James Joyce suffers from terrible nightmares.

“This bizarre and wonderful creature who turned literature and language on end”

Richard Ellman, Joyce’s Biographer

If you’ve ever woken sweating and panting from a nightmare that seemed real, you’ll be able to empathise with the speaker in today’s poem. The ravaging, green-haired hordes from I Hear An Army… are as terrifying as any Lovecraftian monster. Charging mercilessly out of the sea, equipped with chariots, whips and flaming swords, they resemble a terrifying Roman legion on the attack; a vision twisted by Joyce into a supernatural fever-dream. Despite the visceral intensity of the poem, halfway through it becomes clear that the army are not real – they invade the speaker’s dreams, bringing fire to the gloom of sleep and causing him to shift restlessly in the waking world (I moan in sleep when I hear them from afar). The secret is revealed in the last line of the poem: the speaker has been abandoned by someone he loves and the army symbolise the crushing forces of loneliness that ‘attack’ him now that he’s all alone. Powerless to defend against their assault he becomes, metaphorically, a conquered land. The poem ends hopelessly, with the thought that the speaker’s love has gone for good:

I hear an army charging upon the land, And the thunder of horses plunging, foam about their knees; Arrogant, in black armour, behind them stand, Disdaining the reins, with fluttering whips, the charioteers. They cry unto the night their battle-name: I moan in sleep when I hear afar their whirling laughter. They cleave the gloom of dreams, a blinding flame, Clanging, clanging upon the heart as upon an anvil. They come shaking in triumph their long, green hair: They come out of the sea and run shouting by the shore My heart, have you no wisdom thus to despair? My love, my love, my love, why have you left me alone?

If you know anything about James Joyce’s famously sunny disposition, you may have been surprised at how viscerally intense and even shocking this poem was to read. Joyce was a popular child, favoured by his father, and loved to dance and sing (more on his musicality later). In any case, it’s never advised to assume the speaker of a poem and the writer are the same person. Just because Joyce wasn’t prone to depression or despair (the word dreams is tantalisingly pluralised – is this meant to be a hint?) doesn’t mean he can’t empathise with the despair of somebody who was callously or suddenly abandoned by a loved one. Or it may come from the darkest reaches of his subconscious; this is the same James Joyce who’s most famous novel, Ulysses, was banned in several countries after publication. The invasion in the dream may not be real, but it nevertheless doesn’t pull any punches for taking place in a purely imaginative realm. This isn’t a sneak attack – diction like charging, plunging, cleave, blinding, whirling, shaking and run are all-action. From the speaker’s perspective, we can hear the army’s ominous approach before we see it and, once they crash onto the beach, the noise is overwhelming: thunder, clanging, clanging and shouting summon the metal-on-metal clash of swords and shields, the deep rumble of horses’ hooves as they charge and the chaos of the battlefield – even if the site of the battle is in reality only the speaker’s heart.

