Pride comes before a fall in Percy Shelley’s smashing sonnet.

“A ceaselessly energetic, desirous creator of poetry”

David Mikics, Shelley scholar.

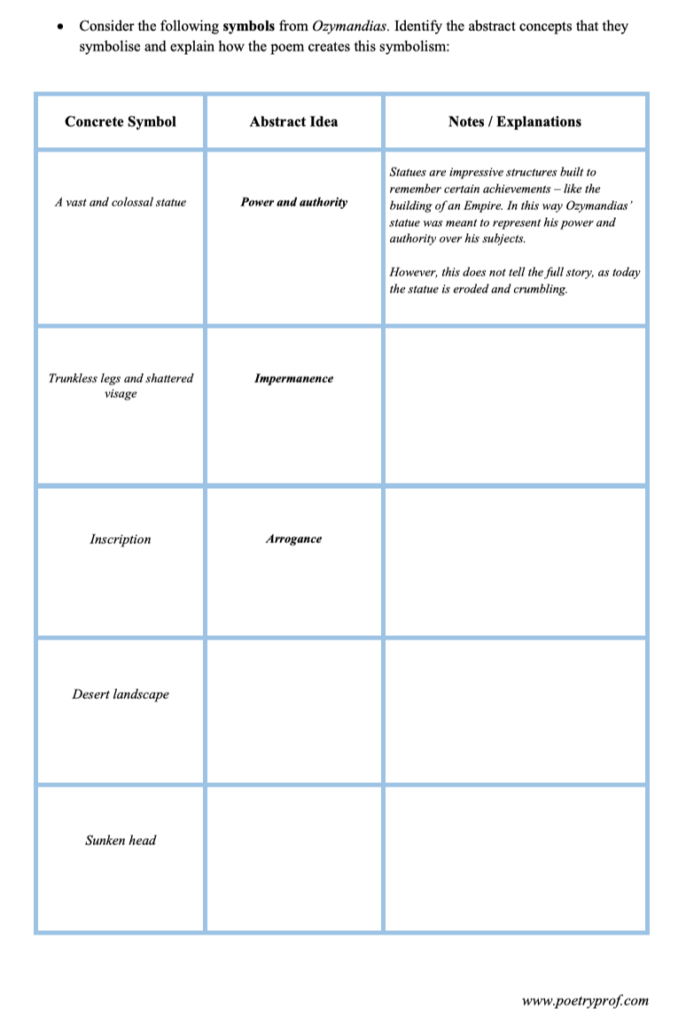

Percy Shelley had always been a rebel. He broke off relations with his father, knowing the financial hardship this guaranteed, because of a political pamphlet he wrote at Oxford university (the pamphlet got Shelley expelled). He eloped with his second wife-to-be Mary Wollstonecraft because her family disapproved of their relationship. Although he had aristocratic heritage, he wrote political and anti-monarchy poems regardless of the risks such material posed: the subject of Shelley’s 1812 pamphlet A Letter to Lord Edinburgh, Daniel Eaton, had been sentenced to prison for publishing an anti-establishment tract. In an 1813 poem, Queen Mab, Shelley deplored people blindly accepting outward shows of power and authority. In today’s poem, these lifelong concerns – aversion to authority and hatred of monarchy – marry perfectly with another of his favourite themes: the power of nature. Ozymandias was better known as Ramses II (an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled from 1279 to 1213 BC; his grand empire had long since, in Shelley’s day, fatally declined) who commissioned a statue to crown his mighty empire. Shelley could never have seen this statue as it was already long vanished, but he had read a description, including an account of an inscription inlaid in the statue’s base: ‘King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work’. In response to a challenge from one of his friends, Shelley took these meagre clues and refashioned them into his own poem which was destined to become one of the most famous sonnets ever written. Here, the great and terrible Ozymandias suffers delusions of grandeur; his statue – what’s left of it, anyway – stands only as a fractured ruin buried in the sands of a faraway desert. So far removed from any centre of power is it that the poem’s speaker only hears the story second-hand, through the words of a traveler I met… from an antique land. Rather than a monument to the powerful king of kings, the crumbled remains are testament only to the triumph of nature over the works of man, no matter how grandly conceived:

I met a traveler from an antique land Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert… Near them on the sand, Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on those lifeless things, The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed: And on the pedestal these words appear: ‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.

