Is Philip Larkin dreading or welcoming the arrival of spring?

“Poetry from which even people who distrust poetry can take comfort and delight”

X.J. Kennedy (Writer and Poet)

Sooner or later, every serious student of English-language poetry will want to tackle Philip Larkin. One of the most famous English poets, Larkin achieved this status with a surprisingly slim oeuvre: The North Ship (1945), The Less Deceived (1955), The Whitsun Weddings (1964) and High Windows (1974) are the sum of his four volumes of published poetry. He was provincial and taciturn by nature, eschewing foreign travel and noted positions (he worked as librarian at the University of Hull for 30 years and refused to consider any appointment to become Poet Laureate) and, as his biographical entry at Poetry Foundation says, preferred ‘to avoid the limelight’. His poetic style was often traditional (think regular rhythms, rhyme schemes and stanzaic form) although his subject matter was almost always derived from the experiences of modern life. According to one of his several biographers, Bruce Martin, Larkin believed ‘that his own life, with its often-casual discoveries, could become poems.’ Reading through his many reviewers, you will come across a common refrain suggesting that he found many of the experiences of modern life ‘profoundly disturbing’ (Alan Brownjohn), ‘dismal’ (X.J. Kennedy) and that his poems hint at the ‘endless nothing that overlooks and underlies experience’ (J.D. McClatchy). You might agree you can feel this unsettling terror lurking just below the surface of today’s poem. Entitled simply Coming and published in his 1955 collection The Less Deceived, the poem is about the coming of spring, which should be a joyful time. But for long periods, the poem seems to keep you waiting in the time between seasons, as if you are trapped in a twilight wintery world, in suspended animation, and doubting if spring will ever arrive:

On longer evenings,

Light, chill and yellow,

Bathes the serene

Foreheads of houses.

A thrush sings,

Laurel-surrounded

In the deep bare garden,

Its fresh-peeled voice

Astonishing the brickwork.

It will be spring soon,

It will be spring soon –

And I, whose childhood

Is a forgotten boredom,

Feel like a child

Who comes on a scene

Of adult reconciling,

And can understand nothing

But the unusual laughter,

And starts to be happy.

The first stanza is incredibly economical in the way it creates a deeply unsettling atmosphere in just a few short lines. We can feel something is not quite right with Larkin’s descriptions of such an ordinary suburban scene (a long, late winter evening as the sun sets over houses and an empty garden) but are hard pressed to put a finger with any certainty on quite where the discomfort lies. Could it be the strange evening light? Described as chill and yellow, there is a contrast between the colour, which appears warming, and the feel of the light, which is cold. Spring might be coming… but it feels like winter still has a grip on the scene. The rhythm of the poetry is a little uncomfortable too. Nothing scans easily into a regular meter. One thing you might notice, though, is the number of lines that end in an unstressed syllable. Technically called falling rhythm, these weak endings hint at something unsaid, or unseen, lurking just out of sight beyond the ends of the lines. Take a look at the first four lines, with accents marked, to see what I mean:

(On) /lōnger /ēvenings,

/Līght, chīll and /yēllow,

/Bāthes the /serēne

/Fōreheads of /hōuses.

What else gives the scene that unsettling atmosphere? One feature is the spare and economical use of verbs which makes things appear unnaturally still. There’s almost no movement; there are only three verbs in the entire first stanza: bathes, sings and astonishing. The first describes the action of light. A word that is normally used to describe water, bathes suggests that light fills the garden like water in a tub. Alliteration reinforces this watery impression. Look carefully at the second line: light, chill and yellow and you’ll notice three L sounds and a W. Coming from a category of alliteration called liquid, L, W (and R) sounds helps conjure that fluid, watery sensation and lets the light flow into every nook and corner of the scene. The effect is almost hypnotic, lulling us into a false sense of security and creating a dozy, dreamlike feel.

Once the scene is filled with light, Larkin reveals what there is to see: almost nothing. As well as being too still, the garden is described as deep and bare. Peer even harder – the words fresh-peeled work together with light imagery to suggest that all the layers that might hide the garden have been ‘peeled back’ leaving it exposed to your view. There’s really nothing there except empty space. Even the birdsong seems to come from nowhere, the author of these sounds hidden by laurel leaves. (The choice of laurel links faintly to the title of the poem, as Coming could allude to the coming of Christ in the days before judgement day. Laurel leaves are symbolically associated with Christianity). Surrounding the space, these leaves also work to isolate the garden, separating it from the world outside the brickwork (that itself cuts off the garden from the outside world). There’s a sonic tension, too: softer sounds like the aforementioned liquid L and sibilant or fricative S, SH, TH (bathes, thrush sings, houses, laurel–surrounded) vie with harder sounds like plosive B and D or guttural G in, for instance, deep, bare garden. It’s possible that the thrush acts as a kind of harbinger, a messenger of warmer and brighter things to come; but at this point it’s hidden or concealed under the surface, struggling to break free in fits and bursts.

