Take a drive through Margaret Atwood’s sinister suburban poem to find out who the City Planners are – and what they really want.

Atwood is… acutely aware of the problem of alienation, the need for real human communication and the establishment of genuine human community—real as opposed to mechanical or manipulative

Gloria Onley, West Coast Review.

You may have heard of Margaret Atwood thanks to the success of the television adaptation of her most famous novel, The Handmaid’s Tale. This novel was published in 1985 and presaged the release of other works of speculative fiction exploring dystopian near-futures during and after environmental catastrophe: Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood, MaddAddam. This theme is at play in today’s poem too, in which the gridded, orderly blueprints of our towns and cities are designed by a sinister cabal of City Planners. While their built environments are superficially ‘perfect,’ laid out in straight rows and clean lines, they seem inimical to any sense of life, warmth, or community feeling. Atwood’s speaker, as she drives around one such city suburb with her family, feels like an unwelcome intruder. She doesn’t share the City Planners’ vision of urbanized utopia, the spreading of more and more concrete over the natural world. Buried far beneath the city’s solid veneer, Atwood’s speaker glimpses traces of the real, natural landscape that the City Planners are trying to hide. Suddenly her gaze shifts into the far future; after a huge environmental shift, the city has collapsed into the ground and a new ice age has returned. Yet still the City Planners pursue their mad quest to control not only the people who live in their dystopian cities, but the very landscape, the entirety of the natural world, as well:

Cruising these residential Sunday streets in dry August sunlight: what offends us is the sanities: the houses in pedantic rows, the planted sanitary trees, assert levelness of surface like a rebuke to the dent in our car door. No shouting here, or shatter of glass; nothing more abrupt than the rational whine of a power mower cutting a straight swathe in the discouraged grass. But though the driveways neatly sidestep hysteria by being even, the roofs all display the same slant of avoidance to the hot sky, certain things; the smell of spilt oil a faint sickness lingering in the garages, a splash of paint on brick surprising as a bruise, a plastic hose poised in a vicious coil; even the too-fixed stare of the wide windows give momentary access to the landscape behind or under the future cracks in the plaster when the houses, capsized, will slide obliquely into the clay seas, gradual as glaciers that right now nobody notices. That is where the City Planners with the insane faces of political conspirators are scattered over unsurveyed territories, concealed from each other, each in his own private blizzard; guessing directions, they sketch transitory lines rigid as wooden borders on a wall in the white vanishing air tracing the panic of suburb order in a bland madness of snows.