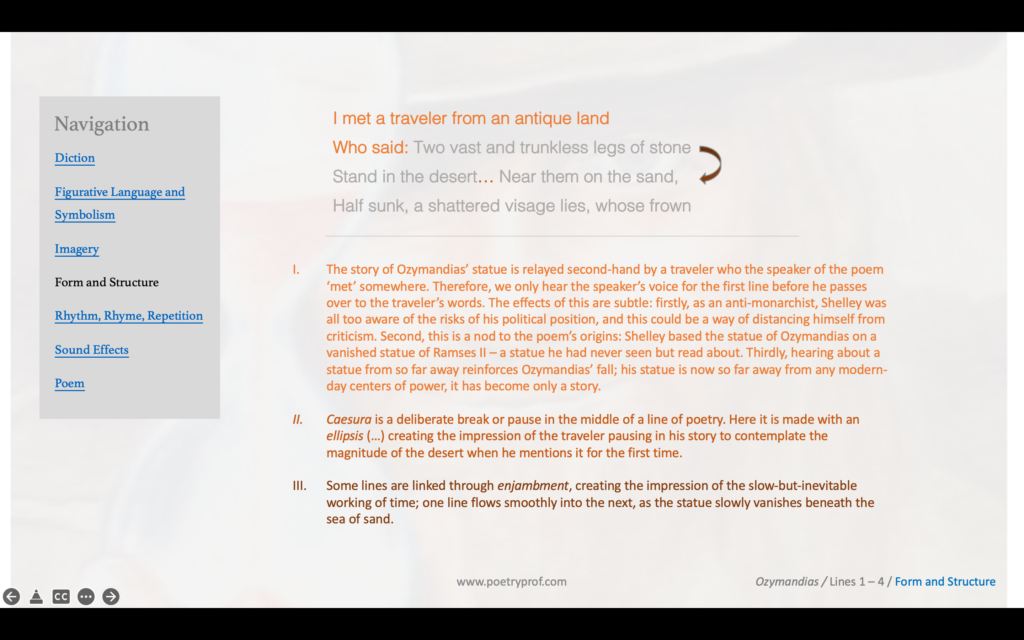

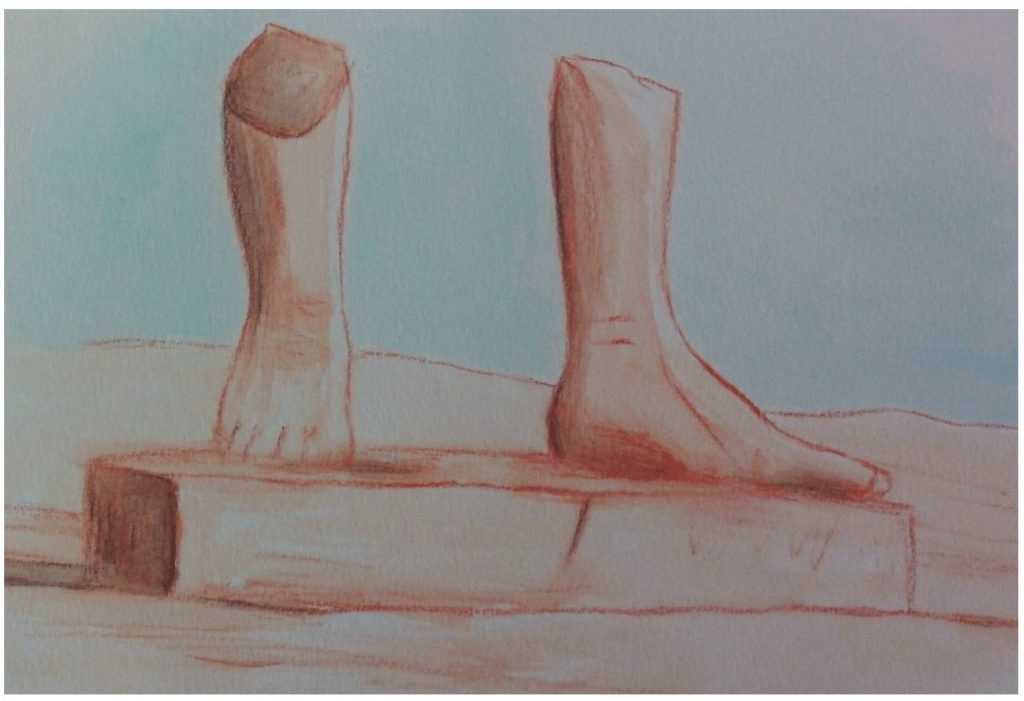

Reading Ozymandias is like being taken on an archaeological dig; each line peels back layers of sand, moving further and further back in time, and closer and closer to the truth behind the myth of Ozymandias’ greatness. The sonnet’s form helps guide us through the process of discovery: a sonnet is a poem of fourteen lines separated into two sections, an octave of eight lines followed by a sestet of six lines. In the octave, we meet Shelley’s invented speaker, who does little more than introduce a mysterious traveler whose words tell the rest of the story (Who said). He describes the ruined base of a once-imposing statue, two vast trunkless legs of stone, beside which lies the statue’s fallen head. We dig deeper still as, through traces of artistic flair stamped on the face, we feel the hand of the craftsman behind the construction and get a sense of how the supposed king of kings was, even in his own lifetime, not revered but reviled. At the end of the eighth line, the poem turns (the break between the octave and the sestet is called the turn or volta) and the focus shifts to the inscription at the statue’s base and, finally, to the desert that has consumed not only the likeness of Ozymandias, but of his former empire as well, leaving nothing but level sands to gaze upon. Shelley’s message is unmistakeable: next to the power of nature and against the true scale of geological time, the works of man are as transient and impermanent as a desert wind – here one moment, gone the next. All, even the most mighty and arrogant of kings, are ultimately subject to the forces of time, erosion, ruin, and decay.