Or maybe it’s the lack of any people? A suburban garden scene should have some evidence of life – a bicycle leaning against the wall, a shoe or ball discarded in the garden. But there is no sign of anybody; even the speaker’s position is ambiguous (is he even there or is the garden scene imagined in his mind?). Instead, the houses and garden are personified. The watery light covers the serene foreheads of the houses, and the birdsong is astonishing the brickwork. There’s a dramatic difference (or contrast) between the words serene and astonished, as though the houses (and presumably their occupants) were blissfully content in their wintery solitude, and the presence of an unseen voice has shocked or startled them awake. Again, patterns of alliteration combine with the words to suggest deeper meanings: soft sounds vanish in the final line to be replaced by gutturals and plosives. Short, hard B and CK sounds fire like a gun next to the ear (see brickwork). Taking personification into account, there is something a little disturbing about the image of water covering the houses up to their foreheads. If they were people, they would be submerged, drowning. And the word serene suggests they were either content or unaware. Does the coming of spring act in a positive way, thawing out this comatose wintery scene? Or does the thrush come too late for the astonished inhabitants? The sounds at the end of the stanza had me imagining those absent people sitting bolt upright, gasping for air, suddenly realising the presence of danger.

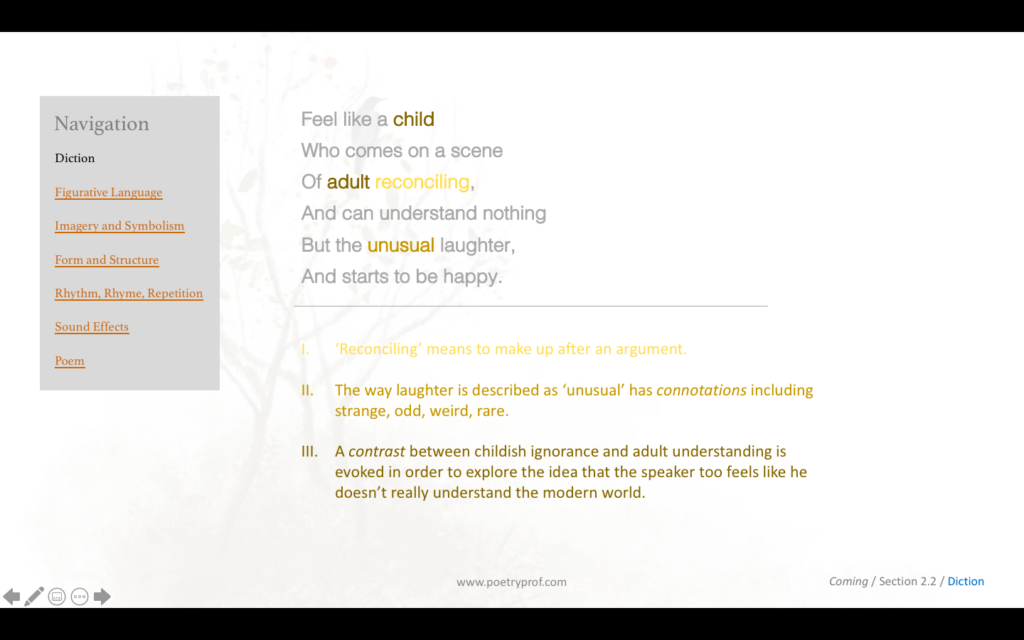

Once you’ve reached the end of the first stanza, let yourself dwell for a moment on the words you’ve just read. Given the lines are so short, every word counts. Words have meanings but also connotations. Take the word chill: on one hand it denotes the coldness of the air in late winter turning to spring. But on the other it suggests fear (think of the expression ‘a chill down one’s spine’) and foreboding. Play this game with other words in the poem: surrounding (describes the laurel trees that grow around the garden, but can also connote being trapped or captured); bare (meaning there are no plants or flowers, but connoting exposure or vulnerability) – consider a couple more (like serene, deep, peeled) for yourself. The writing is incredibly economical and a little ambiguous; the developing atmosphere of the poem is open to interpretation.

The second stanza begins with repetition: It will be spring soon/ It will be spring soon – and so much depends on that hyphen at the end of the second line. Hyphens create a variety of effects: they tend to emphasise the words that come before or after, create a dramatic or pregnant pause, or even signal an interruption. The hyphen imbues the idea of spring coming soon with dramatic tension – is it time to awaken and welcome the arrival of spring, or are the unseen inhabitants of those houses still trapped in their wintery twilight? The assonant OO in soon, thanks to repetition, weighs heavy at the end of the lines. It’s an ominous sound, filled with foreboding, and quite at odds with the quick, light I sounds in the rest of the lines (It will be spring). Again, the way you feel about the poem might be intensely personal; both positive and negative feelings seem to co-exist in the poem at the same time.