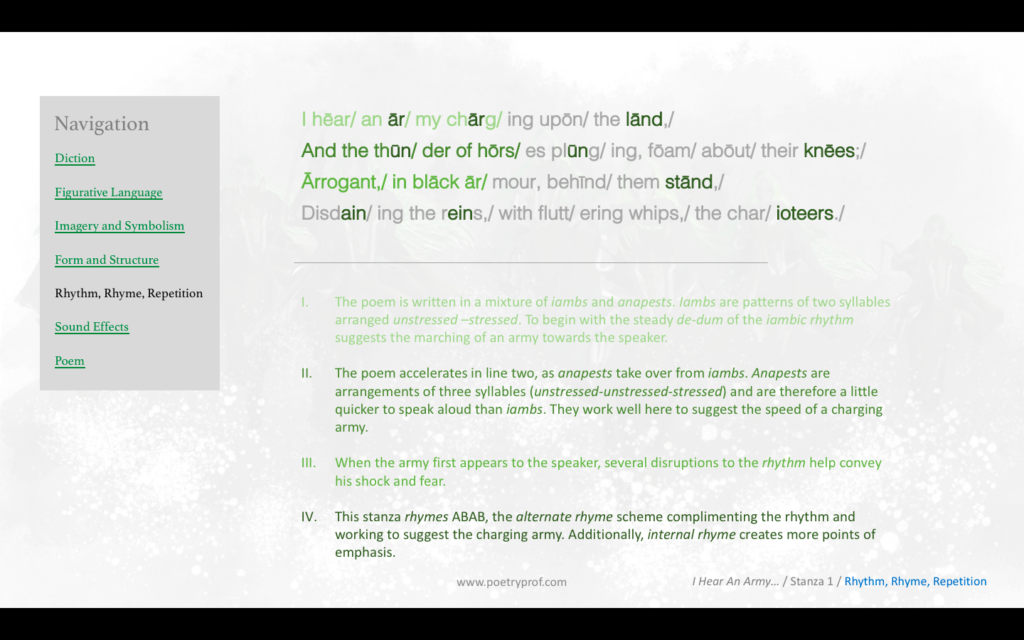

Joyce was not particularly famous as a poet, and only published two slim volumes in his lifetime. By 1932 he had given up writing poetry altogether. But this poem demonstrates the full weight of a poet’s craft as he bends different devices to a single purpose: evoking the tumult and chaos of this supernatural army’s merciless and devastating assault. Onomatopoeia is employed frequently (clanging, thunder and fluttering all contain the sounds of the words being described) and the driving rhythms of the poem (all iambs and anapaests) evoke the unstoppable impetus of charging horses and chariots. Words such as whips, moan, blinding and flame suggest that, even though it is purely imaginary, the invasion causes real pain nevertheless. The effect of psychic harm is suggested by caesura, especially in the first two stanzas; for example, Arrogant, in black armour, behind them stand. Meaning a deliberate break in the middle of a line of poetry, Joyce uses all kinds of caesuras – commas, semi-colons and colons – to ‘fracture’ his lines and stanzas in a way that evokes the ‘breaking’ of a heart or the terrible, stuttering fear suffered during such a vivid nightmare.

I Hear an Army unfolds rapidly in a kaleidoscope of garish images that slam into the back of your eye with the force of a firecracker. Like blinding flame, lots of these images are visual, as if Joyce is intent on bringing your worst nightmare visions to life. Beginning with the foam swirling about the knees of their fearsome horses to their intimidating black armour, to the blinding flame, to the long, green hair the army shakes in triumph as it charges up and down the beaches in the third stanza, the procession of images comes thick and fast like a house of horrors dream-sequence from an old movie. Long, green hair is arguably the strangest and most lurid visual image, creating the impression that army is alien, anathema to human happiness. There’s a real ‘them-and-us’ opposition in the poem, created by the repetition of the word ‘they’ at the start of so many of the lines, as if the world of simple human desires can’t stand against the coming of these supernatural beings.

Actually, this strong visual aspect is a quality of James Joyce’s body of work. While not formally an Imagist poet, Joyce is associated with Imagism through Ezra Pound and poems that share much with Imagist craft and philosophy. The Imagist movement began in 1908 when a group of poets, including Pound, formed a ‘school of images.’ Pound became the guiding force behind this ‘school’, writing a manifesto and using the French term Imagiste. He published an anthology called Des Imagistes, which contained the work of a wide range of writers and included Joyce in later anthologies of Imagist poems. Pound even singled out I Hear an Army… as a poem whose images transcend words.

There are several tenets of Imagist poetry, one or two of which are particularly relevant to us here. Firstly, the reliance upon concrete language and an aversion to abstract language. Amy Lowell, an important Imagist, wrote, ‘we are not a school of painters, but we believe poetry should render particulars exactly and not deal in vague generalities, however magnificent and sonorous.’ Imagist poets can be placed in opposition to what Lowell called ‘cosmic’ poets, as the aim of Imagism is to produce ‘poetry that is hard and clear, never blurred or indefinite.’ Therefore, despite the bulk of I Hear an Army being set explicitly in a dream world, the quality of the images in the dream are stark, clearly drawn and defined with concrete – not abstract – language. Let’s look at couple of examples:

Arrogant, in black armour, behind them stand, Disdaining the reins, with fluttering whips, the charioteers

Diction in these lines is carefully and precisely chosen to allow the reader to picture the army of loneliness exactly in their minds: they wear ‘black’ armour and brandish ‘fluttering’ whips. Consider how a poet may have described the army – wearing ‘fearsome’ armour, with ‘frightening’ whips. Black and fluttering are concrete words, positioned as close to direct sensory experience as possible – you can see the colour black, hear the flutter of barbed whips as they swish through the air. Even the word disdaining contains the visual hint of a condescending sneer with cruel, downturned lips.

