Adrienne Rich’s mysterious poem suggests we all have something to make up for – but what?

“A poet of towering reputation and towering rage”

Margalit Fox, Senior Staff Writer, NYT

Every so often, you’ll come across a poem that leaves you baffled. Amends is this poem for me. Beautifully written, full of striking images and poignant moments, the meaning of the poem remains stubbornly elusive. And that’s a great reminder: not every journey has to have a map; not every meal has to follow a recipe book. As Rich herself said on receiving the National Book Award in 2006, ‘Neither is it a blueprint, nor an instruction manual, nor a billboard.’ Sometimes, poking and prodding and seeing what you can come up with, or wandering about with no idea where you’re going, can bring unexpected delights. Poetry isn’t about figuring out what things ‘mean,’ and poems rarely have ‘morals’ attached to the end. One of the exciting things about a beautifully-written poem is that two readers can have wildly different experiences and understandings of the same words. So, before you head into my ideas about Amends, read it to yourself and spend time with the words, alone; let yourself wander in Rich’s eerie, deserted landscape and wonder what the poem means to you:

Nights like this: on the cold apple bough a white star, then another exploding out of the bark: on the ground, moonlight picking at small stones as it picks greater stones, as it rises with the surf laying its cheek for moments on the sand as it licks the broken ledge, as it flows up the cliffs, as it flicks across the tracks as it unavailing pours into the gash of the sand-and-gravel quarry as it leans across the hangared fuselage of the crop-dusting plane as it soaks through cracks into trailers tremulous with sleep as it dwells upon the eyelids of the sleepers as if to make amends.

Amends thrives on ambiguity, the space between Rich’s creative impulse, her pen, and your imagination. Ambiguity can sometimes be threatening or fearful, especially to readers who prefer their literature to say straight out what it means. When encountering ambiguity, it’s all too tempting to say, ‘I don’t get it’ or ‘it could mean anything.’ But recognising ambiguity doesn’t mean that anything goes. The words and images of the poem present a range of interpretive possibilities – but these interpretations should still be firmly anchored by those words, what they mean and connote, and the clarity of the images they create.

Nowhere is this lesson more important than when considering the opening few words, which are actually a literary allusion, a subtle reference to knowledge outside of the poem. Allusions can be classical, cultural, historical or literary: Nights like this is a literary allusion reminding us of William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, in particular Act 5 Scene 1. Lorenzo and Jessica are in the garden of their friend’s house in Belmont, a magical place where dreams come true and where romance and wonderful possibilities play out under the light of the moon. In this scene, Lorenzo tries to seduce Jessica and she, uncertain of her feelings for him, rebuts each of his advances. As they trade wordplay, each line begins with the phrase On a night like this. For those who recognise the allusion, the mind instantly connects Rich’s poem with this moonlit scene and its subtext. Lorenzo was using the words to mean, ‘On a night like this anything is possible.’ However, Jessica is a Jew who, in order to escape from her overbearing Father, Shylock, converted to Christianity and eloped with Lorenzo. You might imagine that the end of the play is a time for the two of them to celebrate the success of their daring plan and fall into each others’ arms. Instead, Jessica deftly evades Lorenzo’s obnoxious chat-up lines and hesitates over his lewd proposals. Her replies suggest she harbours doubts and starts to see Lorenzo for the smug, artless boor he really is. The fear she may have made a mistake is left unspoken, but is tangible nevertheless.

Alluding to Jessica’s story weaves the notion of making amends, which means ‘to make up for some wrongdoing,’ through the whole poem. You probably noticed that Amends is bookended by this word; it is both the title and the final word, suggesting everything in between is an attempt to make up for some kind of transgression and put right some unseen wrong. The name for the structure of a poem that ends where it began is loop composition, which also has the effect of suggesting nothing has changed. No amends have been made, no mistake rectified. What that mistake is, is left deliberately ambiguous. The poem is full of vague hints and faint suggestions, but never resolves those fuzzy images into a clear target for us to aim at. What is clear is the inactivity of the people in the poem. Remaining unseen until the final stanza, the poem depicts people as sleepers, inactive, eyes closed, either unable or unwilling to make amends for themselves. This is where the metaphysical moonlight that shines through the poem comes in. Could it be acting on behalf of the sleeping people, trying to do what they cannot or will not do? The light symbolizes the unspoken or unrealised desire of those sleeping people to make amends – but for what?