The third line turns the poem around. Where the speaker’s gaze looked outwards to describe the light, the garden and the weather, now it turns inwards and focuses on I, the speaker himself. Remember Larkin is a traditional poet and there is a long poetic tradition called the turn, or volta, by which a poem changes direction, develops a new idea, changes tone or switches perspective. Often a turn is marked by a line break or a connective (‘still,’ ‘yet,’ ‘but,’ ‘alas’ and the like): here it is signalled with that dramatic hyphen combined with the conjunction and.

After the admission that his childhood is a forgotten boredom (reminding us of the cliché that childhood is supposed to be the happiest time of life, full of vim and vigour and energetic enthusiasm. Not here) the speaker presents a simile (marked with the word like), by which he compares his adult experience to the feeling of being a child stumbling into a room in the aftermath of an argument between adults (Larkin’s parents, perhaps). The key word is reconciling, which means to make up after a fight. If you’ve ever been in this situation you’ll know what he means: smiles on lips but no twinkle in the eyes; oddly stiff body language; words that are over-polite; tension thick in the air. On one hand, this might be the moment you’ve been waiting for. You may feel that the arrival of the child breaks the frozen spell that gripped the winter scene. There are obvious symbolic parallels between children and spring: youth, innocence, and playful happiness to name but three.

On the other hand, you may picture the scene differently. Too young to decode the awkwardness between adults in this situation (And can understand nothing) all the child hears is unusual laughter and his natural reaction is to be happy. Play the connotation game with the word unusual – you might think: occasional; rare; odd; strange; disconcerting, forced. Read the lines aloud to hear the same auditory patterns being employed in this stanza as in the last, the occasional plosives and gutturals crackling through the often-quiet sounds of the poem, hinting at fractures and distresses swimming under the surface: forgotten boredom, who comes on a scene, reconciling, but, happy. The word forgotten has a peculiar power here, suggesting the past cannot be remembered. This idea makes the imminent arrival of spring troubling, as it too will erase the past. Like Brownjohn said, Larkin’s poetry conveys the disquieting notion that modern life is ‘profoundly disturbing’ and, in this example, oppressive.

To my mind, the poem concludes with the impression that any happiness the speaker feels in adult life is inauthentic, based on a lie. This idea links the two halves of the poem: the first stanza’s image of being unknowingly, contentedly submerged is reflected in the second stanza’s image of a child being ignorantly happy, unaware of the fault lines that run just beneath the surface of a fragile reconciliation, the unhappiness that can so easily be hidden under the façade of a happy marriage or a well-to-do life. Knowing Larkin’s own ambiguous feelings towards his parents (after all, this is the man who wrote the immortal line They f*** you up, your mum and dad and described his childhood as a forgotten boredom) might help us understand the pessimistic streak that runs through so many of his poems, and the unsettling disquietude, the ‘profoundly disturbing’ feeling, of Coming itself.

Suggested Poems for Comparison

- Sunny Prestatyn by Philip Larkin

Picking just one Philip Larkin poem to recommend is a thankless ask, but this poem lends itself well to comparison with Coming. Telling the story of the image of a girl on a poster that advertises a sunny holiday destination and what happens to that image over just a few short weeks, the reader gets the impression here too that the truth about the world is hidden under the surface.

- A Cold Spring by Elizabeth Bishop

Like Larkin, Bishop is more sombre about the coming of spring – at least to begin with. Her poem ends with the lovely metaphor of the fizz of champagne bubbles describing a flight of fireflies.

- Poem by W.H Auden

A strong stylistic influence on Larkin, Auden wrote this untitled poem in 1937. Like Larkin, in an image of children playing in the shadow of a tombstone, the poem suggests the world is made up of more than meets the eye.

- The Thrush by Edward Thomas

A character in Larkin’s Coming, the humble songbird thrush is the subject of this poem too.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Coming at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance for how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining Larkin’s choice of diction.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy today’s breakdown of Philip Larkin’s poem Coming? How did the poem make you feel when you first read it? What do you make of his depiction of modern life? If you have any thoughts about the poem why not share them with others in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Thanks this helped a lot, it saved more than 20 marks during my online classes.

Hi Ummi,

Congratulations on your great score. It can be tough learning online; I’m glad we were able to make things a little easier for you. Best of luck in your future studies.