One or two of the words just listed bear closer examination. Fluttering is strangely delicate diction (another poet might have chosen ‘scourging’ to describe whips, for example). Yes, onomatopoeia helps recreate the sound of ropey strands in the air as the charioteers brandish their ragged whips overhead, but so would the S sound of ‘scourge’. It contrasts with other words in the poem which are hard like metal (armour and anvil). What it does do is collocate (collocation is the pairing of complimentary verbs and nouns, as if they are good friends) nicely with the mention of the speaker’s heart in stanzas two and three, as if his heart flutters out of fear, or even in faint recognition, in concord with the vision before him. Cleave is another interesting choice of diction. It’s a polysemic word as it has more than one assigned meaning which happen to be diametrically opposite: cleave can mean both to split apart or to force together, to separate or join. Associated with the swinging action of a huge sword, in this line it means to cut, or split apart, the darkness of the speaker’s dream. In fact, this whole line aptly illustrates the confusing tumult of the poem:

They cleave the gloom of dreams, a blinding flame

You might like to consider the usual connotations of light and dark – light is often used positively, whereas dark represents negative forces. In the second stanza these associations are reversed. The speaker was mired in gloom, perhaps using sleep as an escape from reality, a respite from pain in the waking world. The ‘armies of loneliness’, though, will not let him rest. Their flaming swords are described as blinding – imagine being cocooned in darkness and suddenly opening your eyes to powerful light, and you’ll get an idea of how disorienting (don’t ignore whirling from the previous line) the effect is intended to be.

You can choose any image in the poem and find the same precise use of concrete language: the army don’t cry ‘threateningly’ or ‘fearsomely’, and the sounds of their terrible swords clanging, clanging… as upon an anvil employs onomatopoeia to render the clash of metal on metal semi-audible (again, another poet might have written, ‘like a terrible bell,’ or some such). Arrogant jumps out as a rare adjective, a describing word. It also happens to be a curiously human one, combining with disdaining to give the army ‘character’ or ‘personality.’ Are the speaker’s dreams subconsciously giving us little clues about the one who left him so alone? The quixotic visual detail of long, green hair could reflect the way dreams take real world figments (such as a woman who left me alone) then twist and distort them into something ugly and frightening.

More important than the visual, though, is the auditory power of I Hear an Army… Joyce was trained as a musician and one of his books of poetry (he published only two) was called Chamber Music. Many of his poems have such strong musical properties that they have actually been set to music. The terminology ‘imagery’ perhaps biases us to think of images as a visual component of poetry – but in fact any use of language that sits close to sensory perception (visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory or kinaesthetic) can be an image. Don’t forget the title of the poem – I Hear An Army… – letting us know in no uncertain terms Joyce’s dream army is going to make an auditory impact. We’ve already discussed some instances of onomatopoeia, and the thunder of horses, whirling laughter, moan in sleep, clanging and shouting on the shore are all fairly obvious auditory images, helping to evoke the clamour of invasion and chaos of battle.

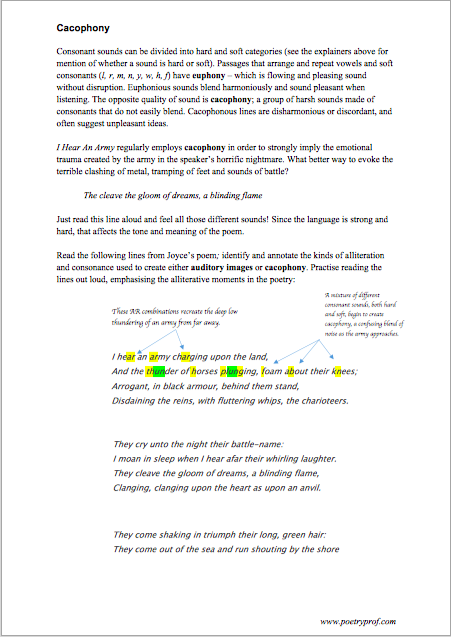

But all this pales in comparison to the patterns of alliteration and consonance (these differ in that consonance repeats sounds within a word while alliteration repeats only the sound of the first letters) Joyce employs to evoke the terrible cacophony of the charging army. At various points in the lines Joyce accentuates the force and movement of the army with alliteration (shouting by the shore is a good example) and internal rhyme. We are used to poems placing rhyming words at the end of lines (such as land / stand in the first stanza) so sometimes other types of rhyme are overlooked: check out army / charging, thunder / plunging, disdaining / reins in the first stanza alone.