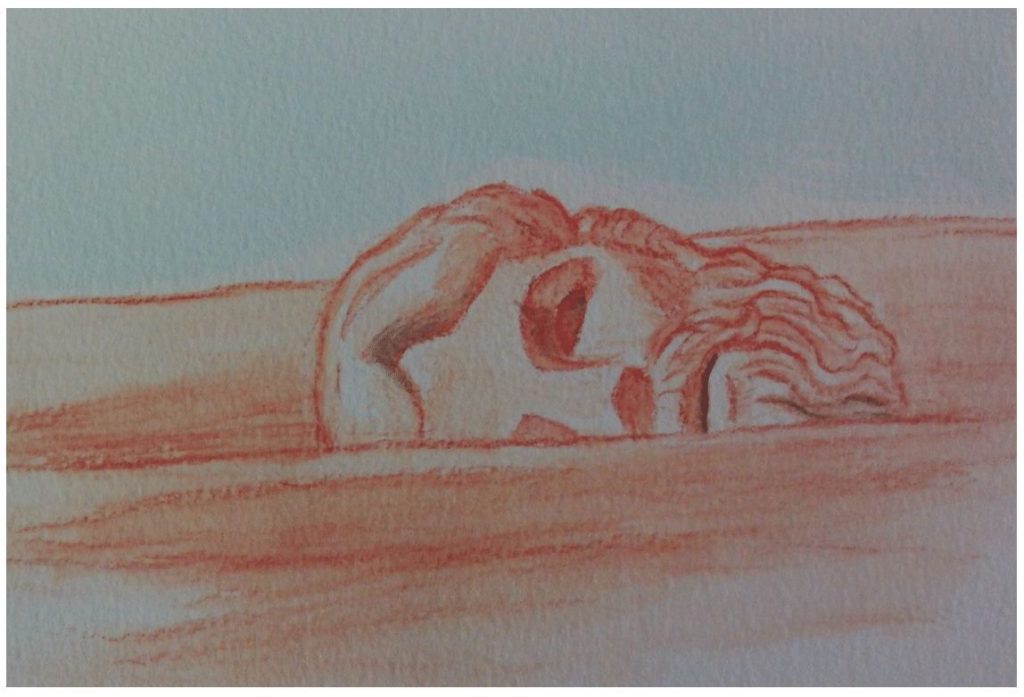

Surviving traces of Ozymandias, who he was and what kind of king he may have been, can still be perceived in the face of the ruined statue, the shattered visage, that lies half-buried in the sand. As the traveler focuses intently on the mouth, he sees carved clues that provide some insight into the personality behind the cold stone façade. The diction he uses to relay his observations is entirely hostile: frown, wrinkled lip, and cruel sneer, a sense of the ruler’s condescension evoked by the guttural alliteration of cold command. The fact that the craftsman was able to imbue the statue with these unflattering features in the first place suggests that Ozymandias was neither as well-liked nor as all-powerful as he pretended to be and the irony of the poem deepens if you consider that our impressions of Ozymandias are guided solely by the craftsman’s humble hand: a king undermined by a nameless subject. As he examines the face, the traveler’s words seem to dig deeper and deeper, penetrating through the lifeless stone exterior to the still-living presence of the artist behind the sculpture. Whoever he was, he left more to remember him than the tyrant did: contrast survive when speaking of the craftsman’s art against lifeless things referring to the pieces of the statue itself. When the traveler describes feeling the hand that mocked and heart that fed, Shelley links hand and heart using subtle alliteration. Made with the letter H, aspirant is a faint, breathy sound complimenting the almost invisible perception of the craftsman’s presence still readable in the stone. The only words of praise in the poem are reserved for this nameless craftsman, who well… read the passions of his subject. The feeling of recognition which draws the traveler closer to the artist – storyteller to craftsman – contrasts with the emotionless way he describes the cold and distant ruler and brings out Ozymandias’ arrogant aloofness even more.