In order to intuit what this might be, you need to know a little bit about the setting of the poem and the writer. Adrienne Rich was an American poet (she died in 2012) who lived in Santa Cruz, California, and certain uses of diction, in particular the hangared fuselage of the crop-dusting plane, betray the modern American setting of Amends. There’s a strong sense of juxtaposition between details of the modern human world and a timeless, natural world: diction such as apple bough, stones, surf, sand and bark evoke natural materials and textures, and at one point a bud opening on the branch of a tree is described as a white star… exploding out of the bark in a way that evokes primordial images: supernovas and the birth of galaxies. By contrast, the modern day is glimpsed in train tracks, a sand-and-gravel quarry, the aforementioned plane, trailers. The turning point is the cliff: as the light flows up the cliff and across the tracks it seems to cross some kind of symbolic barrier between the purely natural world and one inhabited by people. Everything in the human world, though, has a faded or worn-out quality: the plane is hangared – unused – the ledge is broken, the light slips through cracks, and the word gash, used to evoke the dug-out crevice of the sand-and-gravel quarry, strongly implies that the land has been wounded. Knowing the history of how the American land was conquered, taken by force from indigenous people by the white settlers who now call it their own, might give us some clue as to why amends need to be made. Other possibilities simmer under the surface of the poem too; Rich was a lesbian, a Jew and a woman – triply marginalised, as her obituary in the New York Times points out. Throughout her life, then, Rich encountered plenty of things for which people could decide to make amends and you are free to hang your hat on any or none of these ideas.

The most important feature of the poem, in this regard, is personification. For a brief moment, in stanza two, the moonlight behaves exactly like a hunter searching for his unseen quarry. Firstly, the light is described as picking at small stones as if looking for traces of something passing by; then we see it laying its cheek for moments on the sand in the manner of an historical hunter listening for the pounding of distant buffalo feet transmitted through the ground. The cumulative effect of these personifications, while ambiguous, faintly suggests the vanished native American people. The spirituality of this culture is nicely evoked by the spirituality of the poem, suggesting the moonlight could be some kind of spirit guide, doing nothing more than encouraging modern people to remember their own history as a first step toward making amends. Remember, though, there are many possibilities offered up by Rich’s poem, all deliberately ambiguous; there is certainly no requirement for you to agree with this interpretation.

In fact, despite the clear and obvious personification in the examples we’ve just discussed, you shouldn’t overegg the personification pudding. The image of the native American hunter is strong but fleeting, vanishing like those forgotten tribes. As the light roams across the land, it sometimes behaves exactly how you would expect light to do, at other times more like water. The way it rises with the surf aligns the light with the rolling swells of the ocean; it flows up the cliffs in a watery way, and then pours itself into the dug-out crevice of a sand-and-gravel quarry as if trying to fill it up. To my mind, it’s less important to try and figure out what the light is meant to be; rather just luxuriate in the enjoyment of Rich’s graceful and sensuous descriptions. As it rises with the surf it seems to be swollen in size and power: but the next moment it licks and flicks its way across the tracks, giving it a light, almost furtive quality. The way the light seems to shapeshift between the lines is both eerie and beautiful. Amongst all the descriptions of the mysterious light unavailing stands out. Meaning ‘helplessly’ or ‘uselessly’, this diction reminds us that the light itself doesn’t have any real power. Poetically, remember, it is just a symbol for the need to make amends, a need that the people sleeping in the trailers seem to have forgotten. The moonlight acts in vain, unavailingly trying to fix the broken things in the world that people have left behind.

