Edward Thomas’ not-quite-a-war poem inspired by a tempestuous downpour.

“The man with the keys to the Paradise of English poetry”

The Times of London

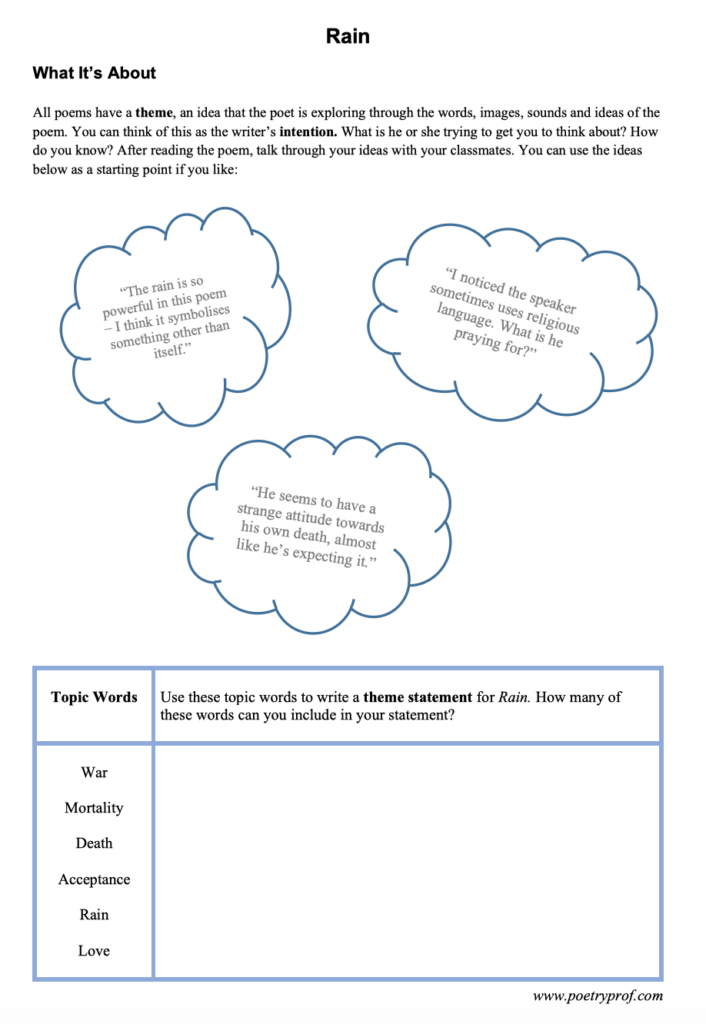

Edward Thomas, born in 1878, lived only to the age of thirty-nine when he was killed during the First World War, at the Battle of Arras in 1917. When I first read his poem Rain, it felt like it had been written by a much older writer. The poem has a world-weary cynicism and bleak pessimism that seems too strong in someone so young. But Thomas wrote all his published poetry between the years of 1914 and 1917 so, while his poetry rarely tackled the subject of war directly, he was certainly inspired by his experiences before he was sent into battle. In 1915 he volunteered for the army as an infantryman, and wrote this poem from Hut 51 in his training barracks (the bleak hut that he mentions in line two). Soon he will arrive at the front lines and would die a year after this poem was completed (he did not live to see his work published). As he writes, persistent rain patters down, and he uses the weather to set the maudlin mood of his poem, as the poem’s central symbol, and its most important structural device.

Rain, midnight rain, nothing but the wild rain On this bleak hut, and solitude, and me Remembering again that I shall die And neither hear the rain nor give it thanks For washing me cleaner than I have been Since I was born into this solitude. Blessed are the dead that the rain rains upon: But here I pray that none whom I once loved Is dying to-night or lying still awake Solitary, listening to the rain Either in pain or thus in sympathy Helpless among the living and the dead, Like a cold water among broken reeds, Myriads of broken reeds all still and stiff, Like me who have no love which this wild rain Has not dissolved except the love of death, If love it be for what is perfect and Cannot, the tempest tells me, disappoint.