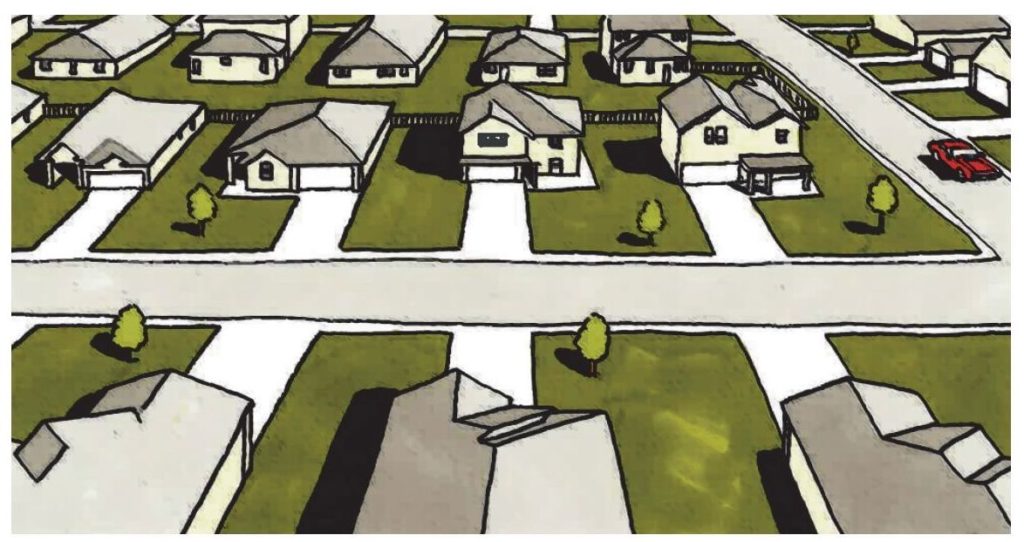

The beginning of this poem could be the start of an Alfred Hitchcock thriller or an episode of The Twilight Zone, where all the residents of an ordinary small town turn out to be in a devil’s cult or perpetrators of a secret cloning experiment. Something’s wrong… but you’d be hard pressed to put your finger on precisely what it is. The speaker of the poem is driving with her family (she says us in line three and our in line eight) around the residential streets of an ordinary suburban area; white picket fences, tree lined streets, driveways, and mail-boxes set up by patches of lawn. Atwood is a Canadian poet, so imagine any North American-style suburban town and you should be able to visualise the setting quite well. The sun is out but it doesn’t provide any warmth, it’s crisp and dry and chilling. It should be a relaxing Sunday drive (cruising implies they’ve got nowhere particular to be, just driving around to pass the time) but something has got the speaker’s hackles up, a pervading feeling of wrongness that emanates from her surroundings. This kind of small town is supposed to represent wholesomeness, family, community, and belonging – but the speaker feels the opposite. To her the town is alienating and even hostile. She uses words such as offends and rebuke (meaning she’s being ‘scolded’ or ‘told off’) to make it clear that she feels like an outsider.

The way Atwood describes the town makes it seem planned so rigidly and laid out so inflexibly, that it actually feels quite oppressive, transforming her casual weekend outing into a tour through a prison camp. An overly oppressive sense of order and control is developed through a series of visual images that depict straight lines and precise, co-ordinated shapes: pedantic rows, planted sanitary trees, levelness of surface, straight swathe and the way the roofs of the town all display the same slant. There’s a sense that everything is smoothed flat, all the sharp, messy edges of life smoothed away, implied by words such as levelness, rows and straight. Such rigid adherence to order and organisation psychically affects the speaker who intrudes into and disrupts the order of the town. Her family represent dis-order, symbolised by the dent in our car door. They are just a little too messy and, well… normal to fit in to such an artificially perfect place. The town not only antagonises the speaker, but also opposes the natural world: the grass is mown straight, the roofs angle themselves away from the hot sky; even the trees are purposefully planted to create the illusion of nature where none in fact exists. They are described as sanitary, an eerie sonic echo of sanities, as if the trees have been cleansed and sterilised and recruited onto the opposite side of a war against nature, which is too wild, free, and unpredictable for the City Planners to stomach. The word sanities is actually used ironically; ‘sanity’ is the opposite of insane and means ‘not crazy’ – conversely, the poem develops the theme that a too-fixed and overly pedantic obsession with rationality is its own kind of madness.