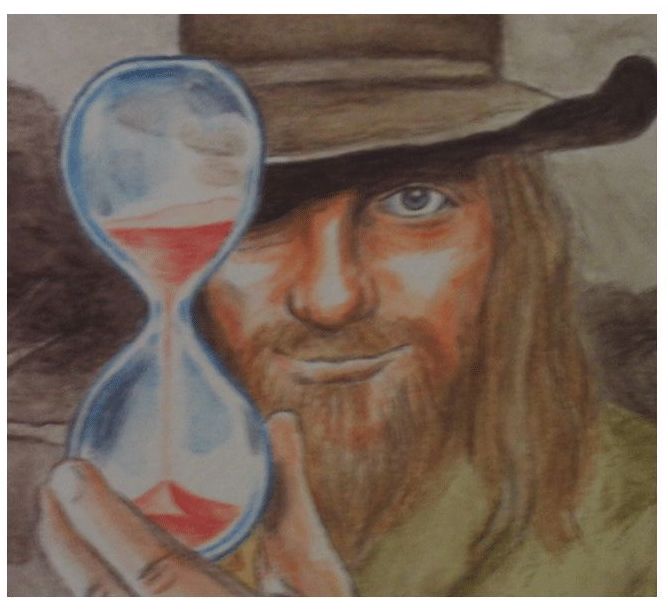

In its pomp, the statue was colossal, a word alluding to the legendary Colossus of Rhodes, a statue dedicated to the sun god Helios, and one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. It stood for fifty-four years, until an earthquake in 266BC snapped it off at the knees. Thievery, the elements, and the simple passage of time eroded the fallen remains until the statue became a memory so ephemeral that even its exact location is debated by historians today. Shelley’s poem replicates the Colossus’ demise: while vast stubs of legs remain, the rest of the statue is trunkless, meaning its torso, chest and arms have vanished into nothingness. Shelley exposes us to the power, not of great kings, but of time instead; a concept introduced in line one by the word antique and implied throughout by iambic pentameter (each line has ten syllables arranged in pairs of unaccented-accented beats): the steady ‘de-dum, de-dum’ rhythm underpins the whole poem like the implacable ticking of a remorseless clock. Time’s inevitable passing is further implied through diction. Whenever the traveler describes the statue, he uses words from the lexical field of ‘ruin’: trunkless, sunk, shattered, lifeless, decay and wreck. We tend to think of history in terms of human perspectives, where two or three thousand years of empire-building seems like a long time. But a casual glance at any National Geographic timeline reveals that, on a cosmic scale, the achievements of mere mortals, even those of kings, emperors, or pharaohs, appear as a little more than footnotes. The grandest empires the world has ever seen – such as the Egyptian empire – have all ended the same way, fallen into decay, ruin and, once enough time has passed, dust.

