Isobel Dixon shows us that older really does mean wiser as she reminisces ruefully about her childhood.

“Born with the gift of lyricism…”

Clive James, poet

Isobel Dixon has said that South Africa remains essential to her life and writing. In this poem you can almost feel the thirsty dryness of her childhood home, the Karoo plains. Later she would move to the UK (first Scotland then London). First published in a collection called Weather Eye (2001), Dixon has described Plenty as a “narrative family poem,” and spoken about how she and her sisters ran wild when they were young; so it’s safe to assume there’s a lot of herself in a speaker who, luxuriating in a brimful bath, finds her thoughts transported back to those arid, drought-stricken plains.

When I was young and there were five of us,

all running riot to my mother’s quiet despair,

our old enamel tub, age-stained and pocked

upon its griffin claws, was never full.

[blur]

Such plenty was too dear in our expanse of drought

where dams leaked dry and windmills stalled.

Like Mommy’s smile. Her lips stretched back

and anchored down, in anger at some fault –

of mine, I thought – not knowing then

it was a clasp to keep us all from chaos.

She saw it always, snapping locks and straps,

the spilling: sums and worries, shopping lists

for aspirin, porridge, petrol, bread.

Even the toilet paper counted,

and each month was weeks too long.

Her mouth a lid clamped hard on this.

[/blur]

Please click here to read the whole poem.

[blur]

We thought her mean. Skipped chores,

swiped biscuits – best of all

when she was out of earshot

stole another precious inch

up to our chests, such lovely sin,

lolling luxurious in secret warmth

disgorged from fat brass taps,

our old co-conspirators.

Now bubbles lap my chin. I am a sybarite.

The shower’s a hot cascade

and water’s plentiful, to excess, almost, here.

I leave the heating on.

[/blur]

And miss my scattered sisters,

all those bathroom squabbles and, at last,

my mother’s smile, loosed from the bonds

of lean, dry times and our long childhood.

Begin by reading Plenty carefully to get a handle on the past-present structure of the poem. The speaker tells us in the first line that she’s looking back at herself as a child: When I was young and there were five of us. Her present position is far removed from her childhood, both in time and, presumably, place. We soon find out that her living situation was quite difficult. There was never enough of anything; she tells us amusingly that even toilet paper was counted and, like everything else, carefully rationed. As you read, listen to the speaker’s tone of voice: this is not simply a tale of terrible poverty or an unforgiving mother. I would say her tone is nostalgic, wry, perhaps a touch bitter or regretful in places – however, these feelings are directed mostly at herself and her childish failure to understand the truth of her mother’s sacrifices. She makes the admission not knowing then halfway through the poem. Everything we read is memory re-filtered through a belated adult understanding, a distorted reality made clear by the wisdom that comes as one gets older.

Her present-day situation is markedly different to the situation she enjoyed and endured as a child. The delineation between past and present is clearly marked at the start of stanza seven: now. The poem creates strong contrasts between then and now: ‘scarcity’ vs ‘plenty’; ‘dry’ vs ‘wet’; chaos vs ‘ease’. These contrasts are achieved most often through diction: dry dams is opposed by cascade; stretched and never full opposes water’s plentiful; an inch turns to an excess of water. The final juxtaposition is quite poignant: five of us becomes scattered sisters. I get the impression, particularly given her admission I miss… all those bathroom squabbles, our speaker is quite lonely now.

An interesting theme the poem explores is how the past impacts upon the present, and how much of one’s childhood experience is carried into adulthood. The most pressing impact on her life was privation – she felt she never had enough of anything. Has having to go behind her mother’s back all the time to sneak biscuits and the like given her a bit of a guilt complex? Look at the language she uses to describe herself as a child: it’s like she was a little criminal. In her own words she variously swiped biscuits, stole water, snapped locks, and ran riot. She thinks of the taps on her bath as old co-conspirators, personification turning them into her partners in crime. When she describes herself in the present, her use of language isn’t much better. Now she is in a situation where she has enough of everything she needs, she feels guilty about that too! The key word is sin; others can be linked back to this guilty feeling: lolling connotes laziness; a sybarite is someone who takes pleasure from luxury; excess connotes greed. The image of her completely submerged by bathwater (bubbles lap my chin) contains all of these sinful connotations too.