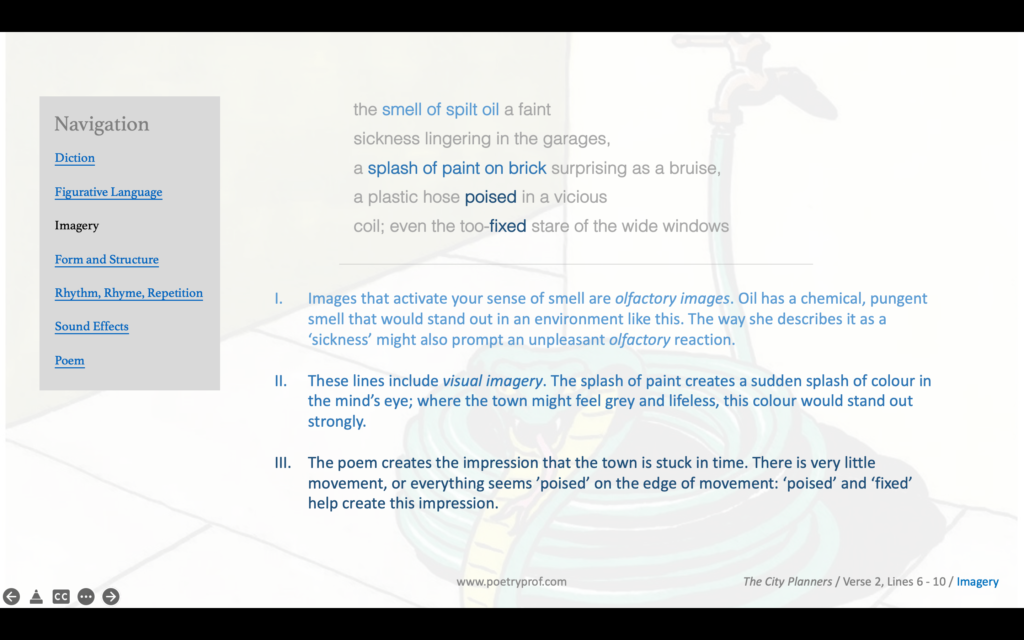

The feeling of lifelessness in what should be a thriving town is enhanced when you realise, somewhere towards the end of the second verse, that there’s no people anywhere. The town is empty – but it’s an uncanny, B-movie emptiness, as if everybody is attending the same cult meeting, or have been mysteriously evacuated, or are purposely hiding themselves away for some sinister reason. To draw attention to this strange lack of flesh-and-blood inhabitants, Atwood uses personification so the town seem like it’s running itself; the power mower whines and is cutting a straight swathe through a perfectly manicured lawn, but nobody is described pushing it along. The driveways sidestep, the roofs avoid the sky, the trees assert and rebuke and the poor, over-managed grass feels discouraged. There seems to be a latent threat of violence hanging in the air and frequently Atwood uses diction that suggests hostility or threat: shouting, shatter, cutting, bruise, poised, vicious. At one point she describes the sound of a lawn mower as a whine, an onomatopoeia of the sound an animal makes when it’s afraid or in distress. The feeling is very unsettling. All this builds to the uncomfortable too-fixed stare of the wide windows, as if the buildings – or unseen figures lurking within – are watching her threateningly, judgementally.