A-ha, I hear you cry, the statue is not completely destroyed though – the words inscribed into the pedestal have survived. Well, kind of. The words themselves have yet to be eroded into unintelligibility, although presumably one day they too will wear away to nothing. But words mean nothing without someone to read them, and Ozymandias’ grand empire has vanished without a trace. The effect of the statue’s epitaph on the traveler who’s telling the story, the speaker who opens the poem, the poet himself, and you and me, dear readers, is far from the intended effect. In Ozymandias’ day the inscription was a proclamation of triumph, an assertion (My name is Ozymandias) to strike awe and fear into the hearts of any who read them. Ozymandias was used to command and even the Mighty, including rival kings, foreign empires, and perhaps even the forces of nature themselves if that capitalization means anything, were expected to submit meekly at this display of authority. His arrogance is conveyed through imperative tense: Look on my works… Also called the command tense, the imperative is formed by placing the verb, look, at the head of the sentence. Now, though, the inscription barely inspires a rueful shake of the head. An endless desert has devoured his mighty empire, and finally the greatest of kings is himself no more than a subject to geologic forces. What works are left to look upon except the workings of time? The inscription has become ironic; all that’s left to see are the lone and level sands vanishing into the distance. Written in the present tense, the inscription’s original meaning is lost in the past. Words supposed to proclaim absolute power now suggest nothing except: ‘pride comes before a fall.’