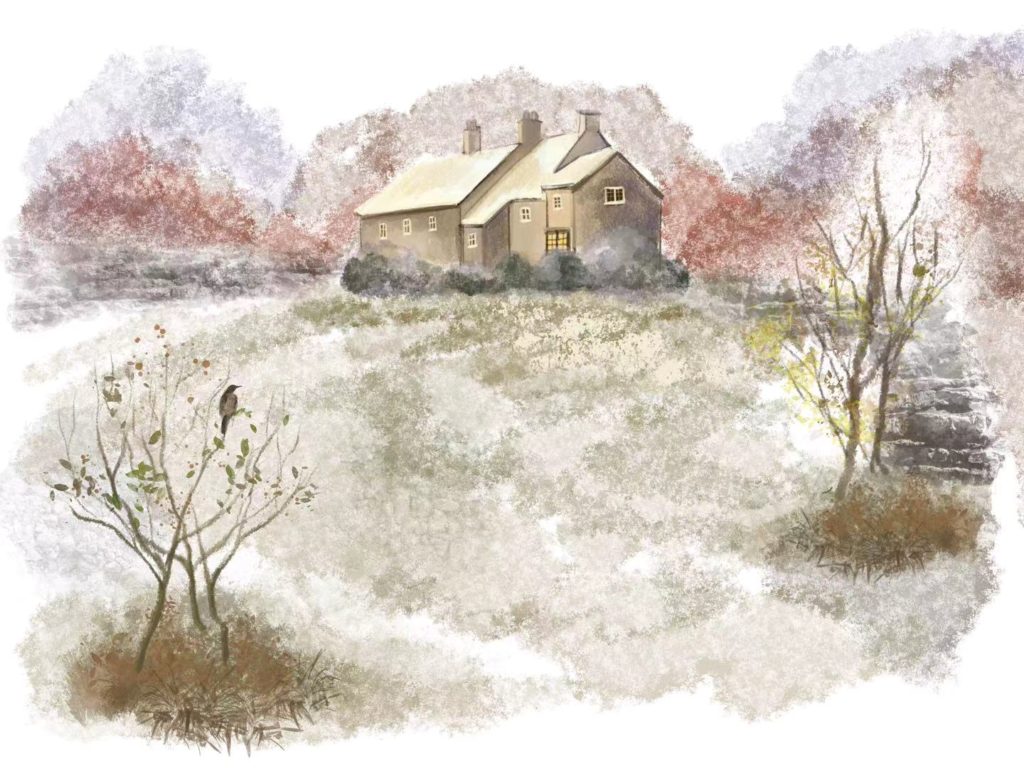

This is such a great analysis of Larkin’s poem, it was a pleasure to read! The watercolours alongside are such a lovely addition and they really capture the atmosphere of the poem!

Thank you!

Hi Liv,

Thank you for your comment. I really enjoyed working on this poem, trying to capture the suburban dread lurking under the surface of the scene. All credit to Alicia Zhou for the beautiful pictures.

This is a favourite poem. This analysis of it’s meaning does not chime with me at all. I am not an academic and not qualified to discuss the technicalities of its structure however I can understand on an emotional level and relate to what Philip Larkin is expressing here. To me this remarkable poem exquisitely describes the mysterious charge and uplift of spirit that can be felt with the onset of Spring. The bathing of light, the green of laurel, the fresh peeled birdsong, the potential of filling the bare garden – this poem is about nature bringing light, renewal, hope and and the innocent surprise and joy we can feel at this, even in the dullness of conventional suburbia. There is nothing that suggests dread for me at all.

Hi Carol,

It’s interesting how such simple language can generate such contrasting responses! I really like your phrase, ‘the potential filling of the bare garden.’ For me though, the final image of the child coming into a room after an adult conversation is what turns the poem. It makes me rethink all that came before, and I can’t help but feel a certain disquiet lurking behind the ordinary suburban scene.

One thing we can both agree on: Coming is certainly a remarkable and exquisite poem that carries that mysterious charge you speak of.

Hi Poetry Prof,

Thank you for your reply. For me the final verse is a metaphor comparing adult reconciliation to the coming of Winter into Spring, from darkness into light. I agree that one could wonder about the darkness that came before as the the laughter is described as unusual. Perhaps our individual responses are not that far apart. Some years ago this poem lead me to read more of and about Philip Larkin’s work and discovered that this was the poem that gave him the most satisfaction out of all his work.

Hi Carol,

I’ve recently come across a slim work by the sadly departed Clive James about Philip Larkin. I’m looking forward to reading it.

Hi Poetry Prof,

How kind of you to let me know about this. I recall seeing Clive James at a local theatre when he was doing a tour and talking about his own poetry. I’ll try to get a copy of this book

Thank you and best wishes.

Carol

I think the stress falls on the second syllable of serene…?

Hi James –

Yes, i think you’re right. Thanks – corrected in the blog now.