Stevie Smith wonders whether mankind is truly alone in the world

“Her song is worth hearing”

Caitlin Timball, writing for Poetry Foundation

Stevie Smith was a very enigmatic poet. Her poem Touch and Go wrestles with ‘big’ questions in a deceptively simple way. Over the course of seven quick verses, Smith examines the evolution of mankind and wonders whether we (as a species) have been abandoned by God and are now lost in a cruel and indifferent world. The poem takes a cosmic viewpoint on mankind as we separate ourselves from animals, striving to become ‘distinguished’ in some way. Smith asks us to consider our relationship with nature in an interesting way; we seem to be the only animals not content with our lot, who strive against base instincts and try to ‘better’ ourselves, putting ourselves at odds with the natural order of things and making enemies of powerful, natural beings. There are parallels with the fall from paradise here, which was brought about through the search for forbidden knowledge, and is a theme that Smith has pursued in other poems, such as Away, Melancholy (which I’ve written about here). The poem ends on an ambiguous note, asking whether we should leave religion behind and continue on by ourselves, or whether we should persevere with prayers that never seem to get answered:

Man is coming out of the mountains

But his tail is caught in the pass.

Why does he not free himself

Is he not an ass?

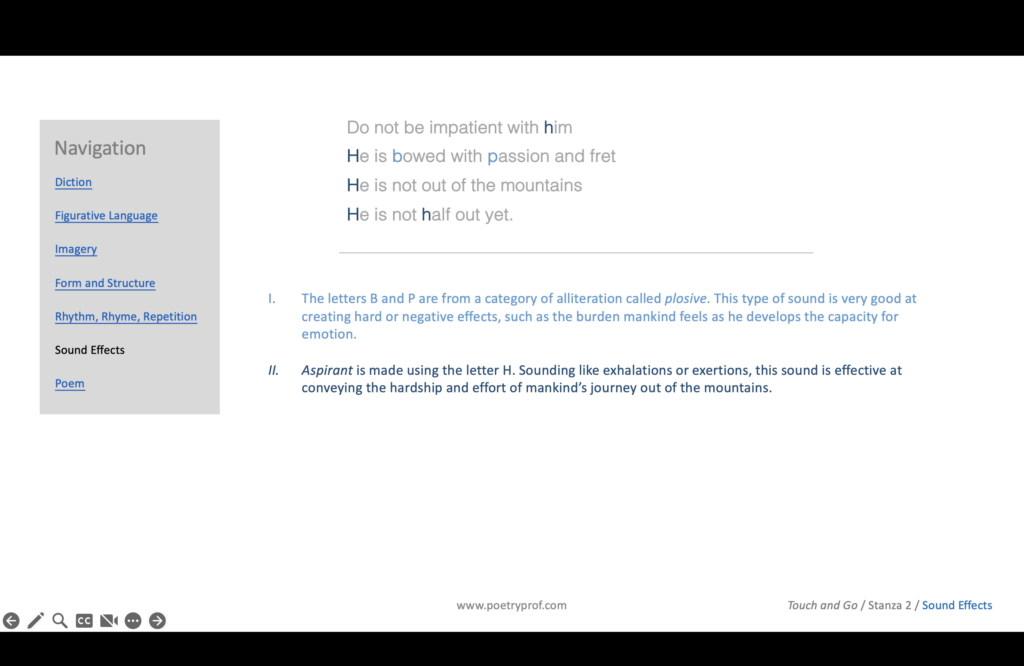

Do not be impatient with him

He is bowed with passion and fret

He is not out of the mountains

He is not half out yet.

Look at his sorrowful eyes

His torn cheeks, his brow

He lies with his head in the dust.

Is there no one to help him now?

No, there is no one to help him

Let him get on with it

Cry the ancient enemies of man

As they cough and spit.

The enemies of man are like trees

They stand with the sun in the branches

Is there no one to help my creature

Where he languishes?

Ah, the delicate creature

He lies with his head in the rubble

Pray that the moment pass

And the trouble.

Look, he moves, that is more than a prayer,

But he is so slow

Will he come out of the mountains?

It is touch and go.

