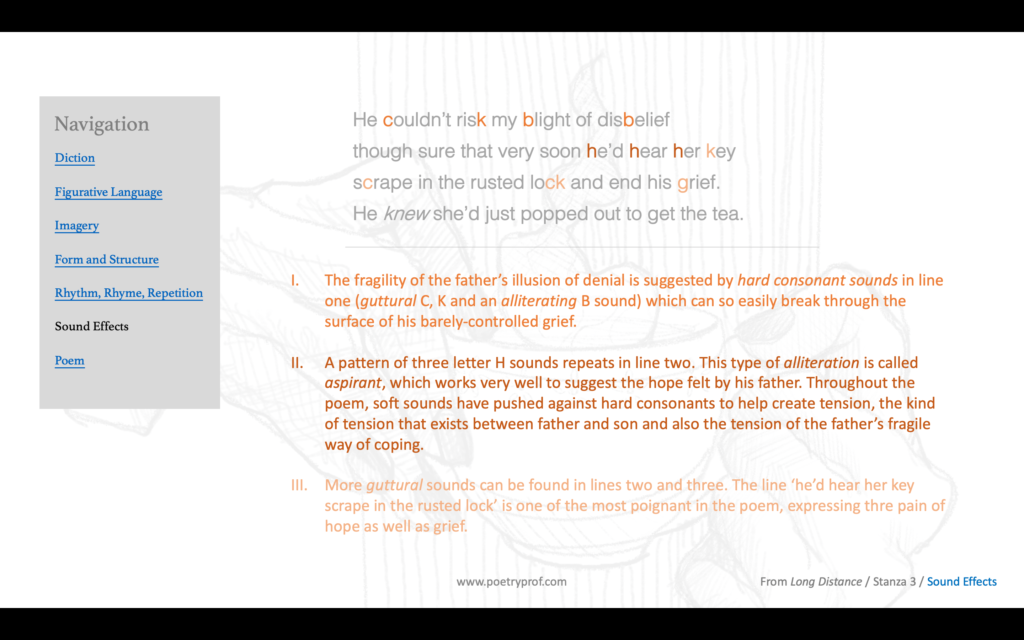

Actually, bubbling away beneath the surface, is the barely-concealed pain that the father’s performance struggles to hide. It’s audible more than anything else: Harrison’s poetry has a painful, sharp edge to it, created in no small part by a mixture of hard consonant sounds that poke like little needles of pain and grief. Right at the end of the first line the word dead alliterates with the word Dad, giving us four hard letter Ds in a row. Made by pushing your tongue against the back of your top teeth, dental D can be quite heavy and obtrusive. Similarly, bottles alliterates with bed using hard, plosive B and plosive strikes again in transport pass, blight of disbelief, and black book in stanza four. You might ask why Harrison chose the word gas instead of, say, ‘fire’ – well, gas begins with a hard consonant G rather than a softer, warmer F. The letter G, alongside hard C and K, comprises a category of alliteration called guttural, a very effective way of conveying negative emotions and experiences, such as physical and emotional pain. Throughout the poem, hard gutturals keep the father’s pain at a simmering boil, his grief roiling beneath a barely-composed façade: kept, gas, couldn’t, clear, look, crime, risk, black book again, disconnected and call. At one extremely poignant moment, a sudden concentration of gutturals reveals the keen pain of hope as well as despair: he’d hear her key scrape in the rusted lock and end his grief. On the other hand, the poem lulls us into the father’s illusion using softer patterns of sound. Verse one, for example, is ‘warmed’ by the letters W, M and N (my mother, warmed, water, went to renew) and the aforementioned he’d hear her key… begins with a pattern of aspirant H alliterations. Throughout the poem, the tension between hard and soft sounds recreates the tension between father and son and, more, implies that the illusion of denial is comforting but fragile – it needs only a misplaced word or angry reaction on the son’s part to shatter it into pieces.

Because he intrudes into and jeopardises his father’s coping strategy, the son’s visits place an increasing strain on their relationship. Harrison evokes the formality of interactions between them, and the long distance that has arisen between father and son, through elements of form. It’s no accident that the poem is written in four stanzas of four lines each (a stanza of four lines is called a quatrain). What’s more, most of the lines are ten syllables long and unfold in a loose iambic pentameter which is one of the most formal patterns of English poetry (in fact, the poem is an obscure form of sonnet called a Meredithian sonnet, named after George Meredith who first composed in this form in 1862, stretched to sixteen lines and presented in four stanzas, complete with turn at the end, which we’ll get to soon). I say ‘loose’, though, as on more than one occasion the rhythm doesn’t easily scan into iambs. Scansion is the process of discovering a poem’s meter and, by the end of line one, the unwieldy rhythm already prefaces the uneasy feeling between the two men, as if they just can’t settle into any kind of comfortable balance. Take a closer look and you’ll see that lines one and three are eleven syllables long, not ten; as it’s impossible to force an odd number of syllables into the regular ‘de-dum, de-dum’ pattern of iambic pentameter, these lines feel a little halting and broken. This is deliberate on the writer’s part, a subtle way of reinforcing how buried grief can throw one completely off-kilter, and evoking the fresh awkwardness between father and son as they fail to reconcile their reactions to the death of a person who was important to them both. The poem’s rhyme scheme works in tandem with these effects: the first three stanzas rhyme in the pattern ABAB. Also called alternating rhyme, arranged like this rhyming words are always separated from each other, a great way of implying a distance between two people who are, in many other ways, very close.