Ironically, as a child her memory is actually quite full of ‘plenty.’ Examine the diction closely and you’ll find plenty (no pun intended) of words used to describe hardship that also suggest, well… plenty: for example, the dam leaking, if looked at another way, could suggest overflowing; describing the long dry season as an expanse of drought is a clearer one. The poem ends with the phrase long childhood, the sense of surfeit compounded by long assonant O sounds. Other words pop up: dear; plenty; full; fat; disgorged. Admittedly, some of these examples are negated e.g. never full, too dear. But the effect of so many words from the lexical field of ‘plenty’ is undeniable. The following lines, with all their surfeit of luxury, actually come from her childhood memories, though a careless reader would be forgiven for mistaking them with the present time:

up to our chests, such lovely sin,

lolling luxurious in secret warmth

disgorged from fat brass taps

Her present-day self is able to acknowledge the only reason she could experience luxury as a child was because of her mother. This patient, stoic woman protected the family from hardship as best she could, often through strictness and bean-counting that must have been frustrating for a small child. It’s tricky to see because of punctuation, but the simile Like mommy’s smile compares the windmills stalling and the dry dams to her mother’s pained, stretched expression. This association of her mother with the arid, dry landscape is a powerful expression of her protective instinct, as if she absorbed all the hardship and privation into herself rather than expose her children to all her worries: the spilling, the gradual depletion of day to day items, the constant tallying up (sums) of what can be used and what must be stored:

the spilling: sums and worries, shopping list

for aspirin, porridge, petrol, bread.

Listing words and using commas to mark the list is a structure called asyndeton; here, it creates the impression that everything is, drop by drop, slowly dribbling away or that the mother’s life is a list of worries. Contrast may be the defining feature of Dixon’s poem: she deploys it again to emphasise the mother’s stoic patience when faced with the wildness of her children. Running riot contrasts with anchored down; chaos opposes clasp; she clamped down on all the snapping and spilling. Read the poem aloud and you should be able to hear their rambunctiousness implied by sounds: running riot; snapping and spilling; skipped and swiped; lolling luxurious. The alliterative pairing of words energises the children’s actions.

A brilliant metaphor is her mother’s smile described as a lid or clasp that shuts all these troubles inside her and away from her children. To ‘keep a lid on it’ is an idiom that means not to speak the truth out loud. Of course, understanding that depends on one’s perspective: the young speaker felt she was locked in; her older, wiser self knows that her mother was hiding their desperate situation and taking on all the responsibility for the family. How successful she was is left for us to infer, though it is hinted at through the stanzaic form of the poem. Written in roughly equal quatrains (verses of four lines each), the regularity of form suggests the mother organized things effectively, passing this ability onto her daughter too, who seems to be quite successful. This belated understanding is suggested through a further metaphor: anchored down connotes stability in uncertain waters and the recognition that her mother was an essential lifeline.

We haven’t yet examined the bathtub, the central symbol by which we can compare the past and the present. Griffin claws decorating the feet of the tub elevate its status through association with classical mythology and signal its symbolic status right off the bat. Age-stained and pocked don’t unduly detract from this: the tub carries a kind of faded glory in the mind of the speaker, like an ancient monument whose head is eroded by rain and time but whose feet are still in an original condition.

Associated with the tub is, of course, water, with all its life-giving and vital connotations. Dixon uses water as a motif for time passing, hardship and luxury; water is the element that runs through the whole of the speaker’s life. Even an extra inch of water is described as precious. Words related in some way to water appear everywhere, sprinkled through the poem like stray droplets from a shower: running; tub; stained; leaked; anchored; spilling; toilet; shower; cascade; and belatedly too, water. Here too is where the form of the poem really comes into its own. Composed mostly of loose iambs and almost always featuring enjambment from line to line, and even verse to verse, the stanzas seem to ‘overflow’ and words ‘trickle’ from one line to the next. Enjambment creates other effects too: the way the sentences are out of sync with the stanzas suggests dissociation between the speaker’s past and present selves.