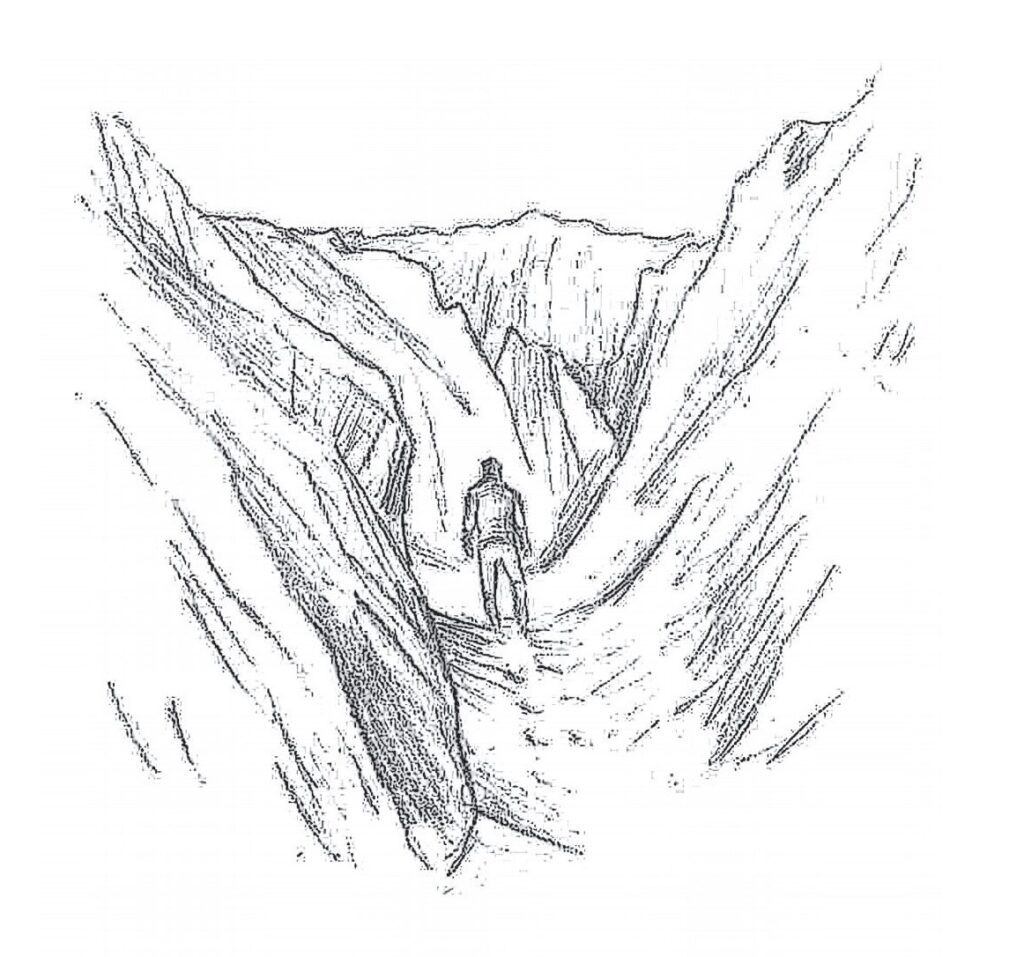

Smith’s conceit (a conceit is an extended metaphor that runs through the whole of a text, in this case, the poem Touch and Go) is to imagine the whole of mankind embodied in a semi-evolved creature coming out of the mountains which are the home of creatures, animals, monsters of nature. As mankind leaves this realm, his tail gets caught in the pass, a symbolic moment that is a kind of ‘fork in the road’ for humanity’s evolution. Will he be able to shed his bestial nature and evolve into something more distinguished? Having separated himself from nature, can he succeed on this journey alone? This is the driving question of the poem and one that the speaker is not able to answer definitively. Throughout the poem Smith interchangeably refers to humanity as man and creature, at one point using the phrase delicate creature to encapsulate the liminal, semi-evolved state of mankind by pushing the more brutish creature against the refined word delicate like an oxymoron. Right at the start she asks: why does he not free himself is he not an ass? Smith was extremely fond of wordplay and this is a perfect example of the way she plays on the double-meaning of words. An ass is a donkey with long ears and tail – but the word is also slang for a foolish or stupid person. Written in simple monosyllabic language and using childlike rhymes (pass/ass, fret/yet, and so on) the poem imagines man as a simple, childlike creature. A donkey would simply use brute force to pull his tail clear, but mankind, rid of basic survival instincts and clumsy enough to get his tail caught, seems unable to move beyond this moment of crisis.