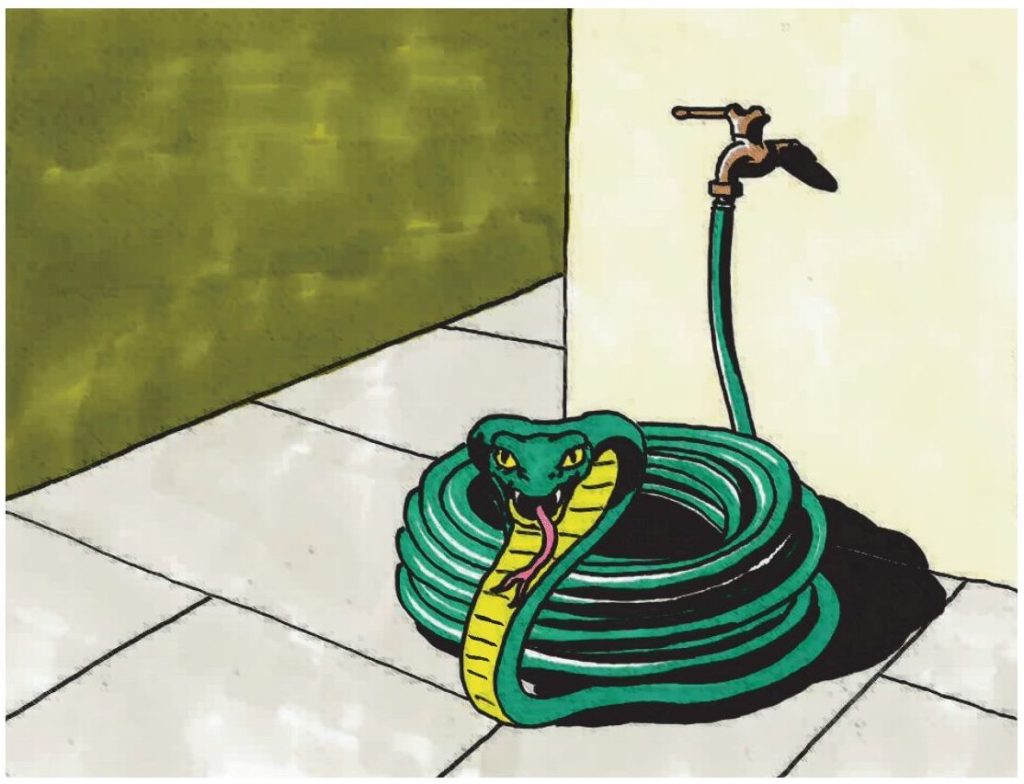

As being in the town is an unpleasant and even intimidating experience, Atwood arranges patterns of sound to help transmit this feeling to her readers. She frequently employs hard consonant sounds from every possible category: plosive P and B, dental D and T, and hard guttural C and K sounds. The poem opens with one of these gutturals that immediately undermines the relaxing connotations of cruising; what should be an easy afternoon’s drive is fraught with tension as they explore the hostile, deserted streets. Such hard sounds imply the threat of violence, also suggested through simile when a splash of brightly coloured paint marks the monotony of a blank brick wall like a bruise. Atwood foregrounds these sounds using alliteration (where words begin with the same letter, for instance, pedantic/planted… dent in our car door… plastic hose poised…) and consonance which repeats letters anywhere in a word: cutting a straight swathe in the discouraged grass. She presses hard consonants together so they clash unpleasantly: a splash of paint on brick surprising as a bruise compresses an impressive number of plosive sounds into a single line, and rebuke to the dent in our car door releases a cacophony of noises that jangles in the ear (cacophony is the clashing together of consonant sounds that do not blend or harmonise). Underneath everything hisses a sharp sibilance, insinuating itself into almost every line of the first two verses like a snake in the grass: Cruising these residential Sunday streets in dry August sunlight and sanitary trees assert levelness of surface are two lines that demonstrate the effectiveness of this sound, symbolically associated with snakes and therefore – thanks to the biblical story of a snake tempting Adam and Eve’s fall from paradise – evil, suggesting the underlying ‘wrongness’ of the town. At one moment she even describes a plastic hose poised in a vicious coil as if it really is a poisonous snake lying in wait for an unsuspecting intruder.

The madness and futility of trying to impose such absolute order so inflexibly on the world is revealed through certain things the writer sees at the end of verse two. No matter how completely the City Planners try to erase anything that doesn’t conform to their idea of a perfect town, life is inherently messy, accidents happen all the time, and people’s spontaneous desires can’t be permanently repressed. Someone has spilt oil somewhere, there’s a random splash of paint on a wall, and a hose has been left lying around carelessly. All three of these instances symbolise the futility of the City Planner’s efforts to erase spontaneity, chaos and disorder from human lives. In this section of the poem, we start to realise that these certain things are not threatening to the speaker, although she certainly feels wary, but threatening to the minds behind the town’s design. From their point of view tiny deviations such as the smell of spilt oil are like a sickness, as if the town can be metaphorically ‘infected’ by carelessness, and no amount of frantic scrubbing can fully ‘cure’ the illness of clumsiness. Similarly, the splash of paint becomes a bruise turning an innocuous slip of the brush into an act of vandalism; the hose is poised on the edge of a vicious attack. To anyone inured to such a bland, grey vision of the world, these unexpected twists and splashes of colour must be surprising and shocking. But for the speaker, and for us, they reveal glimpses of the truth hidden behind the City Planner’s brutalist designs – they can’t keep the real world, with all the inherent messiness and chaos of life, walled up completely.

At the end of verse two, the speaker’s attention is transfixed by the too-fixed stare of the wide windows – and the poem creates the effect of her being slowly drawn into the smoky glass. Once she’s penetrated beneath the illusion of solidity the City Planners have created, she’s granted momentary access to a vision of the real, living landscape that’s buried beneath the City Planner’s vulgar, dystopian town. I love what happens to the poem’s form when she begins to experience this vision. It’s like we’re watching that Twilight Zone episode again, and the camera zooms in on the actor’s face while the background remains bizarrely still. The way the vision hypnotically unfolds in the speaker’s mind is evoked through enjambment linking verse three to verse two seamlessly. There’s no full stop at the end of the second verse so the poem just keeps going, crossing over the intervening white space as if crossing a threshold between ‘now’ and what will be in the future. The third verse takes all the town’s straight lines and skews them, folding them up and screwing up the City Planners’ orderly blueprints with the phrase behind or under. Where the poem is frequently interrupted and truncated in verses one and two, as if lines of poetry are roads in the town that need controlling (caesura, deliberate breaks in lines of poetry, made with colons, semi-colons and short lines leaving plenty of blank space create this impression), verses three and four are fluid, with barely any interruption to the flow of words. Having felt so confined, suddenly the prison walls melt away as the world shifts into a new, post-human epoch.

