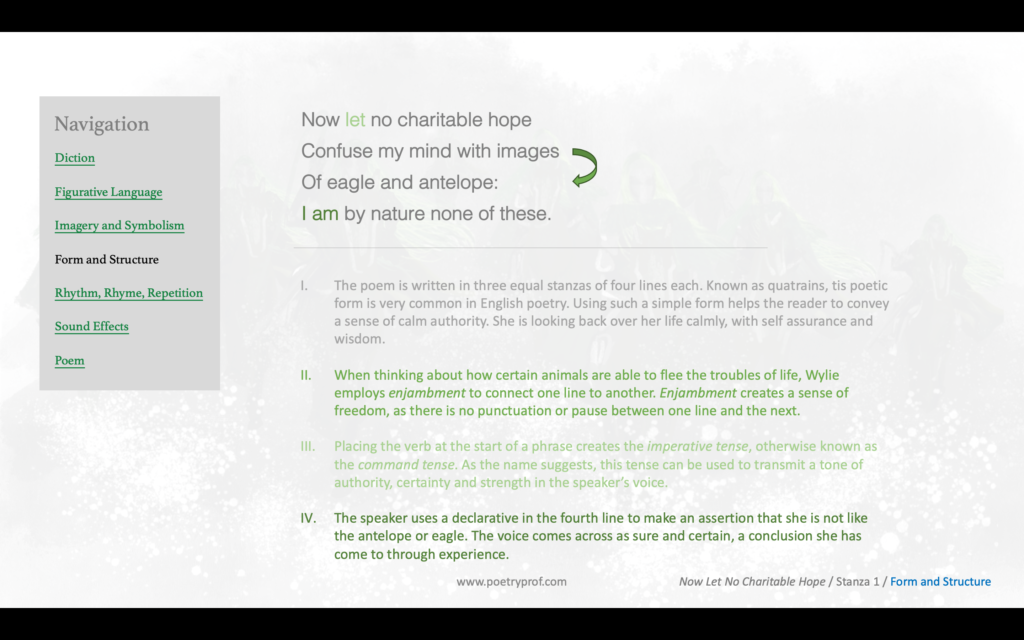

Elinor Wylie teaches us to face adversity with a dignified smile.

“[She] calls realistic attention to the disappointments of marriage and the contradictions and constrictions of traditional womanhood.”

Karen Stein, writer for the Dictionary of Literary Biography

You might think that someone like Elinor Wylie, who’s father was a solicitor in the US president’s advisory circle and who had been born into high-society, would be pretty satisfied with her lot in life. But today’s poem can be read as refuting the notion that privilege and position automatically equate to happiness:

Now let no charitable hope Confuse my mind with images Of eagle and of antelope: I am by nature none of these. I was, being human, born alone; I am, being woman, hard beset; I live by squeezing from a stone What little nourishment I get. In masks outrageous and austere The years go by in single file; But none has merited my fear, And none has quite escaped my smile.

Elinor’s parents had high expectations of her. Her father had worked his way up into a position of influence and respect, and he wanted his daughter to enjoy the trappings of his success: parties, social engagements, perhaps a convenient marriage to a hot-shot lawyer or up-and-coming doctor. Her parents may have hoped for such a match. But Elinor married a poet, of all people! This relationship, though, was not destined to end happily. Elinor scandalously eloped to London with a married lawyer, Horace Wylie, and her first husband would eventually commit suicide. The new couple would return to New York, where they could now be married. It seemed like Elinor had finally made the match her parents had hoped for.

But Elinor and Horace were to grow apart. Increasingly, Elinor moved in literary circles and began to achieve published success. Over time, this took its toll on their relationship and, eventually, they separated. Whether or not this had a saddening effect on Elinor’s outlook is open to conjecture, but she returns to the theme of life’s disappointments, including disappointing marriages, in her wider body of writing. I’m not sure how her biography might colour your appreciation of Now Let No Charitable Hope. After all, her way to a comfortable life was smoothed by her upbringing; she was handed golden opportunities which she turned down. However, having to live out other people’s dreams by proxy might feel like being put in a cage, no matter how gilded the bars appear to be. And, as hinted at in today’s poem, Elinor’s attempts to escape foundered on the realities of a woman’s position in early 20th century American society.