While he did not write any poetry until 1914, Edward Thomas had written about rain symbolically in prose before. In his 1909 The South Country, a collection of writings about a year he spent wandering through rural counties such as Kent, Hampshire and Cornwall, he wrote: ‘At all times I love rain, the early momentous thunder-drops… It does work that will last as long as the earth. It is about eternal business. In its noise and myriad aspects I feel the mortal beauty of immortal things.’ In 1913, he wrote about rain once more, and it is interesting to note how different the rain feels a mere four years later:

I lay awake listening to the rain, and at first it was as pleasant to my ear and my mind as it

The Icknield Way, 1913

had long been desired; but before I fell asleep it had become a majestic and finally a terrible

thing, instead of a sweet sound and symbol….

In his biography of Edward Thomas (Now All Roads Lead to France – The Last Years of Edward Thomas) writer Matthew Hollis argues the link between The Icknield Way and Rain, explaining that this passage is about a storm Thomas was caught in in 1911, a deluge so fierce it drove him to shelter in an inn in a village called East Hendred. Hollis writes how: ‘He lifted his face to the window… but there was nothing out there but the darkness and the thick black rain.’ As he huddled alone, feeling parted from nature and the world, he even heard a voice from the rain speaking to him like ‘a ghostly double’. Perhaps, on this portentous night, the seeds of his poem were sown.

The rain is first described as wild so we should imagine a storm that’s lashing trees, forming huge puddles outside, and drumming loudly on the roof of his wooden hut. The rain is persistent. There may be some lulls, but it picks up again and by the end has become a tempest, which is an extraordinary storm of driving rain and strong winds. This power is implied through repetition (three times in the opening line alone; eight times in whole the poem – nine if you include the title) leaving us in no doubt as to the sogginess of the scene. At one point the word is repeated immediately, with no intervening words: Blessed are the dead the rain rains upon. Repetition helps bring to life the movement of the rainstorm as we read through the poem: at times the storm abates a little, at other times it intensifies. Overall, the constant rain creates a maudlin, bleak mood for Thomas’ poem. Also called atmosphere, mood is defined as the feeling a poem creates for the reader. We are intended to feel sad and melancholy, a mood created by images of a lonely man, in his bleak hut, surrounded by swirling, incessant rain.

You might be familiar with the film trope that, when a hero suffers defeat, a loved one dies, or a break-up occurs, it just happens to be raining in the background. This is no accident. The film makers are actually employing a literary trope known as pathetic fallacy, which can be understood as the transfer of emotion from the natural world onto the human character. In this poem, rain isn’t simply part of the background, it mirrors the emotional state of Thomas’ speaker and even interacts with him several times, such as when he feels like it’s dissolving all his memories of love. The connection between rain and death, and the possibility that he might die at any moment, is incredibly potent. The rain affects his thoughts, so he’s remembering again that I shall die, bringing his mortality into sharp focus. Shall is an example of a modal verb, little words that reveal degrees of certainty and probability (‘might’ is not at all certain; ‘shall’, ‘must,’ and ‘will’ are on the strong side). As Thomas wrote these lines the whole of Europe was being wracked by a conflict that would eventually kill millions, so it shouldn’t be surprising that death felt inevitable to him. In fact, you might get the subtle impression that he has already begun his journey into death. Repetition, this time of solitude/solitary, isolates Thomas inside an empty grey zone. While his soldier’s barracks should be full of people, bustle and noise, he writes as if he’s alone, hearkening back to that night in 1911 when he was trapped in a lonely inn by the storm raging outside. Therefore, the bleak hut is neither here nor there, but becomes a kind of waystation, or No Man’s Land, between the realms of the living and the dead. There’s no description of the surrounding landscape, so it feels like the rain is an impenetrable curtain, sealing him away inside this otherworldly cabin. Every time he uses the word solitude/solitary, even at the start or in the middle of the line, he marks it with punctuation. Called caesura, these punctuation marks isolate the word solitude (or solitary) from the rest of the lines, making the speaker seem that little bit more alone.