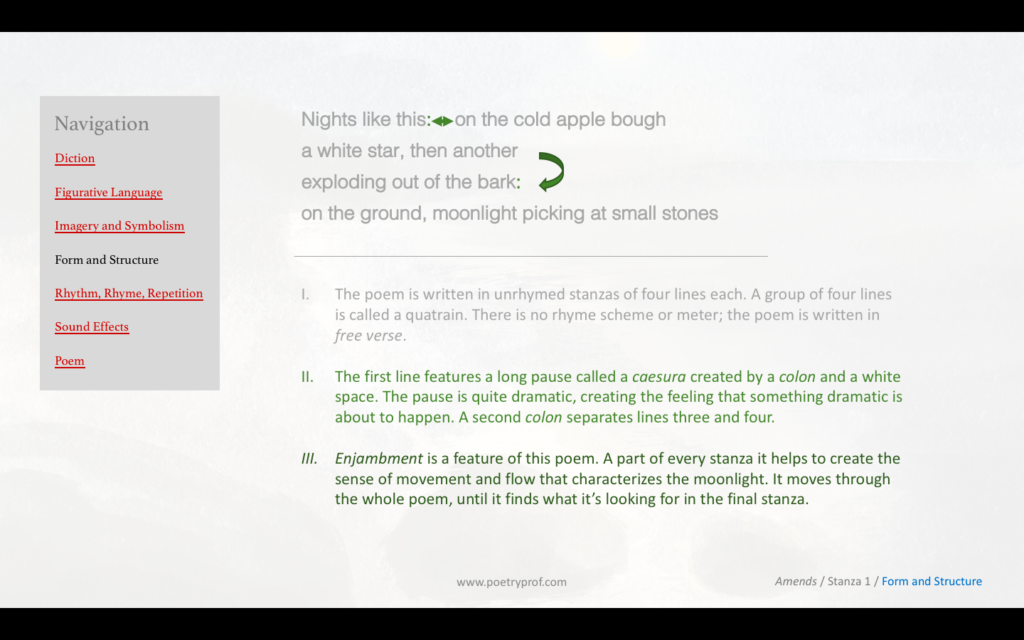

Whether you think the light represents the spirits of the forgotten ancestors of the land, or whether it’s more like an unseen force of nature, or even something else entirely, there’s a palpable sense of urgency running through the poem, as if the light has only a limited time to fulfil its quest. This urgency is created partially through aspects of form; there are no full stops or capital letters to break up the lines, and the poem liberally uses enjambment – lines of poetry that run one into the next and even flow uninterrupted from stanza to stanza – to create the sense of urgent, fluid movement. The pace of most of the poem is in marked contrast to the opening. In fact, three caesuras (a caesura is a deliberate break or pause in the middle of a line of poetry) ensure the first stanza sets off at a glacial pace, bringing to mind the eons of time between the creation of the universe (that white star exploding) and the modern age of humanity. The first caesura is a colon followed by large white space in the first line, a space that seemed to hint at possibilities for anything to happen. Then a second colon at the end of line three creates another sizeable pause.

After this slow start though, the poem explodes into life. As the moonlight sets off on its mysterious search, the poem gathers more and more momentum. Anaphora – the repetition of as if at the beginning of each line, combined with the aforementioned enjambment – runs the lines swiftly and smoothly from one into the next. Small stones morph into greater stones; verbs (picking, lying, rising, flows, licks, flicks, pours, leans and soaks) come thick and fast. Uses of alliteration, particularly in the second stanza (flicks and flows is one, as is the sibilant S in flicks across the tracks) are quick and light, the sounds of the poem skipping lightly through the lines, not disturbing any of the items or objects it comes across. Internal rhyme (picks… licks… flicks) works in combination with consonance (the repetition of sounds that are not necessarily at the beginning of words is called consonance, like the flickery CK sounds underlined here) to compound this effect. Rich writes in the present tense too, adding a sense of immediacy to the poem; the light roams here and now, right in front of our eyes. It isn’t until the word leans, when the light seems to peek furtively around the abandoned hanger, soaks, and finally dwells, when the moonlight dwells on the eyelids of the sleepers in the final stanza, that the poem slows down and we can all catch our breaths. This slowing-down creates the impression that the moonlight first approaches, then finally finds, what it has been looking for.