Because, at the end of the day, that’s what the poem is really about: how time and circumstance interact with memory to change how you view yourself and your place in the world. For Dixon’s speaker, I feel like it came just a little too late – her mother is absent from the ‘now’ section of the poem. The implication is that the spoiled girl in the bubbly bathtub never got to say ‘thanks’ or show her appreciation for the sacrifices she made to keep the family going. She acknowledges that her mother was as much a prisoner of circumstance as her and her sisters by returning to her mother’s smile, now released from the bonds of lean, dry times. There’s something about the phrasing here – is it the word released? – that suggests her mother is no longer alive.

In a poem in which water played such a huge part, it’s ironic that the final image is made of the words lean, dry times. It’s hard to escape the feeling that, despite having every luxury, the speaker could as easily apply those words to her life in the present as she did to the past. Looking back, she now realises she had plenty of everything after all.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Blessing by Imtiaz Dharker

Set in India, this poem summons the image of an arid, dry landscape, parched – till the water pipe in the town square suddenly bursts, with joyous consequences.

- Those Winter Sundays by Robert Hayden

Like Dixon’s poem, Hayden’s sonnet reaches out across time and space to reconcile with his father whose actions he could not understand when he was just a young child.

- The Dry Salvages by T.S. Eliot

Across five sections, Eliot’s poem offers his meditative thoughts on water in all its forms and symbolisms.

- Stagnant Water by Wen Yiduo

This is an entirely different take on water; rather than life-giving, it is stagnant and ‘hopelessly dead.’ Assassinated in 1946, Yiduo’s poetry has been praised by both Chinese commentators, who have likened a poem of Wen Yiduo’s to a jewel, and those from elsewhere who love the vernacular style of his writing.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Plenty at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

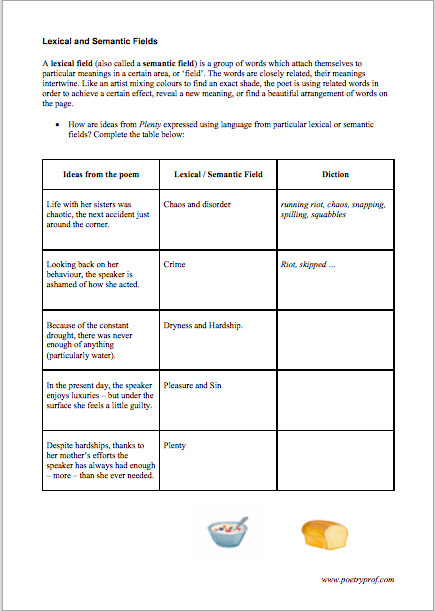

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on diction (reiteration, synonyms and lexical fields)

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this commentary about Plenty? We hope you found it entertaining and useful. Do you agree that the speaker seems to look back on her past with regret? Did you find the end of the poem poignant as well? Why not leave a comment, start a discussion or share your ideas in the space below? And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Your analysis gave me a very clear understanding of the poem, it is helping me a lot as I am revising for my IGCSE English . However, I am still having trouble understanding stanza 7. Could you please do a deeper analysis on stanza 7. Thank you.

Hi Alyssa,

Thank you for your comment. I’m glad you like the site and are finding it useful.

You should look to see how stanza 7 contrasts with stanzas 1 – 6, especially in terms of the descriptions of water. Did you notice it starts with the little word ‘now’? What does that tell us? You should make sure you know the word ‘sybarite’ too – it means, ‘one who indulges in pleasure.’ You might want to find some words from stanza 7 which suggest how good the speaker’s life is ‘now’ – then keep reading into stanza 8 and ask; if life’s so good, why doesn’t she seem happy?

Good luck with your IGCSE revision. I hope Plenty comes up in the exam for you!

Alyssa hi i was wondering it is a year later what did you get for your IGSCE english and what specification did you do?

You could find past papers online…it helps with 9th and 10th-grade exams!