As we’re propelled forward in time, we see cracks in the plaster that break the City Planner’s spell and pretty soon the whole town is revealed to be a film-set sham hiding the real world behind its thin, pretend veneer. Where the fake, plastic town asserts levelness and order, we now see the natural world ‘reassert’ its own chaos. The cracks of entropy and decay are processes inherent to life that can be temporarily disguised, but not reversed or eradicated. Projecting into the far future, the speaker imagines a time when the houses… will slide obliquely into the clay seas, obliquely being a word that pointedly contrasts with the City Planners’ rigid adherence to straightness and order above all else. Where verbs were either absent, muted (like planted) or negated in the opening verse (no shouting here, or shatter of glass) now the poem presents a vivid image of powerful movement as the entire city slides into the ground. While the City Planners think their constructions and monuments are permanent, Atwood’s speaker suddenly presents them as flimsy and temporary, implied through the word capsized, as if the houses in the town are metaphorical boats; instead of standing on firm foundations, they merely float for a while before the natural and inevitable shift in the world’s climate drags them under a topographical tidal wave. She remembers that the earth is not immobile, but in constant motion – even the mountains grow and shrink over the centuries. Of course, these processes occur imperceptibly slowly, so the phrase gradual as glaciers reminds us that evolution is measured in geological time, over thousands and millions of years. While nobody notices, change is nevertheless inevitable and irresistible; the speaker is certainly gripped by the truth of her vision, as implied by the modal verb will, conveying a strong degree of certainty as to what is going to happen. Enjambment again comes to the fore in this middle section of the poem, crossing the white space between verses as if crossing eons of time and letting lines flow one into the other in mimicry of the houses slipping slowly-but-surely into the ground. Opposing sounds reinforce the conflict between human and natural worlds, the former accompanied by a weak sounding N (now nobody notices), the latter by powerful, guttural alliteration (capsized, clay, gradual, glaciers) throughout this verse.

Finally, in verse five, Atwood brings the titular City Planners into the poem. These people symbolise forces of urbanisation which, by definition, encroach on our remaining natural spaces. They are authority figures who control our cities and towns, urban planners who make decisions about our built environments, determining where and how we can live. However, in a clever twist on the name Planners, which implies organisation, forethought, and an ability to work together as a team, they are instead depicted as disorganised, frantic, and incoherent. They are lost, scattered over unsurveyed territories (a phrase implying the natural world is just a development opportunity to them) and instead of following a proper plan, they are guessing directions. They are concealed from each other, every individual marooned inside his or her own private blizzard with no way of seeing beyond the ends of their own noses, let alone communicating and coordinating with others in their team. Atwood’s decision to write her poem in free verse really pays off here, as the absence of any underlying rhythm or rhyme scheme reflects the total lack of coherence in their designs. They are constantly described using diction from the lexical field of ‘mania’ (hysteria, insane, panic, madness) leaving us in no doubt that, in the opinion of the poet, these people are motivated as much by their own insecurities and fears as they are by lust for control. She uses metaphor to describe their faces in a way that renames them political conspirators; Atwood believes these people have no real interest in landscaping, city planning or design, rather they manipulate our physical environments as a way of exerting control over our lives and staving off their existential fear of destruction as the world spins inevitably into the future and massive climate change exposes the insignificance of our short-sighted human civilisations.

The ultimate futility of the City Planners’ war against nature is highlighted through a series of impossible contrasts and paradoxical images: transitory lines are described as rigid; a solid wall vanishes into thin air; order contrasts with panic; bland madness is an oxymoron (a kind of juxtaposition where contrasting words are paired improbably together). Despite their efforts to build permanently over the natural landscape, snow and ice become the defining motifs (a motif is a symbol that keeps recurring in a text) of the last half of the poem, as if the world has been plunged into a new ice age: glaciers, blizzard, white vanishing air, madness of snows. These powerful elemental forces engulf the City Planners so that the speaker sees them only from a distance, a perspective that makes them appear small and powerless, their frantic attempts to continue their mad work under these conditions just looks pathetic. As the illusion of authority is stripped from her – and our – eyes, we are all freed to question the right of the City Planners to dictate how our present-day world should look and feel.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Moment by Margaret Atwood

In this lovely poem by the same writer, a woman feels close to nature – so close she feels she owns parts of it. But then the natural world begins to withdraw, and she is forced to reassess her relationship to the natural world.

- The Second Coming by William Butler Yeats

If you enjoy post-apocalyptic poetry, you might like this famous poem by Yeats, who imagines the destruction of the world by a terrifying beast representing all the forces of nature. This poem is where the famous line ‘Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold’ comes from.

- The Planners by Boey Kim Chung

A perfect companion for Atwood’s poem, Boey Kim Chung writes about the expansion of his home, Singapore, in a similar way. In this poem, City Planners are like dentists, anaesthetising you against any reaction to the pain they cause as they plan, demolish, rebuild, expand, in a never-ending cycle of relentless urbanisation.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The City Planners at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. So that you can see for yourself how effective our resources are, for now, this bundle is free in the store.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining figurative imagery in poetry.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Margaret Atwood’s poem? What did you feel when you first followed the speaker through the sinister suburb? Do you think it’s a dystopian poem as well? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.