It should be no surprise that the answer lies with people. The final stanza confirms the idea we’ve had ever since that word unavailing that the moonlight, whatever it may represent, doesn’t have the power to make amends for us. Another small clue is as if in the final line. As if means ‘like’ and is the signal for a simile, something that is not actually real. Only people – not light, however supernatural it may be – have the ability to make up for their wrongdoings. The word tremulous means ‘shaking’ or ‘quivering,’ hinting that there’s something going on behind those eyelids after all. The moonlight illuminates the eyes of the sleepers flickering in REM sleep in such a way as to suggest the light could be a dream-projection, or a manifestation of a subconscious desire.

With this final image, the poem raises the question of how willing the sleepers are to begin making amends for the events and mistakes of the past, large or small, whatever they may be. The first step of any healing process has to be to face the truth by opening our eyes. Once acknowledged, moreover, without human action, desires and intentions – however well-meaning – remain unacted upon and unfulfilled. I think there’s a pretty obvious suggestion that we are all sleepers; after all, we all of us live somewhere in the modern world that is built upon the bones of the past. Whether we acknowledge this truth by opening our eyes to the events of history, or whether we decide to just keep on sleeping, is only for us to choose.

Suggested poems for comparison

- Frost at Midnight by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Like Rich’s magical moonlight, the elements in this poem are imbued with a mysterious power that plays in the world while people sleep.

- What Kind of Times Are These by Adrienne Rich

In this ghostly and disturbing poem, a woman inhabits a ghostly half-realm, where people disappear and everything is fading. It shares an eerie atmosphere with Amends, making this poem an interesting counterpoint to today’s.

- Moonlight by Paul Verlaine

Translated from French, this delicate and poignant poem evokes moonlit scenes of dancing and carousing – but the end is curiously muted, suggesting that all good things must soon end.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Amends at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

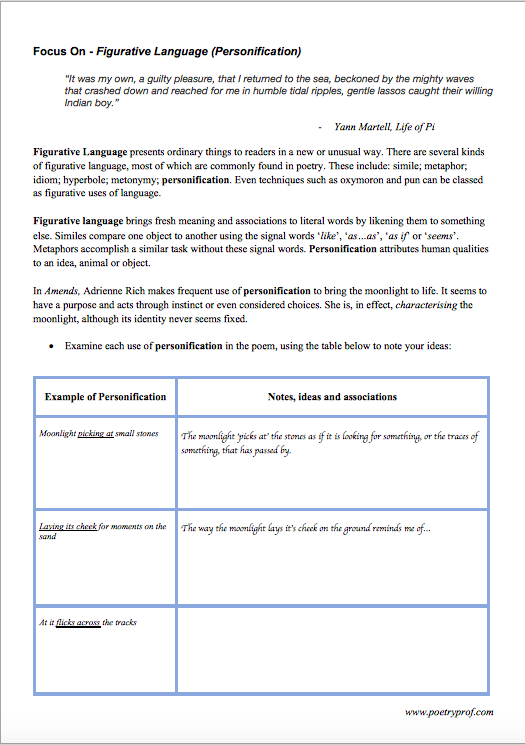

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on examining personification.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for revision or a recap lesson.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Adrienne Rich’s poem? Do you agree with our ideas about the symbolism of the moonlight? What do you think the sleeping people should be making amends for? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Fantastic resources. Thank you

Caesar loved this poem so much!

No u 😀

You cannot begin to imagine how thankful I (and my igcse grades) am for you PoetryProf!! I love your interpretations of any poem, and it really gets me thinking more “out of the box”. I started liking poetry a while back now, but reading about how poems can say so much with perhaps so few words, amazes me! You inspired me to start writing more poems, and I’m so grateful for that.

THANK YOU:))

Hi Dodo,

Thank you for your kind words. I’m very happy that this blog was able to help and even inspire you. I’m also pleased for your IGCSE grades! Hope you keep loving reading and writing poetry.