If euphony is the arrangement of flowing, pleasant sounds (vowels and soft consonants) cacophony is the opposite: a group of harsh sounds that clash and clang like the spiky metal armour and weapons borne by the dreadful invaders. In this one line alone, you can count seven different consonant sounds, most of them hard and none of them harmonising:

They cleave the gloom of dreams, a blinding flame

Try this exercise for yourself with a couple of other lines (they come shaking in triumph their long, green hair works well) and you’ll begin to appreciate the sonic whirlwind – technically called cacophony – that Joyce whips up. As a supremely clever piece of juxtaposition, lines which focus on the thoughts of the sleeping speaker (such as I moan in sleep when I hear afar their whirling laughter or My heart, have you no wisdom, thus to despair) contain almost no hard consonant sounds: hear / afar / laughter and heart / have rely on softer F, aspirant H and assonance (repeated vowels) as sound effects. What better way to suggest the absolutely alien quality of the invading army, and how much psychic damage it deals to the unfortunate victim, than through utilising the opposing qualities of sound in different lines. You might also notice the first line contains mainly softer consonants and vowel sounds, as the speaker hears the rumble of the distant army drawing nearer before they crash onto the shore.

Suddenly, halfway through the final stanza, the all-action violence of the poem is replaced by something more contemplative. As if a switch has been flicked, the sights and sounds of the army disappear; the abruptness of the change creating the impression that the speaker has suddenly awoken from his terrible dream, eyes snapping open, breathing raggedly. The poem still has one or two lines left to contemplate the images lingering in his mind’s eye. The first, My heart, have you no wisdom thus to despair? is a little tricky in terms of grammar and perhaps the word thus might throw you a little. It might help to break the question down a bit: My heart, have you no wisdom? Let’s assume the answer is ‘no’, raising the interesting possibility that this isn’t the first time the speaker has been left bereft by the leaving of a loved one. Could the repetition of my love, my love, my love be more than a plaintive cry – is it a list of past disasters? I’m not sure, but you might like to consider this as a possibility. Have you no wisdom? has the angry tone of an accusation levelled at himself – that he has not learned from his experiences in the past. Thus (‘therefore’) when he is abandoned once again, his heart is open and vulnerable to despair.

Ending the poem with two rhetorical questions creates uncertainty, as if the speaker is flailing in the face of such destruction. The final question, in particular, suggests futility. If love is a fortress that protects against despair, the green-haired armies of loneliness (symbolism which is finally confirmed by the last word of the poem) have devastated his defences and left him bereft, alone in the dark.

Suggested Poems for Comparison:

- La Belle Dame sans Merci by John Keats

Is it a dream? Or is it real? When Keats wrote this poem he was dying of tuberculosis. The horrifying truth about the beautiful faery lady with the ‘wild, wild eyes’ is revealed at the end of his strange, dreamlike journey.

- Dulce Et Decorum Est by Wilfred Owen

If you like war imagery, nothing beats this brutal masterpiece. Killed at the age of 25 just before the end of the first world war, Owen was writing from the heart – and from first hand experience.

- We dream – it is good we are dreaming by Emily Dickinson

This poem makes an interesting counterpoint to Joyce’s poem as it prefers the world of dreams rather than the good and danger of the waking world.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying I Hear An Army… at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining types of alliteration, consonance and cacophony.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for revision or a recap lesson.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you find this analysis of James Joyce’s poem useful? How do you respond to the fearsome images in the poem? What do you make of the charging army’s long, green hair? Can you recommend other vivid ‘dream poems’? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. You can also find us on Social Media – if you like us, follow us there.

Fantastic resources from the one and only Poetry Prof! Keep it up, sir 🙂

Hi James,

Thank you for your kind comment – so pleased you’re finding the site useful. Best of luck!

Really helpful and insightful!

A small question, if the creatures are an anathema to the persona how would ‘my love, my love, my love’ be a calling to past disasters as after every disaster the army of loneliness would fire on the persona. Hence the persona would be used to the army and may even fight back.

Keep it up, sir 🙂 These are amazing resources which are helping me soo much with IGCSE literature.