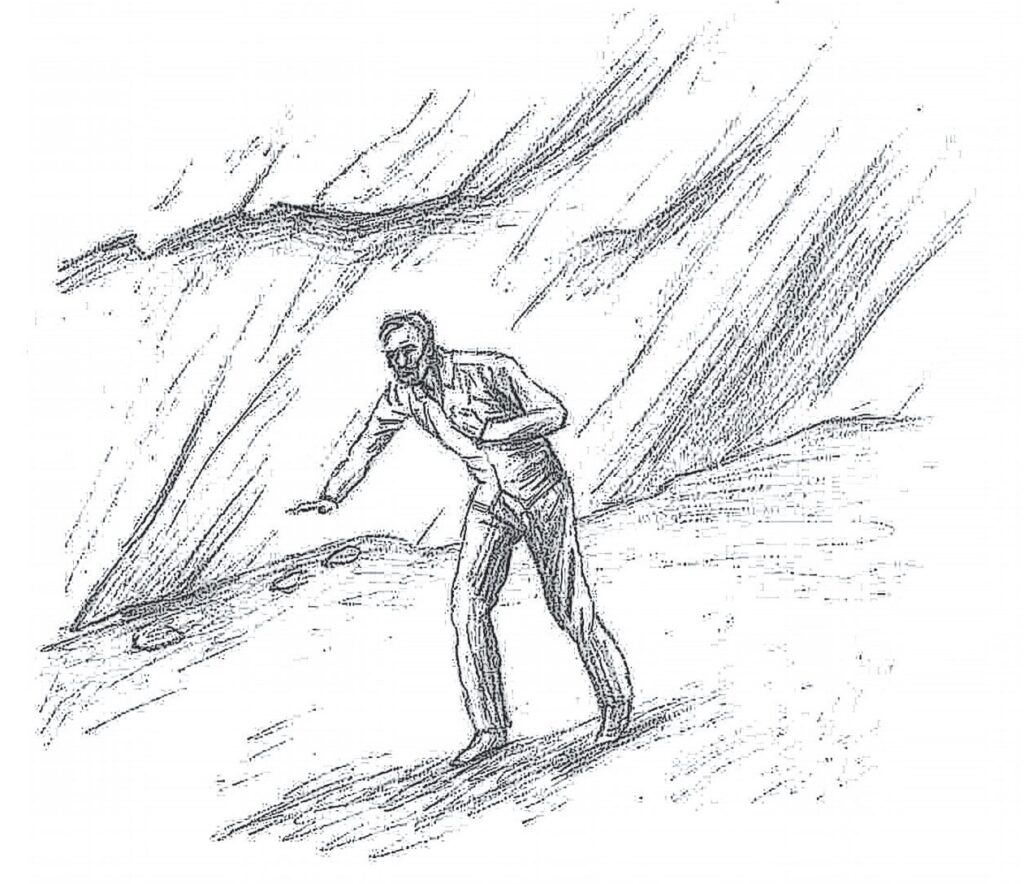

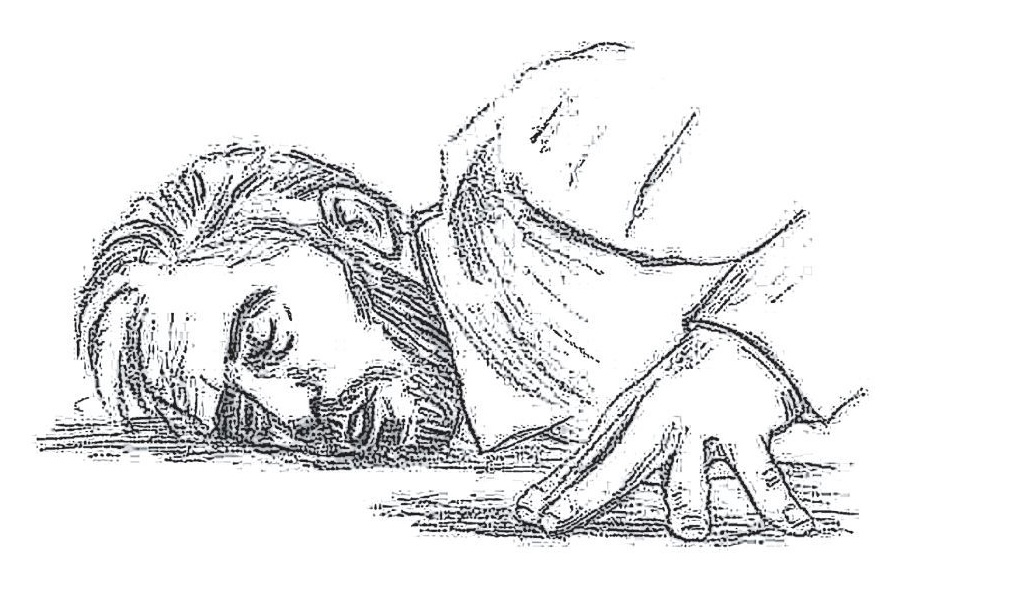

Raised in a religious household as an Anglican, nevertheless Smith wrestled with religious faith throughout her life, and you can feel the tension between her and a God who may or may not be listening. Like a child with an arm stuck in a sliding door, mankind needs a helping hand from a caring parent to pull free. Notably, at the start of verse two, Smith appeals directly to a higher power not to abandon mankind in his hour of need. She creates a strong, imperative tone by placing the verb at the start of the line, imploring – almost demanding – Do not be impatient with him. Her worry is that mankind is developing too slowly or too imperfectly for God to put up with anymore, and he will abandon his children at this crucial make-or-break moment. The second line of this verse uses emotive diction to paint a picture of mankind’s suffering, such as in the line he lies with his head in the dust. Images throughout the poem are of weakness, frailty and exhaustion as mankind stumbles, falls, and lies hurt. You may recognise allusions to Jesus climbing to the site of his own crucifixion (his torn cheeks, his brow) in verse three, during which he was beaten, fell, and bled on the ground. Smith is not-so-subtly reminding God that we are all his children, all suffering, and all in need of help. At this point, she uses aspirant alliteration (the repetition of the letter H beginning the words his, his, he, head, help) to create auditory imagery that tugs at the heartstrings. Made by expelling air like exhalation, aspirant is excellent at conveying the sense of effort and exhaustion mankind displays at this moment of crisis. Surely God cannot stand back while mankind – his children – are in such dire need of help and guidance.

In this way, the poem becomes an exploration of faith, perhaps revealing Smith’s own doubts about the relevance of religion in the modern world. At mankind’s lowest moment, exhausted, abandoned, weighed down by pain and suffering, with his head in the rubble, his last resort is to pray, a word that appears for the first time in stanza six. Again, Smith uses the imperative tense, placing this word at the start of a line of poetry to give it the force of a command: pray that the moment pass. Other moments in the poem that repeat a similar call for help can be interpreted as prayer also. The final stanza contains an element of hope as man moves feebly forward, continuing to evolve, whether God is helping us or not. More than a prayer suggests there is some kind of force driving us on: Evolutionary forces? An innate desire to better ourselves? The sequence of the poem leaves open the possibility that man’s strength to go on is an intercession in itself. I’m reminded of Garth Brooks’ classic lyric: just because he doesn’t answer doesn’t mean he don’t care. Perhaps the very fact of man’s ability to keep going is proof that someone upstairs is keeping an eye on us? Whatever you think about this, Smith refuses to give us an easy conclusion. At times it seems like we will not make it, and the poem ends by confirming this doubt: on asking Will he come out of the mountains, she answers: it is touch and go, a phrase meaning the outcome is uncertain or impossible to predict. The questions the poem raises are not answered.