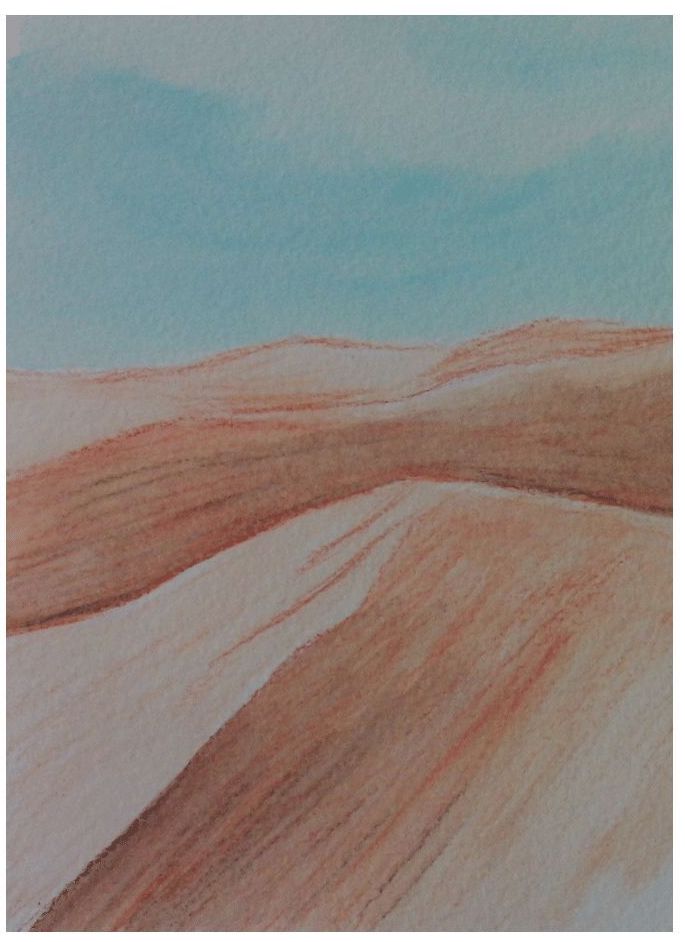

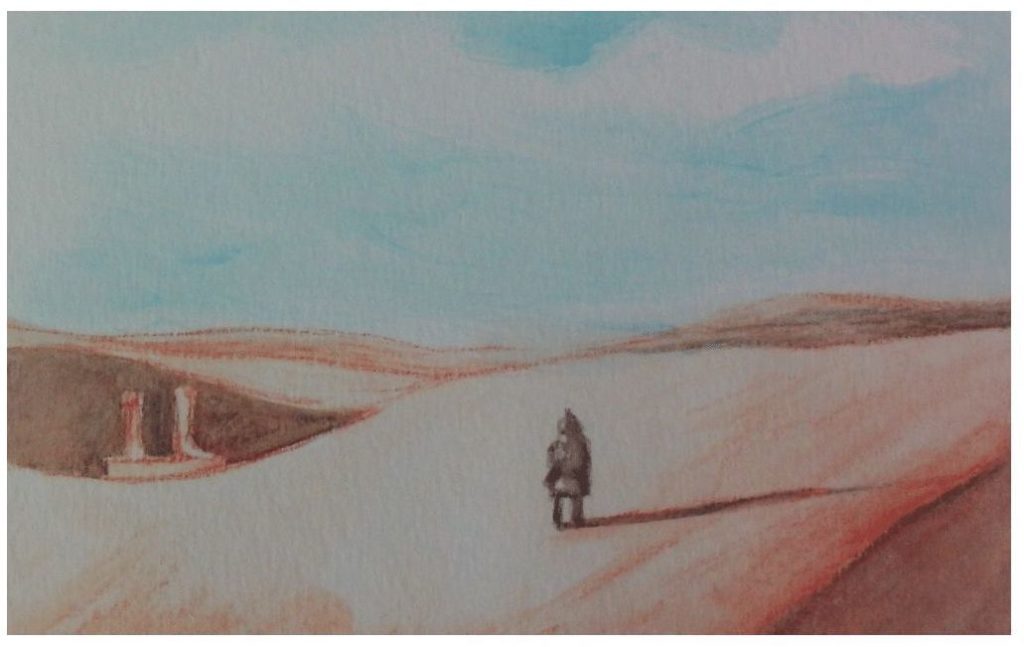

Ultimately, the poem implies the victory of nature over any of man’s works, no matter how mighty. Shelley was a proponent of the Romantic school of poetry, a central tenet of which is the idolization of nature, and the need to seek solace in nature as a refuge from the increasingly busy and un-natural human world. In Ozymandias, the power of nature is symbolised in this poem by the endless desert that stretches to the horizon, no doubt dwarfing the empire of Ozymandias even at the height of his majesty. On his first mention of the desert in line three, even the strange traveller pauses in the telling of his story as Shelley uses ellipsis (…) to create a caesura in the middle of the line. Such a deliberate gap evokes the impression that, on recalling the desert, the traveler is momentarily overwhelmed by memories of its boundless scale in which the vast statue’s legs may as well be a pair of broken chopsticks. The statue’s only other surviving piece, the fallen head, is mentioned as being half sunk, as if the desert is slowly consuming the personage of Ozymandias himself. By the end of the poem, it is as if the sand has completely devoured the ruins: Nothing beside remains. This short phrase is marked with a full stop creating another caesura as the traveler gazes around him in awe, not at Ozymandias’ works, but at the natural world instead. The landscape is so bare and featureless that it seems purposefully scoured clean; the implication that it too is ‘sculpted’ by forces of nature (wind, sand, erosion) creates a pleasing counterpoint to the raising of Ozymandias’ statue and reminds us of his arrogance. He sought to assert his dominance by building vertically, disturbing the pleasing harmony of the desert with his crass monument: natural order is restored through the emphasis of the horizontal (level) axis at the end of the poem. Shelley’s imagery evokes the desert’s austere beauty in a way that makes the statue seem vulgar, no matter how finely wrought the craftsmanship.