The gap that has arisen between the father and son seems nowhere wider than in stanza three, which develops the clashing of Harrison’s pragmatic acceptance with his father’s denial. Opposing coping strategies are revealed through contrasting diction, most notably the words disbelief and sure in lines one and two. The speaker’s father prefers to entertain the notion that his wife has just popped out to get the tea from a nearby shop. He has persuaded himself (is sure) that she will return from a short shopping trip; the phrasal verb popped out is casual and reflects the father’s mindset; if she just ‘popped out’ then she can ‘pop back in’ at any moment. The way a person can knowingly lie to himself, convincing his own mind of an untruth, is further conveyed through typography on the word knew in line four; the poet uses italics to imply that the father’s self-deception is so thorough that this unreal situation has become his reality. The son, wishing his father would drop the act, reacts with disbelief, described using an emphatic metaphor as a blight of disbelief. While blight can simply mean ‘to damage’ something, the word carries connotations of sickness (‘blight’ is commonly used to describe a fungal infection in plants). Therefore, the use of this word implies that his son’s attitude is fatally damaging to the father’s way of coping and is the primary cause of tension in their relationship. The first line of stanza four confirms this impression when the son straightforwardly admits: I believe life ends with death, that is all. The way this line is abruptly end-stopped with a full stop, even though it’s the first line in the verse, supports the son’s idea of dying being final. When you’re gone, you’re gone. Full stop. There’s nothing else to say.

Except… Harrison goes on to admit that he has got more to say. In a masterful final stanza (well, final three lines anyway) that turns the poem on its head, it is revealed that Harrison has, belatedly, come to understand and adopt the same coping mechanisms as his father. When he places his father into the shopping fantasy (you haven’t both gone shopping) our hearts sink as we suddenly realise his father’s gone too. So now he repeats the same performance, the same pretence that his father’s still there, even down to the imbuing of everyday objects with symbolic importance; for the father it was slippers and transport pass – for the son it’s a new black leather phone book in which he’s faithfully transcribed his father’s old phone number, even though it’s long since been disconnected. The emotion associated with this object is revealed through an extended description that gives it the weight, texture (leather) and even colour of grief (black), as well as another of those rhythmic disruptions that signal the difficulty of coping with emotional pain. The third line of the final verse is eleven syllables long, and the first foot is an anapaest, three quick syllables creating a panicked flutter as he handles the phone book that symbolises connection and understanding with his departed Dad. There’s another subtle switch at the end of the poem too: where he’s been using third person (Dad, he, his) he suddenly addresses his father directly using the word you – as if he’s finally found a way to communicate with him properly, without inhibition and awkwardness.

As the truism goes, ‘hindsight is twenty-twenty’. While the final verse of the poem redeems the speaker for his earlier impatience, metaphorically closing the long distance between him and his father, this all happens just a little too late. Tragically, it’s not until Harrison’s as alone as his father was that he comes to recognise the power of denial – it’s not always a stage on the road to acceptance, sometimes it turns out to be the end of the road. As he finds himself replaying his father’s experience, Harrison shifts the rhyme scheme from ABAB to ABBA, a pattern that expresses the way understanding brings them closer (BB) while simultaneously admitting that his father’s death makes true reconciliation impossible now (A… A). At the end of the poem Harrison reveals, in the most poignant irony, that I still call the number that will never be picked up again. Phone calls that were fraught and tense because he couldn’t empathise with his father’s way of dealing with his emotions are now the only – imaginary – link between father and son, a shared ritual of denial acted out as a coping mechanism for loss.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Long Distance I by Tony Harrison

If you want to read the full story, here’s Long Distance I, the first of two poems Harrison wrote after the death of his father. You can see some of the same symbols at play in this poem, in particular the difficult phone calls representing the distance between two people who should have been so close.

- Epitaph on my Own Friend by Robert Burns

Poetry is a wonderful way to eulogise, to remember a person after they have died. In this short and sweet eulogy from the eighteenth century, Scotland’s most famous poet remembers ‘an honest man’ at his funeral.

- A Child to his Sick Grandfather by Joanne Baillie

In another eighteen century poem from Scotland, Baillie writes from the perspective of a child who speaks to and comforts his grandfather as he dies. Initially he won’t accept the inevitability of his death, and would rather live out the fantasy of denial by imagining his grandfather’s health rallying. By the end of the poem, however, the child has come to terms with reality.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Long Distance at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining symbolism in this poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Tony Harrison’s poem? Do you agree that denial might be a necessary way of coping with difficult emotions? Do you find yourself sympathising with the father, or son, or both? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.