As well as wrestling with her own religious ambivalence, Smith’s poem explores other philosophical questions concerning man’s place in the pantheon of existence. Go back to verse two and consider the image of man being bowed with passion and fret. Smith’s idea is that, as we separate from animals, we evolve higher, more distinguished qualities such as emotion for one another. However, this unique capacity, if we live in a godless world, becomes a burden to carry. The word bowed suggests Smith’s creature is weighed down by worry and anxiety (fret). This kind of negative lexical field continues through the whole poem. After fret comes: sorrowful, torn, languishes, trouble, all words painting man as a weak and fragile creature suffering greatly. The image of lying exhausted on the ground is repeated twice, once in verse three and again in verse six: he lies with his head in the rubble. The evolutionary journey of mankind, leaving the animal realm and coming into his emotional fullness, is long and slow; at one point an alliterative so slow draws out the excruciating pace. The poem’s tension never fully resolves: if God really has abandoned his children, is mankind strong enough to keep going by himself?

Nevertheless, it’s clear that mankind is losing his animal nature, none more-so than in the contrast between mankind and his ancient enemies. These ambiguous beings make a dramatic appearance in stanza four, straight after Smith asks Is there no one to help him now? Like demons or devils they say, let him get on with it, perhaps trying to trick mankind into abandoning their faith and going on alone. In fact, this cackling cry is the one and only time we hear an answer to Smith’s calls for help. Indeed, trickery seems to be their game; for a couple of lines at the start of stanza four their voices take over from the poem’s speaker, leaving the reader a little disorientated. Stanza four has a harsh, unforgiving tone, Smith using hard consonance (let, get, it, cry, cough, spit) to give us a sense of their bile-filled, venomous voices, and the jagged hatred they direct at humankind. Where man is an emotional being, the enemies of man are empty of pity and emotion, except for this intense malice; they cough and spit repulsively, as if they are corrupted by their scorn for this wayward half-creature. Like fallen angels, perhaps, their outward appearance contrasts with their natures; they appear as magnificent beings, resembling trees with the sun in their branches blazing like a halo of light while we languish weakly in the dirt (the word languishes has a double meaning; to become weaker and feebler, or to be forced to stay in an unpleasant situation; both meanings suit this moment). These descriptions are interwoven with plenty of sibilance (stand in the sun) which adds to the beauty of the descriptions. But, through biblical associations with the snake who whispered tempting words to Adam and Eve, sibilance can be used to convey evil or sinister feelings as well. Maybe the ancient enemies of man have forked tongues that whisper poison in man’s ear, making them symbolic personifications of doubt and lost faith. In a world of suffering where calls for help are met with silence, why should we continue to pray to a God who’s not there?

Writing in 1950, with the echoes of World War Two reverberating in her ears, it’s understandable that Smith may have been wrestling with questions of God’s existence. Her depiction of man with his head in the rubble alludes to the destruction wrought by modern weapons on a global scale, and a sense of hopelessness pervades the poem. Set in a barren mountain pass, Smith creates an indifferent world where silence is the only answer to pleas for help. Has God, appalled by the actions of his children, abandoned us in our time of need? Or, tempted by malicious whispers, have we allowed ourselves to be persuaded that we’re alone in the world? Beset by doubt, can we go on? The answer is touch and go.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Away, Melancholy by Stevie Smith

A very similar poem to Touch and Go. Smith imagines a world of hardship and suffering where primitive humans erect stone edifices in prayer and to find meaning in a world that would soon forget about them.

- The Lamb by William Blake

Smith has been compared to Blake in style. Both poets used simple, almost childlike rhymes and, at times, both explored similar themes, such as in the example of this poem. A little lamb (or child) who wonders at the miracle of creation is told about God, ‘who made thee’.

- In Praise of Creation by Elizabeth Jennings

Another poet who wrestled with faith and doubt is Elizabeth Jennings. In this poem, despite his seeming absence from the world, Jennings finds solace in the idea that creation itself is evidence enough of God’s existence.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Touch and Go at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining how figurative imagery works in the poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Stevie Smith’s poem? What do you make of her pitiable man-creature? Do you think the poem ends on a note of hope or hopelessness? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.