The desire to escape the stifling constraints of a society that ‘traps’ her is certainly apparent in the first stanza, particularly in the mention of antelope and eagle, symbolic animals associated with freedom: the antelope ranges widely over grassy plains, and the eagle, able to spread its wings and fly away, is surely a symbol of escape from earthly – or social – constraints. Words like hope, images, and mind are drawn from the lexical field of hopes and dreams which implies a contrast between her life of lived experience and an alternative, fantasy world. Unequivocally, the first line of the poem rejects the temptations of this ‘dream world.’ Let no charitable hope confuse my mind tells us that Elinor is resolute in her acceptance of her place in the world, no matter how ‘stony’ it may be at times. Her tone is one of determination, certainty and acceptance. She has learned life’s hard lessons and decided to accept and make the most of her life as it is, not feel sorry for herself that things haven’t turned out as she might have imagined. The first line is phrased in the imperative or command tense, as if Wylie is firmly instructing her readers not to feel sorry for her. Hopes for better things in life are described as charitable, something given out of sympathy or handed down out of pity. By refusing this charity, Elinor rejects the idea of changing the life that she has found herself in. The final line of stanza one is another case in point: I am by nature none of these. Her words emphatically deny that she is anything other than herself, with all the ups and downs that might bring; her emphatic tone is made even more firm and insistent by alliteration (repeated consonant sounds) particularly the N in nature none, that strongly ends the first stanza.

Actually, in common with many poems, tone is one of the most important aspects of Now Let No Charitable Hope. Tone can be challenging to infer, even for experienced readers. I’ve read commentaries on this poem that describe Elinor Wylie’s tone of voice as depressed or desperate, and I couldn’t disagree more. In times past, poems were more often composed to be heard, read aloud and even set to music, in which case, a person’s voice – inflection, volume, pace and emphasis – can help you hear the attitude of the writer towards her subject matter. To understand this point, simply imagine different ways one might say a simple phrase such as ‘pleased to meet you’ or ‘what a lovely day’. Without altering the words in any way, speak them out loud and play with your tone of voice: try sounding genuine, eager, reluctant, sarcastic or even angry. If you have a mirror, or a friend or family member who can help you with this exercise, add non-verbal signals such as gestures, facial expression, posture and body language and see how far you can stretch the tone – and therefore the meaning – of a simple phrase.

Of course, written poems don’t give you these audible and visual clues. Readers must infer only from the arrangement of words inked on white paper. Nevertheless, to misunderstand tone is to misunderstand meaning. How might you describe Elinor Wylie’s tone of voice? Is she angry, overwrought, depressed or despairing of the ill-fortune that had her born a woman in a man’s world? I don’t think so. If I was reading this poem aloud, I’d go for contemplative, certain, wise, authoritative; perhaps resigned, but not maudlin or self-pitying. The poem is written from a knowledgable, adult perspective and, while not shrinking away from ideas of hardship and unfairness, Elinor doesn’t let them beat her down either. One way of interpreting the poem is by that old adage, ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’

Therefore, even at the beginning of stanza two when Wylie develops ideas associated with hardship, she always speaks in calm declarative sentences, repeating I am assertively. If stanza one presented dreams of escape, stanza two returns us to cold, hard reality. The diction changes subtly to embrace the lexical field of hardship, felt in words like alone, beset, hard, stone and little and emphasised by the clipped and abrupt rhyme between beset and get. Wylie is not afraid to make use of plosive sounds in being, born and beset. Formed by pushing air between closed lips, plosive alliteration creates a hard sound and associates naturally with negative feelings like frustration, palpable in the first two lines of the second verse: I am, being human, born alone; I am, being woman, hard beset. Despite the negativity of the words, the sense of a speaker keeping tight rein on her emotion is conveyed through the structure of the lines. In fact, because these lines mirror each other so exactly, they form a parallelism – two phrases with an identical structure: they both contain an embedded sub-clause and are themselves balanced by a semi-colon. The effect of this carefully precise structure is to convey self-control in the face of adversity.

And what adversity. Wylie describes the processes by which she lives as squeezing (life) from a stone. In terms of hardship, it doesn’t get much clearer than this. The metaphor implies that every little win was an extraordinary effort, every moment of happiness achieved only through strain and sweat. It might be tempting to feel sorry for Wylie or think that she despairs of having to work so hard to get so little in return. Don’t forget, though, that she began her poem by refusing hope, charity or acts of kindness on her behalf. She knows she’s not an antelope or eagle. Think through the difficulty and hardship of this metaphor fully and you’ll find ideas of determination, perseverance, and success hidden on the other side. After all, to squeeze even a tiny drop of comfort or happiness (described as little nutrition) from something as hard as a stone implies enormous reserves of strength, willpower, and fortitude.