Spellbound, we listen as the traveler ends his story where it began, with this extended emphasis on the landscape. The poem is bracketed by the sand that’s mentioned in line three and repeated in line fourteen, forming a loop composition which helps assert the image of the desert circling around and dominating the statue. Where the statue is ‘bounded,’ the desert itself is contrastingly boundless, seeming to stretch to the horizon as far as the eye can see. Sound effects are especially noticeable at the end of the poem as pairs of clear alliterations (boundless and bare, lone and level, sands stretch) reinforce the power of nature and erase any impression Ozymandias’ statue and inscription may have made. Actually, throughout the entire poem Shelley conjures an auditory image of the desert with a faint sibilance (trunkless legs of stone stand in the desert… half sunk, a shattered visage lies… its sculptor well those passions read… which yet survive stamped on those lifeless things…) mimicking soft susurrations as countless grains of sand shift in the dry desert winds. Additionally, the last sounds of the poem enhance the great desert imagery as it vanishes over the horizon using assonance: bare… sands stretch far away.

The Egyptian pharoahs loved to build pyramids, installing themselves at the very top. As a rebel against authoritarianism and a fervent anti-monarchist, Shelley’s sonnet flips the pyramid upside down, putting Ozymandias at the bottom, beneath the forces of time, nature, the humble craftsmen who mocked him, and even the words he had inscribed, all of which have survived long after the king and his empire has crumbled into dust. Although he may have defeated his mortal enemies, in the final analysis, the mightiest and most colossal of kings has been brought low by some of the smallest forces of all: tiny grains of sand.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Time by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Another poem that conflates Shelley’s favourite themes: the passage of time and the power of nature.

- Ode on A Grecian Urn by John Keats

Shelley wasn’t the only romantic poet to explore the idea of objects revealing the impermanence of man’s creations. In Keats’ famous ode he contemplates the images engraved on the side of a simple pottery jar and sees moments from the past frozen in time.

- Kubla Khan by Samuel Coleridge

For another Romantic poem about a mighty empire-builder, look no further than this description of Kubla Khan’s (also known as Genghis Khan) palace that he built in Xanadu, a forgotten paradise-on-earth.

- Archaic Torso of Apollo by Rainer Maria Rilke

Translated from the original Czech, in this poem Rilke senses life still pulsing from an ancient statue of Achilles, whose torso is still suffused with brilliance from inside.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Ozymandias at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining symbolism in this and other poems.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Shelley’s poem? What do you think is the symbolism of the giant statue? What are your impressions of the endless desert landscape? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

I just wanted to thank you for your beautiful analysis and literate, comprehensive but accessible style. I have bought your excellent bundles before and as an English teacher fund them absolutely excellent but also as a Literature nerd myself I love reading your beautiful words on these poems. Thank you.

Hi Nicola,

It’s great to hear from you again, thank you for your kind words. It’s lovely to know that my blogs are appreciated. Thank you so much for your support of the site and taking the time to write.

“The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed.” A very interesting line, especially the word ‘mocked.’ Does it mean to deride as in today’s usage or does it mean to make as in a mock up? “Them” would apply to the passions. But whose hand and heart are the author’s? Ozymandias would not deride his passions, but he would feed them with his heart. The sculptor could deride Ozymandias’s pretensions, but could not fuel them from his own heart. So what exactly does this line mean, do you think?

Hi Peter,

I’ve always struggled with this line. I originally read it to mean the sculptor’s heart fed his own desire to deride the ruler, despite any risk that might bring down on him. Perhaps his action required some bravery or audacity to pull off? But equally well, the line could be read as the sculptor deriding the heart that fed those passions. The ambiguity is hard to resolve for me. What do you think?

As a teacher of IGCSE English Literature, I am very pleased to have discovered your blog. I have introduced it to my colleagues, and my students, and we are all enjoying that rare find online: well-written essays about poetry!

The accompanying artwork is an excellent touch. I have noticed that students in particular appreciate the visual references.

Thank you for taking the time to write this message, Daniel. I’m so happy you appreciate not only the analysis blogs, but the accompanying visuals. I wanted to make the illustrations specific to the poems rather than use found-images. I’ll pass on your message to my long-time collaborators (Alicia and Alistair) who help me make the lovely artwork. Of course it takes a lot more time, but I think the results are worth it, and to read your words makes me happy we did it like this.