That’s not to say that the rain, loneliness, or even death, are straightforwardly hostile forces. When Thomas thinks of the hundreds and thousands of young men already buried in the battlegrounds of Europe, he says that Blessed are the dead that the rain rains upon. In this case the rain, like death, brings relief to pain and suffering. The line is a clear echo of ‘Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth’ from Matthew (verse 5): connected to Christian baptism rituals and the washing away of sin, water often has a cleansing and purifying power, and Thomas can physically feel this healing effect when he says it washes me cleaner. Read this line carefully once more and you’ll see he’s not saying he feels the cleanest he’s ever been, but since I was born into this solitude, referring to his being an enlisted soldier. The sense of his bleak hut as a kind of purgatorial limbo is once again palpable, as if by choosing to go to war (Thomas actually volunteered for military service in 1915) he’s abandoned his old life and been reborn into a new one. Notice how he writes about love in the past tense (none whom I once loved) and, later, admits to losing his capacity for love. Stuck in this liminal zone, knowing he is soon to be sent to the hell of the trenches, the rain helps smooth the transition from life to death, and perhaps even absolves him in advance of the sins he may have to commit once he is sent into battle.

Listening to the rain has the contrary effect of drawing him emotionally closer to others, even as it physically separates him from humanity. The rain evokes the idea of sympathy, which means being able to relate to the thoughts and feelings of others. He imagines those he once knew in an identical situation to himself, lying awake and contemplating their own mortality. Thoughts like this may seem hysterical, but it’s important to remember the long shadow war was casting. The First World War saw carnage unleashed on a scale never before seen, resulting in the deaths of millions of people. He prays that none whom I once loved is dying to-night, and also prays that they are not as bound up in their own psychological fear and pain as he is himself. However, the internal rhyme between rain and pain, as well as repetition of dead and dying, begin to firm those symbolic associations between the rain and Thomas’ sense of death approaching. He therefore concludes that individual people are helpless in the face of unavoidable forces as devastating as war and death. Here, Thomas’ use of enjambment really pays off. As he flows lines of poetry one into another, he chooses certain words that have powerful meanings as headwords (words that begin lines of poetry). Placing the word helpless at the beginning of a line gives it that little bit extra significance. This moment is a definite turning point in the poem; from here on he is certain that he will die soon.

Therefore, the rain is a murky, ambiguous symbol. It ebbs and flows, here abating, there rising like floodwater. After acknowledging the essential helplessness of people, Thomas describes an image of the rain settling into pools of cold water among broken reeds. He dwells for a moment on the reeds, describing them as myriads of broken reeds, as if an uncountable number lie in the mud, and as still and stiff, words that can equally be used to describe corpses as broken branches. When he personifies reeds, comparing them to himself and saying that they too once knew love, the reader is left in no doubt that the reeds symbolise the broken bodies of soldiers, the youth of an entire generation, strewn across European battlefields. In a poem that doesn’t rhyme, those moments of internal rhyme (dying/lying in line 9) combined with the heavy alliteration of still and stiff serve to emphasise the disturbing thoughts that are troubling Thomas. If you’re interested in exploring the religious dimension of the poem further, reeds are an important biblical symbol, described as ‘withered’ and ‘driven away’ in Isaiah and mentioned in many other places besides: ‘The paper reeds by the brooks… shall wither, be driven away, and be no more.’ This biblical allusion helps augment and enhance the baptismal power of the rain as suggested earlier in the poem. Natural symbols, including reeds, rain and water might imply that the process of dying is a natural one, but Thomas lives in a world where death was unnaturally brought to an entire generation of young men, and he seems to be struggling to resolve this contradiction in his own mind.