Ideas such as these are supported by an analysis of the form of the poem, the arrangement of words on the page which allows us to infer that living a tough life has made her a tough person, not easily beaten down by misfortune. The poem is presented in stanzaic form, each verse exactly four lines long (this type of stanza is called a quatrain), and composed of iambic tetrameter. This measure consists of lines of eight syllables each, ordered in a regular pattern of weak syllable-strong syllable. These weak-strong pairs are called iambs, and because there are four in each line, the rhythm is tetrameter. Here are the first two lines of the poem, replicated with strong beats highlighted so you can see for yourself. Read the lines aloud with a slight emphasis on the stressed beats to hear the regular rhythm of the poem:

Now lēt/ no chā/ ritā/ ble hōpe/ Confūse/ my mīnd/ with īm/ agēs/

Iambic tetrameter was an extremely common measure of poetry written in English before and during Elinor’s life. Perhaps by adopting the most common of measures and the most common of stanzaic forms – the quatrain – Elinor is implying her life was not exceptional, and the hardship she writes about is common to many people, a universal truth. After all, she implies that hardship is inevitable just by being woman and being human. I hear careful readers pointing out to me that in these two lines, there is a slight rhythmical variation; the first two lines of stanza two possess nine, not eight syllables. The extra syllable can be found in the word ‘being’ and this forces a little bit more weight on to the first parts of human and woman (being hū/man… being wō/man) compounding the notion that life is hard for everyone, but particularly for a woman born into early 20th century American society. And when the regular iambic tetrameter picks up again, it’s like Elinor is reasserting her control over her adverse circumstances.

Whatever life throws at her, it’s clear that Wylie has the resources to cope. She uses a figurative metaphor to imagine life (years) personified by a long string of partygoers wearing different masks, some muted or serious (austere) others funny, frivolous or flagrantly outrageous. The juxtaposition of contrasting masks suggests there’s a universality to Elinor’s life experience; whatever kind of person you are, society has a way of making you conform to its rules – look how everyone has to walk in single file. There’s definitely something disturbing about this idea, as if people who could be full of fun and life are forced into conformity, and it’s worth spending some time unpicking the layers of this image. For example: masks suggest people trying to hide who they really are, keeping secrets, nobody really getting close to one another. The image of people trudging by in a line might suggest time passing slowly, or people chained together in drudgery.

Finally, despite the alienating image we’ve just read, Elinor finishes her poem on a much more positive note, and concludes by asserting her own strength of character in the face of adversity. There’s a long poetic tradition called the turn, by which a poem shifts or changes its stance on its subject matter. Most common in sonnets, this shift can be blatant or subtle, and there’s a subtle but marked change of tone at the end of stanza three (helpfully marked with both a semicolon and the connective but). Once again, Elinor’s mastery of form comes to the fore: but none… and none… is another parallelism; the iambic rhythm and rhyme scheme that has been a feature of the poem gives her words a feeling of assurance and certainty; the juxtaposition of fear and smile helps us realise that while we may not be able to control what life throws at us, we can choose how we react in the face of hard times. Elinor has chosen to face hardship with courage and dignity. Having the last word of the poem (smile) be a positive one leaves us with the impression of the writer having gained considerable inner strength from her life experiences, no matter how difficult.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- A Crowded Trolley Car by Elinor Wylie

Society was a dangerous place for Elinor, as you can see in this poem where she rides on a packed bus watching other commuters, how they hold themselves upright, how they glare at each other.

- Lady Lazarus by Sylvia Plath

Like Wylie, Plath wrote sometimes about how disappointing life could feel. In this famous poem, a woman has to constantly reinvent herself after being let down time and time again.

- Still I Rise by Maya Angelou

A seminal poem about strength in the face of adversity, Angelou’s message applies to gender as well as race.

- Sonnet 29 by Edna St Vincent Millay

This poem shares much with Wylie’s poem, not least the insistence of the speaker that people should not pity her for her broken heart. Like Wylie, Millay considers how pain is an inevitable part of the human condition.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Now Let No Charitable Hope at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on exploring the rhythm of the poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Elinor Wylie’s poem? What is your interpretation of the speaker’s tone of voice? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

It great