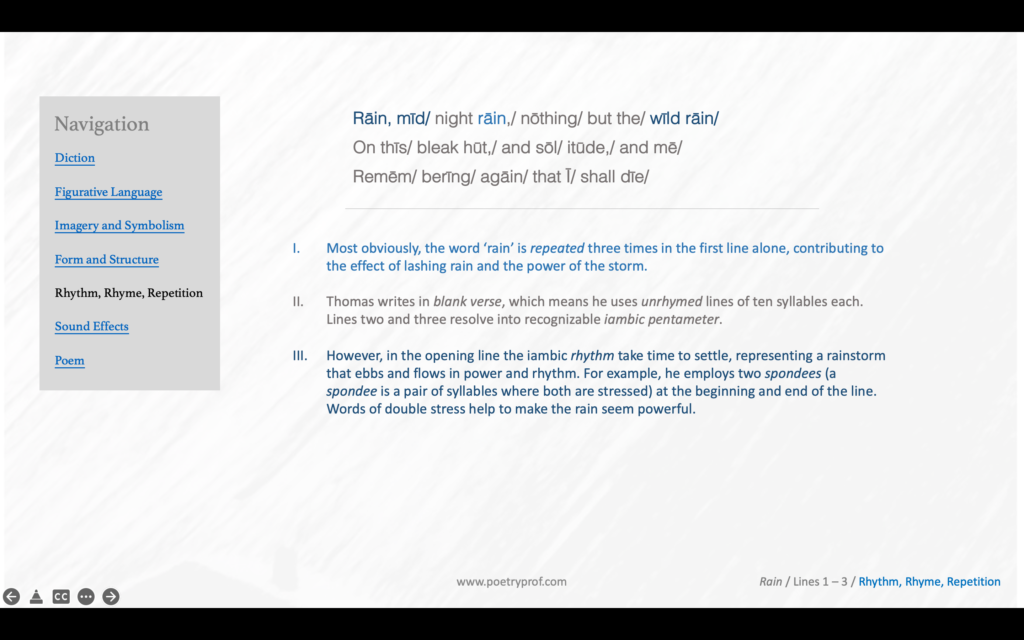

The recent mention of rhyme reminds me, we should take a minute to appreciate some other formal elements of the poem and appreciate the mastery of his craft demonstrated by Edward Thomas, despite his relative inexperience with writing poetry. Like many poets writing at the turn of the twentieth century, Thomas wrote in blank verse, which means his poem is made of unrhymed lines of ten syllables each. Blank verse is traditionally written in iambic pentameter, meaning those ten syllables are arranged in pairs which create an unstressed-stressed rhythm. You can see this for yourself in lines presented with iambs marked out:

On thīs/ bleak hūt,/ and sōl/ itūde,/ and mē/ Remēm/ berīng/ agāin/ that Ī/ shall dīe/

However, the poem doesn’t easily settle into an iambic pattern. To begin with, Thomas employs a rhythmic measure called a spondee, whereby the first two syllables of the poem are both stressed, giving his rainstorm even more kick. Look how both the first and last measures of this line contain double-stresses:

Rāin, mīd/ night rāin,/ nōthing/ but the/ wīld rāin/

Later, he mixes in one or two less conventional feet into the blank verse mix in order to suggest the unsteady swells of the downpour. In line five, for example, two quick anapests mimic the quick pitter-patter of lighter rain before the steady iambic rhythm reasserts itself. An anapest is defined as a measure of three syllables in an unstressed-unstressed-stressed pattern. In musical terms, the rhythm is briefly quickened, so it sounds like two quavers and a crotchet:

For wāsh/ ing me clēa/ ner than Ī/ have bēen/

Twice, he calls the rain wild, and so it is. You have probably already seen for yourself the very rare use of punctuation at the end of each line. In the first six lines, for example, only the last is end-stopped; all the other lines enjamb down the page like water sluicing down the side of his hut. Generally, he uses enjambment throughout the poem to imply the persistently falling rain while irregularities in rhythm suggest quiet lulls or sudden lashings. Occasionally, the rhythmic pounding of the rain seems to echo the bombs and bullets pummelling a war-torn landscape into mud and blood, especially when combined with hard alliteration such as but… bleak where the repeated B creates a distant percussive boom.

Over time, the rain has an erosive effect on Thomas’s speaker, much like running water would gradually wear down a landscape. He admits that he is losing his capacity for love: have no love which this wild rain has not dissolved. The word dissolved stands out as metaphorical, creating the effect of the rain wearing him away – or sharpening him to a point by stripping him of any extraneous or unwanted emotions, like sympathy and love, which have no place on the battlefield. Is he purposely hardening his mind against love so he can accept the probability of his own death? It’s almost like he wants the rain to wash away any distraction so he can face what must come with a strong resolve. He allows the rain to erode him down until only one thing remains: except for love of death. This is the moment he embraces the certainty of his own death and refuses to imagine any other outcome.

While this may seem unduly fatalistic, keep his situation in mind; he’s preparing himself to be thrust into the midst of some of the most brutal battles ever seen on our planet. His death is a very real possibility; tragically, the very next year (1917) would see him die in the Battle of Arras. The rain’s final message confirms to Thomas that, of all the things to hope for, death is the only certain and inevitable one. This is why he calls it perfect: at the end death is the only thing that cannot… disappoint. There’s a rise in intensity at the end of the poem: Cannot is another spondee giving his conclusion the weight of certainty. Mixed with strong alliteration and consonance using the letter T (Cannot, the tempest tells me…) the final line is both the storm at its height and Thomas at his most resolved. He has certainly transformed over the course of the night. At the beginning of the poem he could neither hear the rain; now the personification of the rain is clear, its voice has gotten through to him, and his ears are open to receiving its messages.

Although I’ve constantly referred to the historical context of this poem, I don’t want to over-egg the war pudding because, even without this knowledge, the poem functions perfectly well as a lament on approaching death, loneliness, and sadness, all evoked by the sounds and images of the deluge. If Matthew Hollis is right, the seeds of Thomas’ poem were sown way back in 1911, when he was marooned in the night by a storm that seemed to cut him off from the world, a downpour in which he felt he ‘was drowning and returning to the darkness; the rain was taking away the gift of life he had never truly grasped’ (Hollis). In contrast with many early twentieth century poems that used lofty diction, Rain is written in simple, everyday language that speaks to all of us about thoughts we might have when we’re sad or contemplate the idea that we won’t be around forever. The fear that one is ultimately alone at the end of one’s life is very real for many people, and Edward Thomas is not the only one to have expressed this universal truth in poetry.

(This blogpost was massively improved with the help of reader Matt Smith, who not only pointed out the biblical allusion of broken reeds, but also shared passages from The Icknield Way and introduced Thomas’ biography to me. Thanks Matt!)

Suggested poems for comparison:

- This is No Case of Petty Right or Wrong by Edward Thomas

Most of Thomas’ war poetry didn’t mention the war directly, but this poem is an exception. As a man who volunteered for military service in 1915, Thomas presents an argument for going to war that moves beyond the simple propaganda of the time.

- Nearing Forty by Derek Walcott

Like Thomas, Walcott is awake at night listening to the sound of rainfall in the roof. It prompts in him a kind of crisis, as he worries that he is running out of time to perfect his writing so it’s as pure as the rhythms and sound of the rain.

- Rain by Sean O’Brian

If you want to hear how another writer can bring rainfall to life in poetry, look no further. Read the second and third lines out loud and try to hear the beats falling down the page for yourself.

- Exposure by Wilfred Owen

The First World War robbed us of many young writers, such as Edward Thomas, who could have gone on to create so much more. Wilfred Owen is one of the most famous young writers killed in action in 1918 at the age of only 25.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Rain at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining blank verse and pointing out rhythmic variations in Thomas’ poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Edward Thomas’ poem? What does the persistent rain symbolise to you? Can you recommend other war poems, or poems written in blank verse? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.